- Grand Bahama in 1887 from L. D. Powle The Land of the Pink Pearl or Recollections of Life in the Bahamas.

- Grand Bahama in 1891 from Stark's History and Guide to the Bahama Islands.

- Grand Bahama in 1917 from Amelia Defries In a Forgotten Colony

- Grand Bahama in 1924 from The Tribune Handbook

- Grand Bahama in 1926 from Mary Mosley The Bahamas Handbook.

- Grand Bahama in 1931 from Nassau and the Treasure Islands of the Bahamas

- Grand Bahama in 1934 from Maj. H. M. Bell Bahamas: Isles of June

- The Bahamas in 1964 from Benedict Thielen The Bahamas-Golden Archipelago

- Grand Bahama in 1967 Moral Panic, Gambling. and the Good Life

Ten, Ten The Bible Ten : Obeah in the Bahamas

Dr. Timothy McCartney

Nassau: Timpaul Publishing (1976)

CHAPTER IV

PSYCHO-SOCIAL ASPECTS OF OBEAH

SECTION II

Obeah and Folklore

Three years ago, a Bahamian musician, resident in New York,

suddenly burst on the international and Bahamian scene with songs that

all Bahamians could readily identify with. He was Tony MacKay, a Cat Island-born

Bahamian who called himself "Exuma, the Obeah Man". Kifaru Magazine

1 described him—"Everything is a bit mysterious

about Exuma, from his outfits to his music, his paintings, his poems,

his life. 'Exuma is one.' he has written. 'Exuma is three. One, two, three,

they all can see.' Also, 'his time is short, his time is long. Exuma ain't

right and Exuma ain't wrong.' Also, 'Exuma took his wooden hand and scorched

his mark across the land.' Mysterious."

1, KIFARU, "Tony MacKay is Exuma the Obeah Man", VOl. 3, NO.

1, 1974, BOX 2942, Freeport, Grand Bahama.

134

It is significant also, that three years ago, Obeah had reached its 'height' on the comeback road in the Bahamas and Exuma's rhythms and songs not only highlighted a practice that was embedded into every Bahamian's psyche, it provided a meaningful departure point for the search for cultural expression and a projection of African beliefs that had relevance to a newly independent Bahamas.

The practice of Obeah, the supernatural and cultic activity occur in the writings of West Indian authors from all ethnic groups.

Ramchand 2 writes: "The degree of prominence given to them varies from novel to novel; and the authors' attitude to their raw material differ widely. J. B. Emtage introduces negro terror of the fetish in a mocking and comic spirit ('Brown Sugar', 1966) but another white West Indian, Geoffrey Drayton, uses Obeah differently in the novel of childhood ('Christopher', 1959). The boy's increasing involvement with the negro world around him, and his growing up process, are subtly correlated with his development, away from the exotic view, to an understanding in psychological terms of how Obeah operates. Sociological truth and a comic intention are both served in V.S. Naipaul's version of Obeah in 'The Suffrage of Elvira' (1958)."

Ismith Khan, in his novel 'The Obeah Man' (1964), describes Zampi as follows: "An Obeah Man had to practice at distancing himself from all things. He had to know joy and pleasure as he knew sorrow and pain, but he must also know how to withdraw himself from its torrent, he must be in total possession of himself, and at the height of infinite joy he must know with all of his senses all that lives and breathes about him. He must never sleep the sleep of other men, he mush have a clockwork in his head. He must, at a moment's notice, be able to shake the rhythm from his ear, to hold his feet from tapping. He must know the pleasure in his groin and he must know how to prevent it from swallowing him up."

There has not been any attempt by foreign or Bahamian authors to deal with Obeah in the Bahamian setting. The practice is cursively mentioned in novels and history books, but there is nothing to approximate the work of Naipaul, Khan, Sylvia Wynter, Orlando Patterson or Edward Seaga's exploration of Obeah, religion or cults in the Caribbean.

The superstitions and beliefs of the Bahamian people have been perpetuated by 'word of mouth' and 'old stories' that have been passed on from generation to generation by parents, grandparents and relatives.

