- Grand Bahama in 1887 from L. D. Powle The Land of the Pink Pearl or Recollections of Life in the Bahamas.

- Grand Bahama in 1891 from Stark's History and Guide to the Bahama Islands.

- Grand Bahama in 1917 from Amelia Defries In a Forgotten Colony

- Grand Bahama in 1924 from The Tribune Handbook

- Grand Bahama in 1926 from Mary Mosley The Bahamas Handbook.

- Grand Bahama in 1931 from Nassau and the Treasure Islands of the Bahamas

- Grand Bahama in 1934 from Maj. H. M. Bell Bahamas: Isles of June

- The Bahamas in 1964 from Benedict Thielen The Bahamas-Golden Archipelago

- rand Bahama in 1967 Moral Panic, Gambling. and the Good Life

Ten, Ten The Bible Ten : Obeah in the Bahamas

Dr. Timothy McCartney

Nassau: Timpaul Publishing (1976)

SECTION II

ASPECTS OF SLAVERY (Continued)

and happy. On all hands too I had heard complaints of their uppishness, laziness and general good-for-nothingness. One day I observed to a high official that the independent assembly was a simple absurdity, and that the little place ought to be made a Crown colony at once. Said he, As a Government official I should be very glad to see it made a Crown colony, but it would never do; the negroes would be as well off as they are in the rest of the West Indies. . .

"The 'truck system.' called by the Americans 'the store order system,' is, as every one knows, the substitution of payment in kind for payment in cash. It is undeniable that in some cases, this system may work well, and I have myself seen it acted upon with very good results in one of the smaller islands in the Bahamas, where are salt ponds. For many years the price of salt has been so low that it has been next to impossible to ship a cargo at a profit, and most of the salt islands are at present without trade. In this particular island, when a vessel comes in, the principal salt-owners take their net, go hauling, and divide the take among the men who carry the salt on board. In this way they shipped 38,000 bushels of salt at a profit in less than five months. All the island had benefited, for the weight of fish given the man far exceeds in value the amount they would have received had they been paid for their labour in cash. But this is a small island, containing only some three or four hundred inhabitants, where a patriarchal state of things exists.

"Very different is the working of the truck system between the Nassau merchant and the unhappy negro, whom, by means of it, he grinds down and oppresses for years and years. The principal industries of the colony are the sponge and turtle fisheries, and the cultivation of pineapples. Through the truck system the benefit derived from these sources by the working man is not only reduced to minimum, but he is virtually kept in bondage to his employer. The sponger and turtler are the greatest sufferers because they are kept under seaman's articles all the time.

"Let us follow the career of one of these unfortunates from its commencement. He applies to the owner of a craft engaged in the sponge or turtle fisheries, generally in the two combined, to go on a fishing voyage. He is not to be paid by wages, but to receive a share of the profits of the take, thus being theoretically in partnership with the owner. At once comes into play the infernal machine, which grinds him down and keeps him a slave for years and years—often for life. His employer invariably keeps, or is in private partnership with some one else who keeps, a store, which exists principally for the purpose of robbing the employee, and is stocked with offscourings of the American markets —rubbish, unsaleable anywhere else. As soon as a man engages he has to sign seaman's articles, which render him liable to be sent to board his vessel at any time by order of a magistrate. He is then invited, and practically forced, to take an advance upon his anticipated share of profits.

"Under the auspices of Governor Blake a Bill was passed in the House of Assembly, in the Session of 1885, limiting these advances to ten shillings; but any merit there was in the Bill was destroyed by an amendment, permitting them to be made 'in kind or in cash'. Besides, all through the time I was in the Bahamas this law virtually remained a dead-letter, as I do not hesitate to affirm .—has been the case in the colony with every law passed for the benefit of the coloured race, that at all militates against the interests of the native whites.

"These advances, I need hardly say, are generally made in kind, consisting of flour, sugar, tobacco, articles of clothing, or some other portion of the rubbish that constitutes the employer's stock-in-trade. Probably the fisherman does not want the goods, or, at any rate, he wants money more to leave with his family; and in order to get it he sells the goods at about half

37

the price at which they are charged to him. I was about to say half their value, but this would be grossly incorrect, for the goods are usually worth next to nothing, whereas they are charged to the fisherman at a price which would be dear for a first-rate-article. . . .

