- Grand Bahama in 1887 from L. D. Powle The Land of the Pink Pearl or Recollections of Life in the Bahamas.

- Grand Bahama in 1891 from Stark's History and Guide to the Bahama Islands.

- Grand Bahama in 1917 from Amelia Defries In a Forgotten Colony

- Grand Bahama in 1924 from The Tribune Handbook

- Grand Bahama in 1926 from Mary Mosley The Bahamas Handbook.

- Grand Bahama in 1931 from Nassau and the Treasure Islands of the Bahamas

- Grand Bahama in 1934 from Maj. H. M. Bell Bahamas: Isles of June

- The Bahamas in 1964 from Benedict Thielen The Bahamas-Golden Archipelago

- rand Bahama in 1967 Moral Panic, Gambling. and the Good Life

Ten, Ten The Bible Ten : Obeah in the Bahamas

Dr. Timothy McCartney

Nassau: Timpaul Publishing (1976)

SECTION II

ASPECTS OF SLAVERY (Continued)

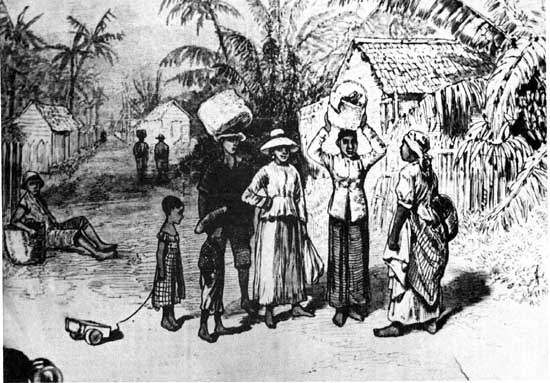

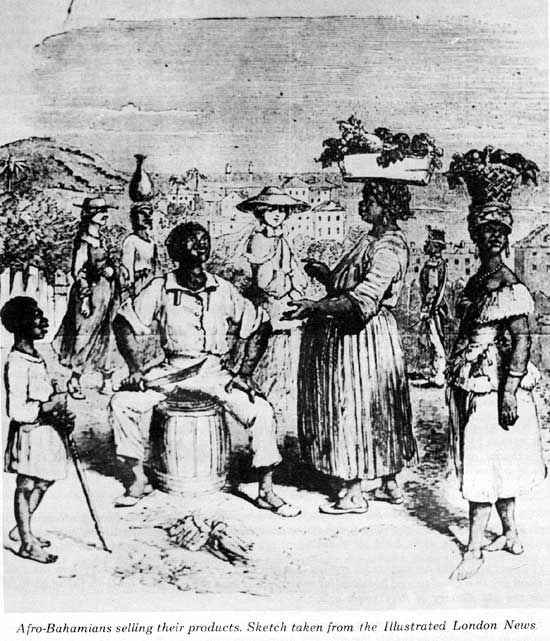

| SCENE IN GRANTS TOWN— The settlement of Grants Town, situated on the island of new Providence was inhabited mostly by ex-slaves and liberated Africans who were captured by the Royal Navy and freed on reaching | Nassau. Grants Town used to be a very wooded place with many fruit trees. Each house had its own garden, filled with trees, vegetables and fruit. |

26

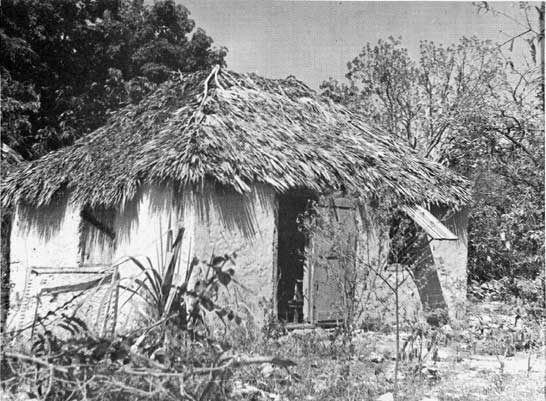

This "thached roof" house was typical of the type used in the Bahamas by the population. Many of these houses are still used by familes today.