These stories, superstitions and myths are mixtures of African and Euro-American beliefs. Ford 3 states that "Myths, in the sense of bases for religion, are not extensive in the Bahamas, although ritual myths exist; superstitions, as deterrents, are a different matter. In fact, they act almost as strongly upon our folkways as social sanctions do in any small society. It is possible to trace the degree to which superstitions control the actions of people, if one reasons along the theory that 'education' or enlightenment usually dispel the fears that are naturally a part of ignorance. Needless to say, superstition was also the seed-bed for the birth of Obeah, witchcraft or feeack, as our earliest West Indian immigrants referred to it." Ford continues: "Obeah men and women thrived well in the early part of the century. People went to them (some secretly at night) to have certain events and conditions 'fall' at set times, on selected

2 RAMCHAND, Kenneth, "Obeah and the Supernatural

in West Indian Literature", Jamaica Journal Vol. 3, No. 2, June 1969.

Institute of Jamaica, Kingston, Jamaica.

3. FORD, Dorothy, "New World Groups: Bahamians", Printed by

the Nassau Guardian (1844) Ltd., 1971, Page 16.

135

people. The fact that a great number of these events did 'fall' on the parties, envied or cursed, only added to the mischief."

Curry wrote in 1930 that Bahamians' "folk tales and their dances reveal traces of African ancestry. Occasionally, you may hear of a form of 'black magic' being attempted, but this is rare. The people are religiously inclined, in a childlike way; although, on the other hand, they can be incredibly superstitious. Their group dances consist usually of shuffling movements with accompanying chanting and a beating of time with the hands; in the dances where circles are formed, the chief performers are in the centre. There is a tom-tom rhythm to the dances." 4

'Old stories', 'music', 'rhythms' and 'Obeah stories' have always been integral parts of the Bahamian way of life. Religious beliefs, ideas of references to heaven, hell, sperrids, angels and the Devil, abound in the stories and songs of Bahamians. "Morals and morale-building were so greatly interwoven that one aspect cannot be separated from the other: the myths contributed greatly to the music, the music belonged to the people and lyrics were improvised for the purpose of morale-building. Adlibbing or 'rigging', as the old Bahamians termed it, went on for hours at a time and supplied fun for all concerned. Morals controlled the songs of necessity: the children could not be despatched anywhere (all members of the family were within shouting distance and facilities were close at hand) so they were in on every move the adults made. As children were not aware of anything implied in the songs, the composers were as adept as Doane in disguising the real meaning of words, so when we sung in imitation of them, 'Mama look up in daddy's face all night long,' it never entered our guileless minds that mama and daddy were doing anything else but sitting down facing each other, talking all night. The image of adults sitting up, talking all night, was a familiar one; the other action was not." 5

In trying to understand the relevance of Obeah and folklore, one must go back to the source and examine the Bahamians' ancestors (Africans) who were uprooted from their societies and cultural settings and placed in a new cultural environment. Added to this transposition was the other Euro-American influences that moulded the African through religious missionary zeal, and both clerical and secular education to conform to that colonial ideal. There were gradual displacements of African names, beliefs, superstitions, foods, festivals and holidays. "Since the object of the plantocracy was to retain its wall of social and political authority in the Caribbean, it supported these two 'missionary' drives with social legislation designed to prevent the former slaves from achieving very much in the community. Their voting rights were restricted, their socio-economic mobility curtailed, and their way of life brought under subtle but savage attack. Shango, Cumfa, Kaiso, Tea-meeting, Susu, Jamette—carnival—all had to go." 6

Surely, the suppression of the Bahamian-African's cultural expression was discouraged. To begin with, the majority 'house slaves', christianized and emulating their masters, looked upon African cultural expression as being 'pagan'. The minority 'field slaves' were not sufficiently tribally strong to find common grounds for expressions. Except for the islands of Cat Island, Exuma and Andros, where the retention of African practices were strongest, the majority of Afro-Bahamians followed strongly Euro-American cultural traditions.

It is significant though, that through research, Bahamians are realizing the importance of the "remoteness" of the Family Islands. Slaves and free Africans who were concentrated in

4. CURRY, Robert A,, "Bahamian Lore-Folk Tales and

Songs," Paris, 1930.