"Preliminaries settled, the fisherman starts on his sponging or turtling voyage, and remains away from six to twelve weeks, when he returns with his cargo of sponges. These he cannot by law take anywhere, except to Nassau, where they have to be sold in Sponge Exchange by a system of tender.

"Of ever anything analogous to the Jamaica emerite should cause Great Britain to send a Royal Commission out to inquire into the condition of this unhappy colony, the truth about these sales may come out. Personally, I hold the strongest opinion that they are fraudulent. The seller is a Nassau merchant, the buyer—usually the agent of a New York firm—is also a Nassau merchant; and that the two agree together and arrange a bogus sale, by means of which they rob the unhappy fisherman, I am convinced. . .

"Just before my last circuit, Sam Gowan, one of my boys, had been away for five weeks in charge of a sponging schooner. They had brought back 900 strings of sponges called beads. These beads—taking large and small together—averaged, Gowan told me, nine sponges each, or 8,100 in all. He and his crew had not only taken his cargo of sponges, but had cleaned and dried them as well—a very troublesome process. The whole cargo fetched, in the Sponge Exchange, 11 pounds sterling, or less than a halfpenny a sponge all around. Yet many of these sponges would fetch five or six shillings in a shop in London, whilst the smallest would not be likely to fetch less than 6d. Here is a case in point.

"Besides, if these sales be not fraudulent, perhaps the Nassau merchant can explain how it happens that on the Florida Coast, under exactly the same conditions as to water and the quality of the sponge, the fisherman can earn twice and three times as much as those who fish in Bahamian waters.

"The sale over, the amount realized is declared, and owner and fisherman proceed to share. The fisherman is already liable to the owner for his original advance, and his share of the expense of provisioning the vessel. Nine times out of ten the farmer makes out that there has been a loss and the fisherman is in debt to him, or, at any rate, that there is nothing to divide. . .

"The condition of the labourer in the pineapple fields, almost the only fruit of the soil that is at present exported to any extent, is only so far better than that of the fisherman in that, as his work has to be done on land not by sea, he cannot, like his fellow-sufferer, be kept continually under seaman's articles, but, except in one or two places where the people have been roused by a leading spirit, he is kept in a perpetual state of debt through the truck system.

"In some cases the pineapple cultivator is a peasant proprietor, in others he cultivates for the owner of the soil upon share. In both cases the Nassau merchant appears on the scene. 'Like flowers that bloom in the spring,' he appears with the pineapple season and disappears with it; save that instead of a flower he is a upas-tree, blasting and withering wherever he sets his accursed foot. Sometimes he appears in the character of owner of the soil, sometimes in that of agent. In the former case he contracts in his own behalf with the captains of the vessels that call for pineapples; in the latter on behalf of the cultivators. In both cases the coloured peasantry have to suffer, for they are in his hands. He receives cash for the pineapples from the captains and pays them with his worthless goods. Where he is an agent he often has a two fold opportunity for robbery, of which he generally—I do not say invariably—avails himself, by

38

The sponge fleet, i.e. the large

vessels engaged in the sponging trade, usually consisted of six hundred

(600) vessels - schooners and sloops built in local shipyards. These vessels

had an average life of sixteen to twenty years, and carried up to five

dinghies which were used for gathering the sponge. Each vessel had a small

cabin for sleeping; cooking was done on deck. A typical crew consisted

of ten men and a cook; voyages lasted five to eight weeks depending on

the catch. The Great Bahama Bank, an enormous shoal on the west side of

Andros nicknamed The Mud, and one of the great sponge beds of the world,

was the most popular sponge fishing bed. Before a vessel went out on a

sponge fishing voyage, the outfitter furnished the consumable goods and

stores. This was done entirely on a credit basis and he was not reimbursed

until the catch was marketed at the end of the voyage. The goods were

booked at cost, plus a considerable margin of profit. These "personal

advances” to members of the crew, often including food for their

families, were recovered at high rates of interest, making it almost impossible

for the fisherman to make any economic advance. Often he was left in debt.