27

class and social structures, were deplorable, so basic survival in the Bahamas, as elsewhere, was the primary goal. From a population point of view, the inhabitants on any one island could number anywhere from a single family, to thirty or to a thousand. This small number of people in the Bahamas, at this period, was a sad commentary on the systematic depletion of the Lucayan Indian population by the Spanish, which was estimated to be nearly 20,000 when Columbus first came.

The political situation, at this time, was unstable, with conflicts of ownership primarily between Spain and England. The First official English colony was formed in the Bahamas in 1648 with the coming of the Eleutheran Adventurers.

(2) Slavery

The Portuguese, as early as 1503, were importing negro slaves from Africa,

because of the demand for labourers, primarily by the Spanish, in the

West Indies after the native population (the Caribs and Arawaks) had just

about been exterminated. When the British made significant inroads in

the West Indies, slavery had become a fact and way of life, and the Bahamas

was caught up in this activity.

The population of the Bahamas increased appreciably when, during the War of American Independence, Loyalists, with their slaves, immigrated to the Bahamas. By 1789, the population was about 11,300 with about 8,000 Negroes, and about 8,000 New Loyalists. Most of these Loyalists settled in the uninhabited Out Islands and set up plantations there. Nassau, also buzzed with activity. McKinnen gives an interesting account of the Bahamian slave trade.

The Bahamas 38 “appeared to be visited often whilst I remained there by African slave-ships, some of which disposed of their cargoes on the island, but the majority proceeded to the Havannah; I was witness to the sale of a pretty numerous cargo, which was conducted with more decorum, with respect to the slaves than I had expected. They were distributed mostly in lots from five to twenty in each; but some.of the boys and girls were disposed of separately. On the neck of each slave was slung a label specifying the price which the owner demanded, and varying between two and three hundred dollars according to age, strength, sex, etc. This cargo was composed, as generally happens, of slaves, from different nations, and speaking languages unintelligible to each other. Some apprehensions prevailed notwithstanding all the expedients which had been used to convince them to the contrary, that they were brought over to be fatted and eaten. I had the opportunity of observing two or three the day after the sale in the hands of benevolent masters purchased for domestic servants, who seemed much delighted with their kind treatment as well as change of situation. Instead of being naked, they were clothed (in this climate as usual) in woolens; their food was much superior to what they had ever known before,* they found themselves lodged in habitations abounding in comforts, some of them indeed superior to their comprehension; and in the streets, they beheld many of their own colour, whose appearance, friendship and hilarity had the most powerful influence in rendering them contented and happy in their new scene in life.''

McKinnen must have been quite a naive fellow, or he was in the right place at the right time, to make such a sweeping statement, because many slaves were ill-treated and not placed in such benevolent circumstances. It does appear, however, from other written accounts of this period, that, on the whole, Bahamian slaves were treated fairly well.

38. McKINNEN. Daniel. "A Tour Through the British

West Indies" London, 1804. pp. 218-219.

* How the hell did he know this? Had he ever lived in Africa or eaten

African food?

28

Sales of slaves were held mostly in "Vendue House" which is, at present, the site of the Bahamas Electricity Corporation. Cattle and imported goods were also auctioned here.

Another author, in observing the tribes of the Bahamas, writes "seven African races are known to have been introduced into the Bahamas: Nangos, Congos, Congars, or Nagobars, Ebos, Mandingos, Fullahs, and Hausas. Any racial distinctions which might once have been apparent have long since disappeared with the passing of time. Some of their practises, however, their folk tales, and their dances, reveal traces of African ancestry." 39

This author appears to be also a bit deluded because Sir Etienne Dupuch, the distinguished editor of the Tribune, recently stated, in an editorial written from the Bahamian island of Exuma: "I knew Exuma when anyone landing on the Island might have thought he was in darkest Africa at the time of Dr. Livingstone's exploration in the Dark Continent. At the Forest, the villagers were still living in the small thatched two-room huts occupied by their ancestors in the days of slavery. The compound was surrounded by a low rubble-stone wall with no gate. People in the compound jumped the wall like goats to enter and leave. There were no schools in the village. This was 67 years ago. I was with my mother at the Forest for a month." 40

Certain peculiarities of Bahamian slavery and the Bahamian plantation system are significant:

(a) The Bahamas has never been an agricultural country. True, certain seasonal crops like pineapples and tomatoes thrive and were articles of export. During the period in question, the poor soil only allowed cotton to be grown and small farming. Europeans, limited slaves, free men (black and white) existed by taking sustenance from the rich waters surrounding the Bahamas, and the small farming previously described. During slavery, then, plantations were comparatively small, and the Plantation System, as was known in America, and other islands of the West Indies, where sugar cane, tobacco and other "exotic" products were grown for European consumption, did not exist in the Bahamas. The Plantation System, however, resembled, on a small scale, a share-cropper arrangement unlike the Southern United States, which "might have been hard on the tenants, the owners of big acreage in those days got little more than a bare living out of the operation." 41

Plantations were comparatively small.

The Hermitage Estate on Little Exuma consisted of 900 acres and had only 160 slaves (men, women and children). Bourbon cotton was the main crop; salt was also raked, and animals such as cattle, horses and mules were bred.

The most comprehensive and only (so far) existing account of a Bahamian plantation, has been described and preserved in "A Relic of Slavery", a diary written by Charles Farquharson for the years 1831-1832 and published in 1957 by the Deans Peggs Research Fund. This plantation, situated on San Salvador, included a dwelling house, a mistress house, the kitchen, a corn house, a cotton house, a lower barn and slave quarters. There were only a maximum of 52 slaves, and the main crop was guinea corn, although the commercial crop was cotton. A considerable amount of stock was raised on this estate and it was used for their own consumption, but periodically shipped to New Providence. Lord John Rolle (1750-1842) was probably the largest slave owner in the Bahamas. His official slave count at the Emancipation was 377.

39. "Folk Tales and Songs" - 1930.

40. DUPUCH. Sir Etienne. "Looking Back Over the Years" (editorial)

The Tribune. Tuesday. October 1,1974

41. DUPUCH. Etienne (Sir) Ibid.

28

The Heritage Estate on Little Exuma belonged originally to John Kelsall Member of the Governor's Council, Senior Assistant Justice of the General Court and Judge of the Court of Vice-Admiralty who died in 1803. It is now the property of Vincent Bowe.

The Estate once consisted of over 900 acres and raised Bourbon Cotton. Salt was also raked on the plantation.

In 1806 the Royal Gazette in advertising the Hermitage for sale stated that " With the Hermitage will be sold an uncommonly fine gang of seasoned Negroes, the whole number not less than 160 men, women and children."

Part of the present building dates back to the original twin-gabled barn-like edifice which had various smaller buildings around it.

30

Farquarson's estate is named after Charles Farquarson who wrote a journal

for the years 1821-1832 which has been published as "A Relic of Slavery".

The Plantation, a large estate on the east side of San Salvador, is one

of the largest on the island

Charles Farquarson, who was also a Justice of the Peace, owned fifty-two slaves in 1834 and according to the diary he appeared to have been a kind master to his slaves.

The Chief Crop of the Estate appears to have been guinea corn. The Chief Commercial crop, though a declining one, was cotton. A considerable amount of stock was raised on the estate and shipped periodically to Nassau.

The buildings on the estate included a dwelling house, a Mistress's house, the kitchen, a corn house, a cotton house, a lower barn and slave quarters.

The photograph shows the remains of two houses on the Farquarson estate. Perhaps the one in the foreground is the kitchen within its traditional fire-place and chimney. The buildings were constructed of native rock and limestone. Notice the corrosion that has taken place over the years.

31

slaves. When slavery was abolished, Lord Rolle deeded all his extensive lands in Exuma to his slaves and their descendents in commonage.

Rolle owned extensive land holdings in Rolleville, Rolle Town, Mount Thompson and Ramsey. The Bahamian name "Rolle" is extensive and, no doubt, came from the original Lord Rolle, who was a benevolent slave owner. The white (or European Rolles) left the Bahamas and, to the author's knowledge, there are no Bahamian "white" Rolles - unless they have changed their names!

Many Bahamians are mixed, no doubt, from the intimate infusion of white or black and vice versa. The paternalism and benevolence of the slave owners plus the very good relationship of the master to his "house niggers" (of which there were many) contributed to the fact that there were no slave revolts or uprisings.

