- Grand Bahama in 1887 from L. D. Powle The Land of the Pink Pearl or Recollections of Life in the Bahamas.

- Grand Bahama in 1891 from Stark's History and Guide to the Bahama Islands.

- Grand Bahama in 1917 from Amelia Defries In a Forgotten Colony

- Grand Bahama in 1924 from The Tribune Handbook

- Grand Bahama in 1926 from Mary Mosley The Bahamas Handbook.

- Grand Bahama in 1931 from Nassau and the Treasure Islands of the Bahamas

- Grand Bahama in 1934 from Maj. H. M. Bell Bahamas: Isles of June

- The Bahamas in 1964 from Benedict Thielen The Bahamas-Golden Archipelago

- rand Bahama in 1967 Moral Panic, Gambling. and the Good Life

Ten, Ten The Bible Ten : Obeah in the Bahamas

Dr. Timothy McCartney

Nassau: Timpaul Publishing (1976)

CHAPTER IV

PSYCHO-SOCIAL ASPECTS OF OBEAH

Man's subjective and object world are in constant inter-play and "nothing that he knows about the universe can be dissociated from the facts of his own life; and no product of his culture is so detached from the larger groundwork of existence that he can impute to his individual powers what alone has been made possible by countless generations of men and by the underlying cooperation of the entire system of nature."1

The Bahamian's beliefs and every aspect of his life-style and values are bound up or come under the influence of religious beliefs, superstitions and healing. It is reasonable to suggest, therefore, that Obeah finds its ramifications in every aspect of man's psycho-social development.

The Bahamas is a black country and the ethnic flavour of the Bahamas in terms of communication, communion and interaction, project (notwithstanding the contribution made by the minority groups) those images found in all countries in the Western Hemisphere where a majority or significant group of African descendents inhabit. African beliefs, rhythms, healing, although outlawed in many countries, rigorously repressed during slavery and discouraged by most of the colonial powers, still were kept underground and grew, in spite of the hindrances to expressions of religious ritual, folklore and local medical practises.

The historical development of the Bahamas indicates a strong suppression of African life styles. The majority Africans who came to the Bahamas with the Loyalists, were converted to Christianity and they, being mostly "house slaves," emulated their Euro-American masters.The minority Africans, either free or indentured, had more liberty in exercising their African practises, and these were the holders and retainers of the African life-styles. There were also some slave masters (who bought slaves at the auction at Vendue House) that were not too keen to expose their slaves to doctrines of "equality," and, so to avoid dissension and unrest, allowed their slaves to engage in their local practices. After emancipation, however, the established Church (Anglican) and the British colonial power discouraged "native" practises, and social restrictions were such that the Black Bahamian came to despise what he really had and, especially, if he wanted to reach economic and social prominence he had to be "cultured" or at least "act white." In spite of this racial-social-economic distance, only very mild legislation on the practise of Obeah was passed (see Chapter III) and there were no African religious or folklore practices that the ruling masters thought "dangerous" or "threatening" to them as, for example, Cumfa * that was banned in Surinam.

Until recently, the majority of Bahamians tried to forget or deny any roots with Africa, as part of the upward racial-social mobility. Many authors of Bahamian books confirm that hardly any link with African practises are retained. Craton wrote in 1962: 2 "Today in the Bahamas there are no names and few customs that can be traced back to Africa with any certainty." And Dr. Paul Albury recently wrote: 3 "In the Bahamas today, consciousness of racial distinction has almost totally disappeared among the blacks and because of inter-marriage, it would take a

1. MUMFORD, Louis, "The Condition of Man". Martin

Secker & Warburg Ltd., London 1944, Pg. 11.

* CUMFA: A dance ceremony in which the person becomes possessed and which

blood, in some ceremonies, is used. Cumfa is found mostly in the Guianas

and has its counterpart in "Kumina,” as found in Jamaica. The

only comparable ceremony of this type in the Bahamas is "getting

the spirit" as evidenced in the many Pentecostal church services.

2. CRATON, Michael, "A History of the Bahamas", op. cit. Pg.

188.