5. FORD, Dorothy, op. cit. Pg. 16.

6. BRAITHWAITE, Edward Kamu, "The African Presence in Caribbean Literature",

op. cit. pg. 75 and 76.

136

isolated "pockets" in these islands, maintained their culture - the expression of which, today, are represented in an almost unchanged art form.

These islands free from Euro-American cultural infusions that invaded New Providence and Eleuthera, for example, never projected expressions that were found on Southern U.S.A. Slave plantations. Comparatively, in other West Indian Islands where slaves escaped to the "interior", almost "unchanged" cultural expressions can be found.

Bahamian rhythms have been compared very much to Brazilian rhythms, although in Brazil, Portuguese influence and traces of indigenous Indian models make interesting rhythm expressions.

There were generally four annual holidays during slavery: Christmas, Boxing Day, New Year's Day and Easter. Both master and slaves participated in these 'festivals'. After slavery was abolished, Fox Hill Day when only those of African descent celebrated, and August Monday (Emancipation Day) were added to the people's festivals, although Fox Hill Day was not a public holiday.

There was no retention of any African festival as such in the Bahamas. No yam festival or river (or water) festivals were commemorated. The Bahamas never enjoyed such outstanding harvests of yams as to occasion the celebrating of them. Harvests of sponges, pineapples, tomatoes and conchs have been sung about, and Bahamians improvised words and music as they suited the current events.

Harvest time was celebrated as a religious festival of thanksgiving by the white population (mostly American) and was not a public holiday. It was also incorporated into the church. services of the majority Black Christian denominations on a seasonal basis. This was not unusual since the major denominations for blacks in the Bahamas were started by free American Blacks who had been converted to Christianity.

In "A Relic of Slavery" (Life on a Bahamian plantation) the great festivity of Christmas and the lesser celebration at harvest, gain mention but the day, Sunday, itself, is totally omitted except that some Sundays the slaves still had work to do. It is interesting to note, however, that there were family prayers every morning on this plantation, which were attended by the 'domestic' servants.

Emancipation Day was a great holiday for the Bahamian. "Everyone ditched work and headed for Fox Hill by whatever means of transportation he could muster. For the majority, this meant walking; therefore, the trip from Grant's Town, Bain Town and Conta Butta * started early in the morning along the winding foot-path of what is now Wulff Road and Bernard Road. The weeks of preparation undergone by the various tribes resulted in a day of highstrung festivities: dances, quadrilles, concerts and jumping-dance. The entire community moved round as a whole, going from one church to lodge hall to the next, thus allowing for everybody to see everyone' else's performance prepared for the day."

By far, the greatest pre and post-slavery, celebration was Christmas when Bahamians had an almost 'free rein' to do their 'thing'. This fact persists even today!

The preparation of food and the preparation of the Junkanoo festival with the making of costumes, became a joint family neighbour venture. Unlike carnival in other West Indian

*All African settlement on the island of New Providence.

137

138

countries and countries with a strong Lenten tradition, when the celebrations precede Lent, carnival (or Junkanoo) is celebrated during the Christmas season with official Boxing Day and New Year's Day.

The original Junkanoo, reputed to be the corruption of John Canoe (reputedly an African or 'Gensinconnu' - meaning individuals with masks, is the strongest remnant of African tradition.