The outfitters, however, felt justified in their high rates, as they themselves

took considerable risks. Their vessels were not insured and there were

the risks of bad weather which affected the size of the catch, mismanagement

and unscrupulous behaviour on the part of the crew, theft from the kraals,

and damage to the catch during transit from Nassau.

39

accepting a douceur from the captain to persuade his clients to sell at a less price than the captain has come prepared to give.

''In one case that happened within my own knowledge, one of these light-fingered gentry accepted—or said he had accepted—bills for the amount due for pineapples from an American firm, which bills were never met, and several old people died of starvation in consequence. When I arrived at the settlement in question, the haggard looks of the poor folk told their piteous story far more eloquently than the flood of words in which they poured it out to me. This conduct was absolutely inexcusable, for plenty of vessels call every year for pineapples, and there is never the slightest necessity to ship a cargo without cash down, and I haw little doubt the person in question was bribed to behave as he did.

"The cultivator thus gets a low price for his pines, and gets it in goods which, as in the case of 'the fisherman, are invoiced to him at the price of real good stuff, but are of so poor a quality that they will not go far. The result is that long before the next pineapple season, he is threatened with starvation, and mortgages his next year's crop to the Nassau merchant in return for an advance, and the relations of master and slave are established.

"I am bound In common fairness to add that the native white Bahamian is not alone guilty, for when a black man gets into the position of an employer of labour he is usually quite as bad, but when it is but natural that he should imitate what he has been brought up to look upon as the superior race.

"In fact there are very few among the working classes of the Bahamas who know what it is to handle cash at all, except domestic servants and skilled work-people; and we have already seen that in the Out-Islands even ship-builders do not always get paid in cash. Still as a general rule these two classes do get it.

"Whilst on the subject of slavery, it may be as well to mention a case that, as far as I know, has never been brought to the notice of the British public, but which certainly ought to be known.

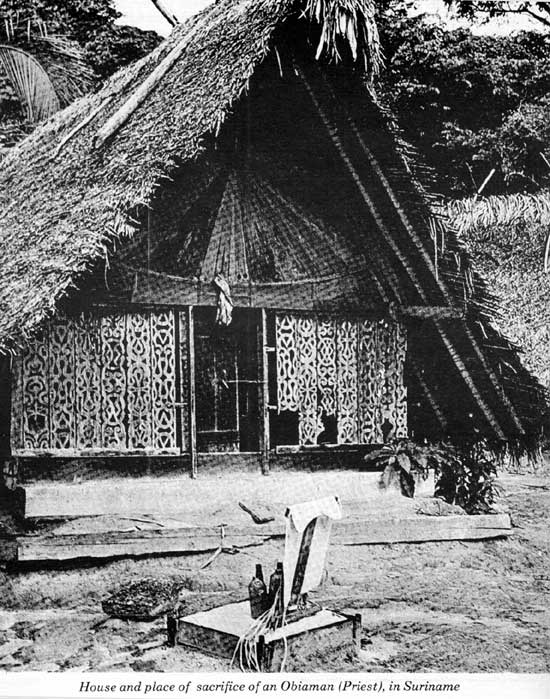

"About eighteen years ago, one of the Nassau merchants acted as agent for the Dutch government, to hire labourers to go to Surinam on a contract of service analogous to that under which coolies are at present hired in many parts of the West Indies. A number of coloured Bahamians engaged themselves, and were shipped off. Only one has ever returned. He had the courage to put to sea in an open boat, and the luck to meet with a passing vessel which carried him to England, whence he was sent back to Nassau. The tale he tells is sad to the last degree. The men had no sooner landed in Surinam than they were told they were slaves, put in irons, and subjected to all sorts of hardships. Some pined away and died, one poor fellow—who had been a school master at home—cut his throat, unable to endure the shame and degradation of his position. Of the fate of a good many, the survivor can give no information, but I have heard my colleague express the opinion that some of them may be still alive. It is strange that I have forgotten the name of the poor fellow who survived, though I have often seen and talked to him, and he is as well known to everybody in Nassau as the streets of the city. John Stefney is now slightly deranged from the effects of his sufferings, but has had lucid intervals, during which he can give an intelligent account of what he knows. To the credit of the people of Nassau be it said, he is kindly treated by everybody, and is commonly spoken of as 'the poor man who was sold for a slave,' To the best of my knowledge and belief no communication has ever been received by the friends and relatives of any other individual who started on that ill-fated expedition.