3. ALBURY, Paul. "The Story of the Bahamas". MacMillan Caribbean

(London) 1975

100

well-trained anthropologist to link any great number of them to their ancestral tribes. During slavery, however, the distinctions were obvious. Apart from physical differences, many spoke their native languages, followed their own tribal customs and took pride in their particular race. “

These ideas are, in part, in keeping with the ideas expressed by the brilliant West Indian author, Braithwaite, 4 who contends that "African culture not only crossed the Atlantic, it crossed, survived and creatively adapted itself to its new environment. Caribbean culture was, therefore not pure African, but an adaptation carried out mainly in terms of African tradition."

It is, perhaps, this ability of the African to adapt, to utilise their patterned life-styles and integrate it with imposed Euro/American religious practise that Obeah could flourish without the practitioners feeling too guilty about it. White magic beliefs fit in very comfortably with basic African beliefs about the supernatural world.

This chapter, therefore, attempts to view the development of religion, healing practises and folklore in the Bahamian context and give particular reference to Obeah and the reactivation of African practices or indigenous culture that is believed to be necessary if the Bahamas is going to retain any type of "identity." This is crucial, especially at this time to"new independence." There is an absence of a rich literary heritage, of very few meaningful architectural monuments and not enough older people around to instruct younger Bahamians in the cultural traditions of our ancestors.

The Bahamas and the rest of the Caribbean, being "hybrid" societies and class-differentiated entities are culturally tributary to their former colonial countries and geopolitically tributary to the strong presence of "big brother," the U.S.A. Cuba and Guyana appear to be the only countries in the Caribbean so far that have broken away from the U.S.A.'s political philosophy, and appear to have developed their own thing with the help of the neo/colonialist nation of Russia.

Bahamians (at least those who think) are becoming more and more concerned with the influx of the American mass media and its effect on our life-style as evidenced by the "Kentucky Fried Chicken-like mentality", the American accented 'hip' announcers of Z.N.S. that bombard the populace with one type of music and the negative influence of the self-defeating ghetto-like life-style of displaced-people'd Black Americans, as evidenced by the very poor taste black films. Bahamians—are terribly concerned about the pseud-sophisticated, "honky tonk "Burger-Kingian", "bastard", cultural image that they are now projecting. Yes, the search for cultural roots is more important now, than ever before.

SECTION I

OBEAH AND RELIGION

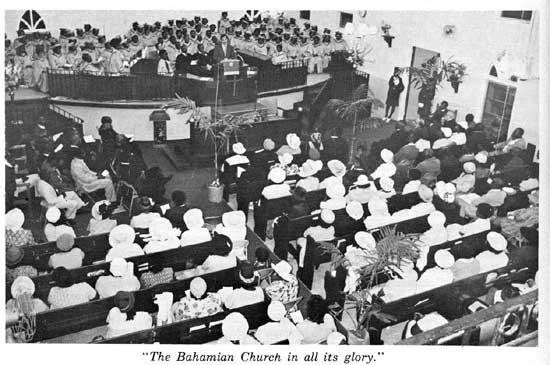

Visitors to the Bahamas, and natives alike, are unanimous about one fact - there are nearly as many churches in the Bahamas as there are houses and there are nearly as many preachers, priests, evangelists, pastors, brothers and reverends , as there are people - for such is the

4 BRAITHWAITE, Edward Kamau, "'The African Presence

in Caribbean literature". DAEDALUS. Spring 1974 (USA) Pg. 73.

* The "now" thing is for many local preachers to come up with

the title "Reverend Doctor" although some of them supposedly

obtained "doctorate" degrees from American Universities!

101

Kingdom of the Bahamas, a highly religious place! But, unlike the more racially cosmopolitan societies of Jamaica. Cuba and Trinidad, only orthodox (Roman Catholic and Greek) and Protestant religions co-exist.