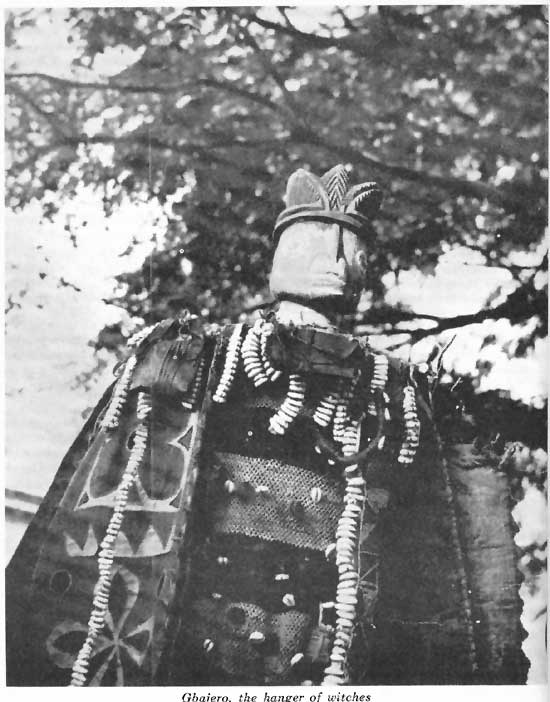

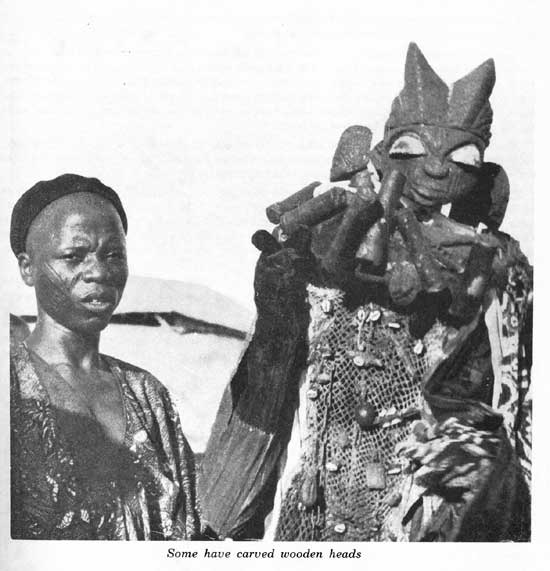

As previously postulated, the majority of Bahamians appear to have come from the Yoruba tribe, and early Junkanoo practices resemble costumes worn by individuals of the Egungun

139

cult. The Yorubas, like most African tribes, worship their ancestors. This worship is based on the belief that the spirit of a human being never dies.

Egungun is a secret society of masqueraders headed by a hereditary chief called 'Alagba'. An Egun mask usually represents the spirit of a particular person and it is always the priest of the Ifa oracle who will decide which spirit must receive special attention. The masks are of different types. Many consist of coloured cloth and leather, covering the whole body of the dancer, who looks out through a closely-knitted net. Some have actually got masks in front of the face, while others again wear a carving on top of the head.

Junkanoo is found in Jamaica and other of the smaller English-speaking Caribbean islands, although it would appear that the Bahamas has retained Junkanoo and projects this in a more elaborate fashion, and developed Junkanoo that is distinctly Bahamian.

Patterson 7 suggests that "John Canoe was originally derived either from one of the dances of West African secret societies or from the main dance of the band of hired entertainers, or, more likely, from both these sources." He continues that "Cassidy's * etymology for John Canoe - the Ewe word meaning sorcerer - man or witch doctor - strengthens our case, when it is noted that witch doctors were often the heads of secret societies and, themselves, performed the main ritual dance performed."

Bahamian original Junkanoo dancers wore costumes of cloth or frilled paper.+Many of the 'masks' were just paintings on the facial skin itself, and the projection of the Obeah man was usually the one dressed in white with a white mask or paint on the face jester-like. There were also 'stilt' dancers, street dancers, clowns and acrobatic dancers. The Bahamian flavour was added by costumes made of sponges. These Junkanoo dancers were accompanied by the goombay** drums (goat-skin stretched over a wooden frame and heated to obtain the maximum sound), whistles and another Bahamian adaptation, the cowbell.

From a comparative point of view, in Belize, British Honduras, the stilt-dancer, who appears in a parade at Christmas time, is called 'John Canoe' and in Barbados, the central figure of the Christmas masquerade parade used to be a stilt-dancer who controlled the dance with a tin rattle.

In discussing the interaction of cultures in the Caribbean, Beaubrun

8 states that "Whenever two cultures

interact, some change is inevitable in both of them, and the change may

be for good or bad. Dr. Stephen Proskauer, at one of our W.F.M.H. meetings,

attempted to categorize such interactions using the terms adculturation,

abculturation, synculturation, dysculturation.