40

"To the best of my belief also, no action has ever been taken by the Imperial Government in this matter. Yet every one of these men was a free-born British subject, as much entitled to the protection of our flag as the first nobleman in the land. Is it even now too late for something to be done for our fellow-subjects who may at this moment be languishing in slavery?

"Shortly after my first circuit I had many conversations with Governor Blake upon the condition of the coloured race in the colony, and I am convinced that no man was ever more sincerely anxious to benefit then he was, at that time.

"In many other speeches, besides the one cited by the author of the articles in "The Freeman,"* he pointed out to the people that as long as the Truck system existed, they were in slavery, as every man must be who is in debt.

"Considering whom he was addressing, 'slave' and 'slavery' were dangerous words to use. "To the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of those who were emancipated in 1837, these words represent something tangible that they can understand and realize. The rest of the sentence, explaining the sense in which the words were used, would express nothing to their minds. And so it turned out, for if I have had it said to me once, I have had it said fifty times, 'De gubner say we slaves… '

"A case brought to my notice by Professor Brooks of Baltimore I hardly know whether to class under the head of the 'truck system' or to call by an uglier name. The professor being engaged during the winter of 1886-7 in a scientific examination of the sea-water, hired a coloured workman through the agency of a white Nassau merchant. The merchant was to pay the man, who was to receive —1 pound a week. Subsequently Professor Brooks discovered that the merchant was paying the man 6s. a week and pocketing 14s.! The professor immediately paid the man himself and the merchant threatened him with an action for damages.

"The merchant in question belongs to a powerful family, and is connected either by blood or marriage with whatever there is of influence or money in the town of Nassau. Incredible as it must appear, I have little doubt that had he brought an action against Professor Brooks in the Court of Common Pleas, he would have succeeded, as the judges would have been afraid to offend so influential a connection.

"And this story leads naturally on to the question whether justice is equally administered between black and white. Of course it will be alleged against me that I am unfairly prejudiced. Of that I am ready to take my chance, but I unhesitatingly assert that even handed justice between black and white is all but unknown in the Bahamas. Neither will it even become a general rule as long as a single judicial office remains in the hands of a native white. How can it be otherwise? All the native whites are connected with each other, and the higher officers are so badly paid that independence is all but an impossibility even where men are actuated by high motives. God forbid that I should deny that in Nassau, as elsewhere, there are many men and women with good instincts, but is not human nature the same all the world over? A man has a miserable salary and no retiring pension; perhaps he has family to support? He lives in a small place where he is connected with every one of the dominant race, a narrow-minded, over-bearing clique, who imagine themselves to be a species of untitled aristocracy; a sort of thirty tyrants of Athens; an Oligarchy irresponsible save to itself. All his hopes of any active assistance outside

*A popular Bahamian newspaper that published from 1886 to 1889.

41

42

his official salary, of any comfortable social intercourse, of an endurable existence in fact, depend upon his relations with the people! In heaven's name how can he do equal justice unless he be a man cast in an iron mould?

"The white natives are very fond of citing the case of the present Colonial Secretary, who thirty years ago suffered severely for doing equal justice between black and white. At that time he was police magistrate, and had to convict and fine his father-in-law for assaulting a black boatman. His father-in-law immediately turned him out of doors, and prosecuted him in every way for the rest of his life. Whilst sympathizing with him to the fullest extent, it must be evident that, after all, he had only kept the oath he took on taking office, a thing every British judge or magistrate is supposed to do so as a matter of course. The treatment he received at the hands of his father-in-law only shows what any member of the clique must expect, who dares to oppose the will of the rest, and how much moral courage a man requires to do his duty against such odds.