There is little doubt that the world's oldest profession is not prostitution, as we would like to believe, but the religious specialist. This is the individual in any society who interprets or is the possessor of supernatural powers, derived, either directly from the original supernatural source, or ordained, appointed, apprenticed or studied into that state where revelation and interpretation are imparted to him. Religion then, is rooted in the mind of man and caters directly to man's psycho-social needs. Man is also a culture-bearing animal who never is and never can be alone and still remain human. "A peculiar organism, a man is the precipitated experience of many minds, reified knowledge, the word made flesh. The individual man, therefore, potentially lives as many millennia as his knowledge of the past can span. But it must be conscious and articulate knowledge, for otherwise a living man is partly the passive present-day residue of the pathology of past history, since tradition is, in part, as neurotic as any patient." 5

Religion, therefore, is the beliefs, behaviours and feelings of people. From time immemorial, man has been trying to understand himself and his God (or Gods) and even though ceremony, ritual, fetishes, symbols, saints, etc. differ according to the culture, there is striking religious similarity as found in "homo sapiens."

5. LA BARRE, Weston. "The Ghost Dance -Origins of Religion", Doubleday & Company, Inc., New York. 1970. Pg.XV "Preface".

102

It is generally accepted that the focus of African culture in the Caribbean was religious. Religion to the African was a total thing, and included his whole life-style, expressed in the African's art, beliefs, societal laws and references about the supernatural.

"The African religious complex, despite its homogeneity, has certain interrelated divisions or specialization ( 1) 'worship' - an essentially Euro-Christian word that doesn't really describe the African situation, in which the congregation is not a passive one entering into a monolithic relationship with a superior god, but an active community which celebrates in song and dance the carnation of powers/spirits (orisha/loa) into one or several of themselves. This is, therefore, a social (interpersonal and communal), artistic ( formal-improvisatory choreography of movement/sound) and eschatological (possession) experience, which erodes the conventional definition/description of 'worship'; (2) rites de passage (3) divination (4) healing and (5) protection. Obeah…is an aspect of the last two of these subdivisions, though it has come to be regarded in the new world and in colonial Africa as sorcery and 'black magic'. One probable tributary to this view was the notion that a great deal of 'prescientific' African medicine was (and is) at best psychological, at norm mumbo-jumbo-magical in nature. It was not recognised, in other words, that this 'magic' was (is) based on scientific knowledge and use of herbs, drugs, foods and symbolic/associational procedures (pejoratively termed fetishistic), as well as on a homeopathic understanding of the material and divine nature of man (nam) and the ways in which this could be affected. The principle of Obeah is, therefore, like medical principles everywhere, the process of healing/protection through seeking out the source of explanation of the cause (obi/evil) of the disease or fear. This was debased by slave master-rnissionary-prospero into an assumption, inherited by most of us, that Obeah deals in evil. In this way, not only has African science been discredited, but Afro-Caribbean religion has been negatively fragmented and almost (with exceptions in Haiti and Brazil) publicly destroyed. To properly understand Obeah, therefore, we shall have to restore it to its proper place in the Afro-American communion complex: Kumina—custom –myal—Obeah—fetish." 6

The Bahamian Plantation System has already been described in a previous chapter especially as to how it differed from the system in the other areas of the West Indies. The small population of slaves, most of whom were "house slaves" did not find it difficult to interiorize European Christian beliefs. The zeal with which Bahamian slave owners "converted" and treated their slaves, indicated to them (the slaves) that they were indeed lucky to partake of such benevolence. Then too, the Christian religion, which originally was High Church of England, appealed to them, even though they maintained many of their own beliefs.

Pascoe *. writes: "The greater number of the islands are peopled entirely by negroes, who, though normally Christians are to a great extent practically heathen. There are great difficulties in the work of evangelization, arising ( 1) from the population being scattered over so wide an area, the distance by sea from one end of the diocese to the other being about 650 miles. The people live in small settlements separated by great distances, some in huts hidden away in the bush, only to be got at by a weary tramp over sharp, honey-comb rock; others in settlements inaccessible except by boat, and then only in certain winds; others are secluded in the recesses of creeks to which the approach is almost blocked by clumps of mangroves. (2) The bulk of the male population is employed on the sea, sponge gathering during nearly the whole year. (3) Government provides schools (undenominationally) in the most populous centres. The

6. BRAITHWAITE. Edward Kamau.op. cit. notation on page

74.