'If my memory serves me right,' Beaubrun continues, 'adculturation refers

to the beneficial

growth of a culture by this contact. Abculturation would be where a culture

loses by such

contact. Synculturation is where both cultures grow and are improved by

contact with each,

other, and dysculturation where both are harmed by the interaction."

To fully understand Bahamian Obeah and folklore, the process of acculturation, which consists of acquiring another culture, losing most of a previous culture and the creation or adaptation of new cultural expressions, must be explained.

7 PATTERSON, Orlando. "The Sociology of Slavery",

op. cit. Pg. 246.

* CASSIDY, F.G., "Jamaica Talk: Three Hundred Years of the English

Language in Jamaica", London, 1961.

* * Gumbay in Jamaica; gombey in Bermuda.

+Another local adaptation was the use of sponges on a type of cloth netting

worm over the body.

8. BEAUBURN. Michael, "Mental Health and the Interaction of Cultures

in the Caribbean", Keynote address at the Biennial Conference of

the C.F.M.H., Caracas, Venezuela, 27-7-75.

140

141

Junkanoo Costumes

142

The acculturative process in Bahamian Obeah may be thought of in

terms of:

(1) Total or nearly total African retentions

e.g. retention of fetishes, drums, whistles and rattles, cowbells emphasis

on rhythm and polyrhythms, use of animal blood in 'calling the spirit'.

(2) Afro-European syncretisms

e.g. funerals, wakes, beliefs concerning sperrids, possession by spirits,

the use of dreams in divining, folk tales.

(3) Euro-American borrowed traits and the reinterpretation of

Euro-American cultural elements.

e.g. the Bible, spirituals, hymns, revival, candles, the cross and crucifixes,

incense, divination by gazing into a mirror, a glass of water or reading

tea leaves, cutting the cards, reading the palms of the hands, religious

prayers.

Curry, 9 in 1930, wrote about Bahamian

folk tales and songs: "Their stories fall into two classes: those

which are the fruit of their own imaginings and traditions, and those

borrowed from such sources as the fairy tales in the English language

and Aesop's Fables. Many of the Bahamian stories will be found to have

a marked similarity with those of the negroes of the southern states of

America. It is indeed not always easy to distinguish the story of Bahamian

origin from one which has been imported."

Evidence of these stories are the Brer Bookie and Brer Rabbie stories

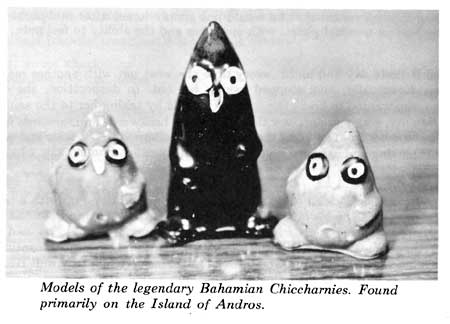

that are of the animal—trickster—hero folk type. The 'chiccharnies'

of Andros Island, are favourite mysterious-like, three-legged 'animals,'

that resemble the 'leprechauns' of Ireland. They supposedly live in the

9. CLIRRY, Robert A. op. cite.

143

silk cotton trees and get up to all sorts of mischief. The chiccharnie has become a favourite 'tourist' ornament, as replicas are made up in clay, glass and other memorabilia, with the varied stories surrounding them.

The most important Obeah folk tale, however (other than the millions of sperrid or ghost tales), is the Legend of Sammy Swain. This legend has been popularized by the brilliant Bahamian pianist composer, Clement Bethel, who has put this to music and dance.

"Sammy Swain was an ugly, old cripple who lived on Cat Island. He

was unliked by the people of the settlement because of the hideousness

of his person. He fell in love with a beautiful young girl called Belinda,

who was a real 'village belle'. She was much sought after and consequently

became very conceited. Sammy Swain fell desperately in love with the beautiful

Belinda and summoned the courage to ask her to marry him. However, beautiful

as Belinda may be, there was nothing kindly about her in her treatment

of Sammy and she laughed in his face and told him, arrogantly, what an

ugly, old fool he was. She also told him just how much she had to offer

and how sought after she was as well. Sammy was furious at the hard-hearted

way in which she rebuked him and his offer of marriage, and threatened

to sell his soul to the devil and come back and haunt her and stop her

becoming the woman of

another man.