"The above is the only case the native whites ever cite on their side of the question. The cases on the other side are endless; I will instance a few that have happened quite of late years.

"Some little time ago a member of the clique was charged before the sitting magistrate with tying a black boy to a tree and beating him nearly to death. The doctor in charge of the asylum heard the child's shrieks, and had he not sent one of the asylum nurses over to interfere, it is extremely probably that the child would have been killed. For this offence the accused was fined 50s., which was thought a very severe punishment. Can any one doubt that if he had been a black man he would either have been sent to prison without the option of a fine or else committed for trial?

"Shortly after my arrival an instance occurred which showed me how impossible it was for one of these natives to do justice. My colleague was in charge of the Police Court, and I was standing by talking to him, when a girl name Rosa Poietier came in to apply for a summons against one of the principal men in Nassau and a member of the Executive Council, for assaulting her and turning her out of doors without paying her wages, her offence being that she insisted on wearing a piece of green ribbon, the badge at that time of those who supported Governor Blake. The girl's story may have been true or false, I cannot tell, but at any rate she was entitled to be heard. But my colleague sent her to the Civil Court to bring an action for wages, ignoring the charge of assault altogether! He did not dare do otherwise! Some time ago at Harbour Island, the second place in the Bahamas in importance, five coloured men, named Israel Lowe, John D. Lowe, David Tynes, William Alfred Johnson, and Joseph Whylly, determined to test the right of the authorities of the Methodist Church to prevent a coloured man from entering the chapel by the same door as a white man. With this view they walked quietly in at the white man's door and up the aisle. The service was discontinued until they were turned out, and prosecuted the next day before the resident justice who convicted them of brawling, and fined them 20s. each, with the alternative of imprisonment. And yet the men so treated had contributed both by money and manual labour to the construction of this chapel.

"Whilst I was sitting in the Police Court at Nassau in the early part of 1887, a case occurred showing the ideas prevailing in the colony on the subject of equal rights. Mr. George Bosfield, an educated coloured gentleman, was summoned before me for violating an Act of Parliament, compelling houses within the limits of the city, to be built in a certain way. Being possessed of a considerable amount of gumption, Mr. Bosfield filed informations against seventeen leading white men for violation of the Act, whom acting Police Inspector Crawford was compelled to

43

44

summon. After repeated applications for adjournment, the summonses were withdrawn, and the House of Assembly repealed the Act! How different would the case have been had these seventeen been coloured instead of white!

"Not long ago a certain local Attorney was appointed acting magistrate. Some few years before there had been an application to strike this person off the rolls for gross professional misconduct; subsequently, when Acting Inspector of Schools, he had misappropriated public funds, and would no doubt have been prosecuted had he been a coloured man. Being a white man, and related to some of the most influential members of the clique, he was allowed to repay the money in installments.

"In two cases in which white men prosecuted black for larcency, there being no evidence whatever to support a conviction, this person convicted and inflicted a nominal fine to prevent an action being brought against the prosecutor…

"About two years ago, a white man named Sands hit a black policeman. Sands was undoubtedly mad, and was acquitted on that ground. The way the whites talked of this habitually was, 'that the man was only a nigger, and it was a pity a few more were not shot.'

"I extract the following from a letter sent me by an intelligent coloured man:

" 'The family alliance is too great, its ramifications extend throughout every branch of the Government, Executive, Legislative, Judicial and Revenual. There is no hope for us except through the removal of the present holders of office.

" 'For many years the press of the colony has obstinately refused

to publish our grievances, and the people are cowed down, afraid to make

any public lawful demonstration or stand up for their rights, liberties,

and privileges, as they are deterred by the oft-repeated threat of reading

the Riot Act, and bayoneting the people by the soldiers. The dominant

minority have the ear of the Government at home, and make use of their

influence and prestige to crush and oppress us. We have no chance in the

Halls of Justice, if our opponent be a member of the clique. In the public

service we are superseded by the sons and younger brothers of powerful

members of it, and our services, though long and faithful, are ignored.