Around 1830, there were abolitionists throughout the Bahamas - liberal white men, members of the clergy and some free black men (lay and clergy). The infrequent incidents of cruelty pricked the conscience of the small Bahamian population, and although there was very strong resistance to the abolition of slavery, laws against cruelty were passed. These laws were especially enforced under the governorship of Sir James Michael Symth (1779-1838) who was a sincere sympathiser with the cause of the slaves and free coloured people and worked diligently for greater amelioration of slave conditions. There were members of the white ruling population who violently objected to the abolition of slavery. Reports in the local newspapers and letters to the colonial office in England, and from the Bahamas, attested to this fact.

(b) Because of a limited agricultural system, limited exports to foreign countries, and small estates, after emancipation, there was no need to continue working the plantations as there was no great demand for any Bahamian products. Throughout the Caribbean, after emancipation, the plantations still had to produce hence, Chinese, Indian and other labourers were indentured to plantation owners in the Caribbean.

This never happened in the Bahamas. Where there is found in most of the West Indian islands a diversity of ethnic types, the basic population continued to be majority black, minority white, and some in-betweens (who could go either way), as evidenced in descendents from Long Island, Eleuthera and Exuma.

The small number of Greeks, Chinese, Syrian and other minority groups, as found in present day Bahamas, came either during the "sponge industry boom" or the early part of the 20th century.

(c) Those Africans who were never placed in slavery, settled in areas of the Bahama Islands where, even though they were subjected to discrimination by a minority, but powerful, white population, established their own social and cultural life.

These Africans, generally, "looked down" on the majority Negroes who were Christianised and in former bondage. The former slaves regarded the free Africans as preserving much of the culture that they had lost, but still yearned for and looked up to the "Wise Men" - Healers, Herbalists and Obeah Men - for guidance. These were the aristocrats of the Black Bahamian Society, which perpetuated their own system of social class and discrimination, based on heritage and, primarily colour.

32

3. Post Slavery

This period should be headed colonialism, racism, social class and discrimination,

because it seems as if, after emancipation, problems for the Negroes just

began. The majority of people were black; but the Bahamas operated under

a white power structure, not too unlike the United States of America,

especially the Southern States.

There were no laws or regulations fixing the status of the black people, but they were subjugated to a position of inferiority that placed them solidly on the bottom of the social structure.

During this period, liberated Africans and ex-slaves lived in specific areas and were well known for their heritage (family). For example, Grant's Town was one of these areas where a large African population was found. Stark 43 describes living conditions: "The Houses are mostly of wood, some with limestone walls, roofs covered with shingles or thatching of palmetto leaves; it is rare to see glass windows, instead there are board shutters. They light fires out of doors, for cooking from dead wood gathered in the forest or thicket; the walls are not sheathed or plastered; the furniture is of the most modest and simple kind; in day time they live out of doors. A little sugar cane, a few conchs or fish, a handful of fruits fills to overflowing their wants."

From an interest point of view, Powles 44

describes the house of an English clergyman, with his wife and two children:

"A house larger than, but about on a level with, an English labourer's

cottage, containing two rooms and an apology for a study something like

a store-closet. No ceiling, merely a partition between the sitting-room

and bedroom, that anyone could look over by standing on a chair; only

a solitary window glazed and scarcely one of the little comforts that

would be found in the poorest home in England. And this, not in a savage

land, but in a country which has been nominally civilized for one hundred

and fifty years, and where, but fifty years ago, the planters lived as

I have described.

Thus, life was of a fairly primitive, simple nature with the different social classes and British colonialism playing a very important role in Bahamian life, and the Bahamian value system. During slavery, and soon after the abolition of slavery, Bahamian blacks were aware of and perpetuated their African ties. However, the minority whites, who held the political and economic power, plus the very strong British colonial hold, questioned their rights and value system, Discriminatory attitudes and practises were everywhere - in schools, banks, clubs, hotels and residential areas. Very rarely, did black and white Bahamians have any meaningful social intercourse. Perhaps the only objective document available that depicts the lifestyle and politics during this period has been preserved in a book by an Irish Catholic Magistrate, L. D. Powles, who came to the Bahamas in the Autumn of 1886 from England as Circuit Justice in the islands. Powles' book, "The Land of the Pink Pearl", created such a furore among the white Bahamian population, (because of the truth of the situation and his sense of fair play) that Sir Ormond Drimmie Malcolm, Chief Justice in the Bahamas at that time, bought five hundred copies and burned them!