The following day, Sammy's body was found with his head lying to the east and his face, therefore, facing west, which meant that he had done what he threatened to do. In one hand he had a hog's snout and in the other he had a ball which was half white and half black. These omens meant that whenever Sammy came to haunt, the snorting of a pig would precede his appearance and the ball meant that he would not simply haunt after mid-night but day and night. Sammy was an unusual ghost, with appetites and the ability to feel pain; he was also invisible.

He haunted Belinda day and night: every time she went out with another man something would happen. Eventually, men stopped asking her out. In desperation, she consulted an Obeah woman who wanted to break the spell on Belinda by taking her to the sanctuary of the church. But Sammy, very vigilant, saw this and moved backwards and forwards in front of the church door to stop her from entering the church. She collapsed to the floor and while she was lying there, old looking and haggard from the stress of haunting, Sammy saw what he had done to her and apologized.

Eventually, her father decided to do something about it and came up with a plan. The idea was to trap Sammy by using his favourite food as a lure and then to ship Belinda away from the island to Nassau as soon as possible. His favourite food was boiled fish heads, and so the father gathered the villagers together with cutlasses and these men laid in wait. Meantime, the pot of boiled fish heads was put on to cook and lure Sammy. And lure him they did! He came up and asked for a dish from them and the father told him, 'No, get away from here.' Sammy said that he would fix him if he didn't give him some and so he gave a plateful of this to Sammy. The idea was to strike at the direction of the fish as it travelled to invisible Sammy's mouth and kill him again. He did this but Sammy was only mildly wounded but the father called the villagers and they came running and striking out with their cutlasses and pursued the yelling Sammy back to the grave-yard. As he ran, he screamed out as every cutlass stroke hit home and he fell back into his grave and died a second death.

Meantime, Belinda was being put aboard the boat for Nassau.

144

She came to Nassau suffering from severe shock and probably a mild

seizure of the heart and was admitted to hospital. By now, she had been

through so much mental strain that her memory had gone. After months of

rest and careful treatment, she, one day, discharged herself from hospital

and disappeared. For three days her relatives searched the island of New

Providence for her and eventually found her dead, lying by a hedge. On

the other side of the hedge was a sow and her piglets and what had happened

was that Belinda, seeing the hog, suddenly regained her memory, and the

horrible events on Cat Island came sweeping back to her and she died of

a massive heart attack."

This is reputedly a 80-100 year old legend, but Mr. Clement Bethel, after

giving a talk on the legend, was told afterwards by a member of the audience

that 'Belinda' was, in fact, a great aunt of hers. So, like most legends,

it is partially rooted in fact, more than likely.

Belinda was, also, more bound to Sammy Swain than she thought and, although repelled by him, probably became reliant on his ghost in a bizarre sort of way. Perhaps the freeing of herself from the spirit on his second death, caused the physical trauma more than the haunting and brought about Belinda's physical breakdown.

Folk songs of the Bahamas initially were more religious, linked to slavery and freedom, as evidenced by the many spirituals.

These spirituals were primarily brought to the Bahamas by the slaves coming with their masters from U.S.A. plantations. The Bahamian spiritual, however, has added features that Clement Bethel describes as the "rhyming spirituals." He believes that it is a Bahamian adaptation, with traditional lyrics, but the rhyming, exchange of voices and "call and answer" techniques are unique to the Bahamas and a definite adcultrative component.

Many spirituals (mostly traditional) told about death:

"Swing low, sweet chariot,

Coming forth to carry me home."

or,

"In the sweet bye and bye,

We will meet on that beautiful shore."

or, they were expressions of the feeling of God in their bodies:

"Every time I feel the spirit,

Moving in my heart, I will pray."

Most secular songs, however, were linked to working songs, due to the

type of economy of the islands, e.g. fishing, farming, sponging, etc.:

"Hoist up the John B Sail,

See how the mainsails set.

Send for the Captain ashore,

Le'we go home. "

or for farming, e.g.:

"Watermelon is spoiling on the vine."