* PASCOE. c.f. Two hundred years of the Society for the Propagation of

the Gospel. 1701-1900. London, The Society's Office. 1901. pp. 216-21.

103

Church, with the aid of grants from Bray's Associates and the Christian Faith Society does what it can to provide teaching of a very simple and elementary character for the children in the more remote places, but numbers are still out of reach of any school. The people generally are in a state of extreme ignorance, a large proportion being unable to read; witchcraft and other heathen superstitions abound, and immorality is everywhere very prevalent (4) The missionary clergy have to spend their time travelling from one station to another, and their field of work is so large that it is impossible for them, except at their headquarters, to spend more than a few days at a time at one place."

The appurtenances of the Anglican Church with its saints, altars, highly robed priests were not unlike African priests or the original Obeah man. Slowly, the slaves began to become totally familiar with the Jewish God and soon, especially after emancipation, he began to only retain what would be considered as "vestiges" of his original culture, on those official holidays that were in keeping with the Christian calendar.

The Bahamas, belonging to England, took on the aura of genteel English living. The minority whites ruled anyhow, and the British colonial officials with education, administrative know-how and zealous religious fervor, propagandised the Anglo-Saxon way of life - to the point that the displaced African and his descendants in order to survive and gain status had to become white, especially in his socio-religious behaviour. Except for sectarian revivals that came during the latter part of the 19th century, there has been no great religious movement or revival as experienced, for example, in Jamaica during 1860-61. This is not difficult to imagine as explained in our developmental history; however, it was strange that the African who depended on active participation and emotionalism, especially with drumbeating and emotive religious dance expression, adapted so readily to the more orthodox English church. Seaga 7 probably had an explanation when he wrote: "The Christian church in its orthodox and accepted form, frowns upon the more emotional manifestations of the spirit, and even if the fundamental division of exclusiveness and inclusiveness were somehow to disappear, a cultist would get little satisfaction in a service where his participation 1s restricted to hymn singmg and responses from a prayer book. Herein lies the second significant point of division: whether there is acceptance of the doctrine of spirit possession. From this dividing line, Christian groups are classified as 'temporal' or 'spiritual'. It is true to say that sects or cult groups which accept the doctrine of personal possession by spirit forces, classify themselves as 'spiritual' and correspondingly categorize those which do not as 'temporal'; the orthodox denominations all falling within the latter group, while spiritual groups include many Church of God and native Baptist sects such as Pentecostal, Four Square and others in addition to Revivalism."

There are no "cults" as such in the Bahamas, although the off-shoots of organised Christian Pentecostal religions are not much different in the Bahamas to Pukkumina or Zion as found in Jamaica. These fundamental religious groups in the Bahamas exhibit loud singing, "getting the spirit" (possession), speaking in tongues, the use of musical instruments (including percussion) in the Church (as opposed to just the organ or piano) and faith healing.

Even though the Church of England was the official religion, the Baptists have the earliest infiltration into the core of the Bahamian black population which brought appeal and acceptance to the blacks who needed this type of religion to cater to their basic African beliefs—a highly emotive type of worship.

7. SEAGA, Edward. "Revival cults in Jamaica. Notes Towards a Sociology of Religion", Jamaica Journal, Vol. 3 No.. 2. June, 1969. pg. 4.

104

Prince William was a freed slave from South Carolina who came to the Bahamas with other freed slaves in 1790 and was successful in attracting many blacks, at least more successful than the Rev. William Guy, who was sent to the Bahamas by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in 1731.

The Baptists, although divided into many "Conventions", are thoroughly indigenous in clergy and laity and have never endured racial division, because they are almost 100 per cent negro Bahamian.

“The first Methodist in the Bahamas was a negro, Joseph Paul, who came to Abaco from the Carolinas in the United States. He moved to Nassau in the 1780's and gathered a class of five, whom he taught in a parish schoolroom. In 1786, Joseph Paul founded a Wesleyan Church in the western district of Nassau. In 1794, the Methodist Episcopal Conference in the West Indies sent a man named Johnson to help Paul's society and a small wooden chapel was built." 8

The newly converted Methodists often suffered open hostility and persecution from the majority Anglicans, who thought that the new doctrines would have a disruptive effect on the negroes, especially when the question of "equality" came up.