* For an in depth analysis of the effects of racism, social

class and colonialism, see the author's book "Neuroses in the Sun".

Executive Ideas of the Bahamas. Nassau, Bahamas. 1972.

43. STARK. J. H., "History and Guide to the Bahamas". New York.

1891.

44. POWLES. L. B."Landof the Pink Pearl: Life in the Bahamas"

Sampson Low, Marston and Co. Ltd.. London. Pg. 236.

33

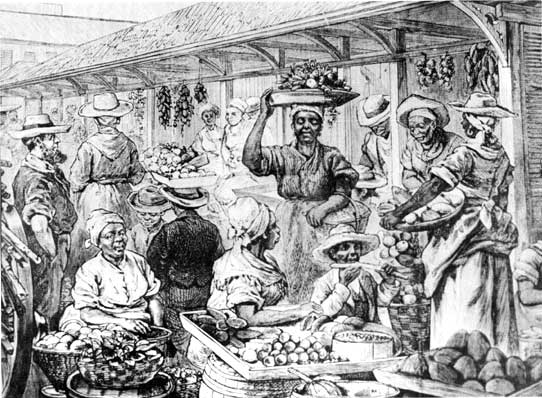

MARKET SCENE IN OLD NASSAU — The Bahamian market has always been

a very colourful scene. This sketch was done around the early 1900s.

34

35

It is significant to this book, and indeed the history of the Bahamas, that I quote Powles extensively: -

"The constitution of the colony is a sort of government by Queen, Lords and Commons, without a responsible Ministry. The Governor is assisted by an Executive Council, answering to the Privy Council, appointed by himself. He also appoints the members of the Legislative Council of 'Upper House,' whilst the Legislative Assembly or 'Lower House' purports to be elected by the people.

"This mockery of representation is the greatest farce in the world. The coloured people have the suffrage, subject to a small property qualification, but have no idea how to use it. The elections are by open voting, the bribery, corruption, and intimidation are carried on in the most unblushing manner, under the very noses of the officers presiding over the polling-booths. Nobody took any notice, and as the coloured people have not yet learned the art of political organization, they are powerless to defend themselves. The result is that the House of Assembly is little less than a family gathering of Nassau whites, nearly all of them are related to each other, either by blood or marriage. Laws are passed simply for the benefit of the family, whilst the coloured people are ground down and oppressed in a manner that is a disgrace to the British flag. . . .

"In every one of the principal out-islands there are one or more resident magistrates or justices. They are paid salaries varying from £301 to £2001 a year, for which they have also to perform the duties of revenue officers. Formerly, properly qualified magistrates, sent out from England, went regular circuits round these Islands for the administration of justice; but about thirty years ago the last of these disappeared, and the present system of resident justices was inaugurated.

"Against the decisions of these justices, the majority of whom are devoid of any special qualifications for their places, there was no appeal except to the Chief Justice sitting in Nassau. The people were all so poor not only was this appeal virtually a dead-letter, but the jurisdiction of the resident justices being very limited, there were many cases that, for want of means could never be brought into a Court of First Instance.

"Without giving credit either to one story which charges a magistrate with causing the death of a woman by ill-treatment, or to another which relates how a magistrate who did not wish to be bothered, adopted the plan of locking the parties and witnesses all up together till the case was abandoned, there is no doubt that acts of tyranny and oppression were daily committed…

" 'The bulk of them are just as much slaves as they were fifty years ago!"

"These words were surd to me shortly after my arrival in the Bahamas, by a gentleman who had excellent opportunities of judging of the real condition of the coloured race, and was well acquainted with it.

"I asked him what he meant. He replied 'I mean that by means of the truck system the bulk of them are in a condition of bondage far more galling and far less profitable to the individual than the old slavery of fifty years ago.'

"This was a startling statement, and difficult to believe, for the first impression one gets on landing in the Bahamas is that the coloured people appear so remarkably contented that there cannot be much the matter with their condition. Wherever one meets them they seem cheerful

36