There were also songs that were very much like the calypso songs, composed extemporaneously to cite some local event of scandal, politics, superstition, love, sex and marriage. e.g. :

145

"There's a brown girl in the ring,

and she looks like a sugar in the plum.

or,

"Love, love alone, cause King Edward to leave the throne."

or,

"The Big Bamboo pleases one and all,"

or,

"Obeah don' work on me."

Tony MacKay sings a lot about Obeah:

"I came down on a lightening bolt, nine months in my mama's belly.

When I was born the midwife screamed and shout,

I had fire and brimstone coming out of my mouth,

I'm Exuma. I'm the Obeah Man."

Another song describing himself as the Obeah Man is:

"When I've got my big hat on my head,

You know what I can raise the dead,

When I got my stick in my hand,

You know that I am the Obeah Man.

If you got a woman and she ain't happy,

Come and see me for gamalame,

Take that gamalame and you make her some tea,

And she will love you all the time, and

When she got you running like a train on a track,

Take some flour and you make some pap,

That will give you strength in your back.

I've sailed with Charon, day and night,

I've walked with Hongamon,

Hector Hippolite,

Obeah, Obeah, Obeah, Obeah's in me,

I drank the water from the firey sea."

Folk songs and music are linked very closely to the dance, and like Junkanoo, there are definite African dances that exist but also many Euro-American dance music and rhythms.

Many aficionados of the dance like to categorize the various types into ten parts, viz.: amorous, ritual, rustic, carnival, street, topical, pursuit, square, finger snapping and handkerchief.

Katherine Dunham has three simple divisions that I will adhere to: sacred

(religious), secular

(folk) and social (popular modern).

"In the West Indies, the African drum beat, always in 2-2 or 4-4 time, predominates in any classification of the dance, whether it be a sacred voodoo ritual, simple folk dance in the country, a lascivious 'son' in a Havana Rhumba palace, or the grotesque phantasmagoria of African revelry during Mardi Gras." 10

10. LEAF, Earl, "Isles of Rhythm", A. S. Barnes & Co. New Yort. 1948, pg. 5.

146

In the Bahamas, the predominant African dances are Jump-In (or Fire Dance) and Junkanoo.

The following table attempts to categorize the folk dance and music of the Bahamas under the headings of (1) Religious, (2) Secular and t 3) Social:

(A) RELIGIOUS

(1) More purely African survivals

(a) Goombay

(b) Voodoo-Obeah (from the influx of Haitians)

(2) More Afro-Christian survivals

(a) Revival/Pentecostal

(b) Spirituals

(c) Funeral marching

(3) Euro/American traditional hymns

(B) SECULAR

(1) Work orientated

(a) Digging

(b) Fishing/boating

(c) Packing (e.g. tomatoes)

(d) Sponging

(e) Launching Songs

(2) More Euro-African

(a) Quadrille

(b) Heel and Toe Polka

(c) Rake and Scrape

(3) More Afro-Bahamian/Caribbean

(a) Junkanoo ("Rushing")

(b) Jump-In (Fire dance)

(c) Conch style

(d) Limbo

(e) Goombay

(C) SOCIAL

(1) More Euro-Bahamian survivals

(a) Ring Play

(b) Plaiting the Maypole

(c) Broom Dance

(d) Military/marching

(2) More American/Caribbean survivals

(a) Calypso

(b) Afro-Cuban (rhumba, bolero, cha! cha! mambo)

"Prior to the introduction of services for blessing

ships and sailors by the Bishop in 1839, there was hardly a sailor in

thee Bahamas who went to sea without putting on an obeah-string for his

protection against malignant evil spirits.”

PASCOE, C. F. "Two Hundred years of the Society for the Propagation

of the Gospel". 1701. London: The Society's Office. 1901, p. 225.

147

(c) Meringue ("Skulling")

(d) Jazz

(e) Bossa Nova(3) Present Day Popular Modern

(a) Rhythm and blues (soul, bump, getting down, funky, hustle etc.)

(b) Reggae

(c) Goomrock

(d) Electric Junkanoo

(e) Country and Western

(f) Rock

148