Although the first Wesleyan missionaries preached with considerable success to the negroes, their doctrines were even more attractive to the native whites, especially of the poorer kind. As time went on, there came a noticeable social or racial division in the Methodist Church.

Bishop Bernard Markham, Anglican Bishop of Nassau and the Bahamas (1963-72) comments on the Church in the Bahamas, 9 "I think we are going to lose the young people of the Bahamas unless we can deal with this situation. It's 'churchianity" rather than 'Christianity.' " He continues 'the Church covered every part of life. Life on some of the Out Islands can be rather British. There is also a strange ambivalence, an ambiguity about the lives of people who are very proud of being a part of a church. They will come up to you, but they will live with a woman who is not their wife and get drunk every week. In some extraordinary way, I'm not we that the people in the Bahamas are associating the church with love, real love. Being a member of the Church is sort of a symbol of having arrived, rather than being Christian in their lives. There are certain strata of society. It would be difficult for those who are climbing socially to commit themselves in many of our churches. Being an Anglican is connected with colonialism here, you know. There are three hills in Nassau. One is Government Hill, one is Bishop's Hill (people don't talk about Anglican Hill, it's always Bishop's Hill) and there is Crazy Hill where, the mental hospital was. The three hills you see, not the seven hills At one time, the Anglican bishop had prerogative of mercy in death sentences, and it was always assumed that the Anglican Church went along with the government, because it was English. It was, for many years, socially respectable to be an Anglican. Then there came this extraordinary thing about 1860 and 1870, when a lot of Anglicans left the Church as they said it was developing in a very Catholic way. They found the Methodist Church as they said it was around the corner, and went across to Trinity Methodist. But I'm told that the real thing was that the Anglican Church was getting so many black people. Trinity Methodist has always been a refuge for white Bahamians. It still is, I think. On the whole, the two churches that have really integrated in regard to colour and race have been the Roman Catholic Church and our own

8. BARRY. Colman J. (O.S.B.), ''Upon 'These Rocks",

Catholics in the Bahamas, St. John's Abbey Press. Minnesota, 1973. Pg.

215.

NOTE: Not only is this book a highly researched one with regard to the

Roman Catholic Church in the Bahamas, but it has many "human insights"

into the Bahamian people that no other Bahamian history book so far, has.

I highly recommend this book for all Bahamians.

9. BARRY. C.J.. op. cit. Pg. 548.

105

Anglican Church. The Baptists are almost entirely black. The Scot's Kirk,.. well, we needn't take them too seriously, because I remember talking to a previous minister who said, 'Our Church has no mission at all. It has been here all these years. We never make any converts. We've never extended." Bishop Markham also commented on church building in the Bahamas. 10

"Church building, by the way, is a Bahamian trait. Bahamians like building churches. The largest Christian edifice is not St. Frances Xavier's, ** not Christ Church Cathedral ***, it is the Church of God Cathedral. We have Baptist Cathedrals here also. It's much easier to get people to come to build a church than to come to worship. Getting them to church is a problem, but getting them to build a church is wonderful!"

The Roman Catholic Church, that was firmly established in the large Spanish and French Caribbean colonies of Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and Haiti and which syncretised with Haitian African voodoo religion, was late in becoming established in the Bahamas. Fr. Chrysostom Schriener, O.S.B., a Benedictine from St. John's Abbey, Collegeville, Minnesota, was the pioneer of the Catholic Church in the Bahamas, and only attracted 77 converts in 1892. However 11 ,"selecting certain depressed islands, such as Cat Island+ and Long Island,++ and ignoring others, the Roman Catholics built beautiful churches, and the priests and sisters laboured heroically to provide educational, medical and social services so badly needed by the people. Their success was phenomenal and their new converts were attracted from all other denominations. The following table illustrates the proportional increase or decrease of the four major religious denominations in the Bahamas, from 1943 to 1953, taking into consideration a population at that time of 180,000:

| Denomination | 1943 |

1953 |

Increase |

Decrease |

| Anglican | 27.04 |

27.85 |

0.18 |

|

| Baptist | 33.85 |

32.61 |

1.24 |

|

| Methodist | 11.42 |

9.87 |

1.55 |

|

| Roman Catholic | 10.34 |

15.38 |

5.04 |

It is useful, at this time, to consider the religious groupings in present-day Bahamas:

(I) Orthodox Groups

Roman Catholics

Greek Orthodox

Jewish faith (Judaism)(II) Protestants

Anglican ( Church of England, Episcopalians)

African Methodist Episcopal Church (A.M.E.)