" 'For us as a people, there is no hope, unless the present higher

officials—who are either connected with the clique or else in debt

to them—are removed, and their places filled by men from England.

Unless we get help and aid from Great Britain, our condition will soon

become unbearable!'

" A member of the New York Yacht Club, who knows the Bahamas thoroughly, once said to me, ' I was here the day Sands was arrested, and I never shall forget it as long as I live! No one who saw that crowd could doubt there was an undercurrent of race-hatred with which the white Conchs will have to reckon sooner or later.' There was an American lady staying at the hotel last winter, who made it her business to get at the bottom of the coloured people's thoughts and feelings. She went out sailing every day with the same boatman, and completely gained his confidence. One day he said to her, ' If it wasn't for the soldiers, we would cut the throats of every white Conch in Nassau.'

"I am told that shortly before I left, Jamaica men were going about telling the people the history of the Jamaica outbreak in Governor Eyre's time, and one of them even went the length of saying, 'If you burn down Bay Street, the whites haven't got a saviour among them. In Jamaica they had lots of saviours, but we burnt the town.' This, my informant explains to me,

45

meant that whereas in Jamaica, white and coloured people held property side by side; Bay Street, which is the principal business street in Nassau, belongs entirely to the white merchants.

"Would that my pen might have power enough to impress upon the Colonial Office the necessity of being wise in time, and not lightly setting aside a petition for a Royal Commission if it should happen that one is sent in with that object. These people know enough of the history of Jamaica to know that the blacks were oppressed there; that they broke out under Governor Eyre, and that, though Gordon was hung, a Royal Commission was sent out, and the coloured people have been better off ever since.

"In fact I am told on all hands that not only in Jamaica, but throughout the West Indies, the coloured people are a great deal too well off, and it is common to say they are unbearable. Whether this be true or false, I have no means of knowing. I do know what their condition is in the Bahama Islands, I know that it is disgrace to the British flag, and above all I know that I have promised them to do my best to bring their wrongs before the British public.

" If the struggle for emancipation fifty years ago was really a struggle for a principle and not merely a struggle to get rid of an ugly-sounding name, if the soil that produced a Granville Sharp, a Wilberforce, and a Clarkson, still bears fruit of a like kind, they ought not to cry to England for assistance in vain. For never was there a time when the maxim that a black man has no rights which a white man is bound to respect, was more firmly believed in or more persistently acted on, than it was in the year of Jubilee in the Bahama Islands.

"For this state of things I believe there are two remedies. Let England persuade the United States to take over the country; or failing that, at once turn it into a Crown Colony. In the first case the independent assembly would disappear, and the country would become 'Bahama County.' 'Florida,' or 'South Carolina,' to which state it belonged before the separation from England. It would send one, or at the outside two, deputies to the State legislature, one good Yankee firm would eat up the little Nassau hucksters without stopping to take breath; the interests of the place as a winter sanatorium would be pushed, and the whole condition of things transformed in an incredibly short space of time.

"As an Englishman of course I dismiss the idea of annexation to America as not to be entertained, but I cannot shut my eyes to the advantages that would accrue to the country from it. and if a colony is worth keeping under the English flag, England should do her duty by it, and that she certainly does not do in the case of the Bahama Islands.

"The coloured people would not sever their connection with this country on any consideration. They associate England, and especially Queen Victoria, with emancipation, and are intensely loyal, because they are a grateful people, though their enemies are for ever proclaiming the contrary. Their faith in the Queen is unbounded, they call her 'The good missus', and believe firmly that if she only knew their troubles, they would be redressed at once."It is of course not easy to change the constitution of a colony, but it would be very easy for England to promote of the present holders of office, who are men of ability and really good instincts, and who, in another colony away from the ties of family, would be good and useful servants to the State. Where they are it is next to impossible for them to do their duty.

"Bug in order to fill their places with really good men from England, it will be necessary to increase the salaries sufficiently to make worth the while of men who are worth having to take the places.

46

47