Baptists (many different "conventions", e.g. Southern, Central, Native, etc.)

* The Church of Scotland, the Presbyterian Church, which

was predominantly white, but now attractions many "middle" and

"higher class" blacks. It has been said that this is the newest

"in-church status symbol” at present.

10. ibid. Pg. 549650.

** Catholic *** Anglican ****Pentecostal.

11. CRATON. Michael, op. cit. Pg. 245.

+ Almost 100% Negro population.

+ + An Ethnically mixed island of majority "fair-skinned" Negroes,

with small "Indian" admixture.

106

Brethren (sometimes called " Holyrites" )

Plymouth

Exclusive

FreeChristian Scientists

Jehovah's Witnesses

Lutheran

Methodist

PresbyterianPentecostal Sects*

Church of God of Prophesy**

Assemblies of God

Church of God in Christ

Church of God of the Apostolic Faith

The Church of the Living God

Church of the Nazarene

etc.Salvation Army

Seventh Day Adventists(III) Eastern Religions

Black Muslims

Islam ( Moslems proper)(IV) Others

Mormons

Baha'is

Slutan-al-Azkar (or Divine Science of the Soul.

This is not a religion as such, but more a pathway that anyone can follow to get back to God.).International Meditation Society (organization which utilizes the method of transcendental Meditation and not a religion.)

Divine Light Society (Yoga)

Superet Brotherhood (obtaining the secret of Aura Science)

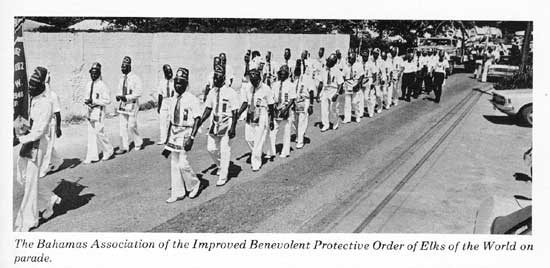

In addition to the many Christian denominations, the Bahamian is an inveterate joiner of organizations—"societies", "order", and “lodges". The reason for this being the Bahamian's basic African need to feel a part of and to discover means of solidarity and communication in social situations that he had been basically denied during slavery.

Although the socio-economic configuration of these organisational members have changed over the past twenty years, they attracted, originally, the black, lower socio-economic strata of Bahamian society. I stress lower - socio-economic strata because even the intellectual black Bahamian and those who had status in terms of family heritage, because of the socio-racial

* Many of the adherents of these sects are called 'Jumpers"

or "Holy Rollers" because when they get the "spirit"

they jump about and often fall to the ground and roll about. The majority

of Protestant sects are associated with a parent American association.

** This is the largest group of the Pentecostal sects.

107

system, hardly ever became affluent in relation to his Bahamian white counterpart. These black leaders were the leaders of the "secret societies" and the rituals were Euro-African orientated. Many of them were (are) prescribed in European manuals but the actual practises have taken on an African flavour. These "societies", "orders" and "lodges", although theologically in conflict with the dogma of orthodox and some protestant religious denominations, provide no basic conflict in the mind of the Christian Bahamian. With this in mind, the Christian-African spirit world and the utilisation of "spirits" for good or evil by the Obeah practitioner, presents no conflict to the Christian who believes in the efficacy of Obeah.

Let us briefly examine the African world of spirits.

The spiritual world of African peoples is very densely populated with spiritual beings, spirits and the living dead (called "Zombies in Voodoo terminology".)

These can be divided into

- Divinities

- associates of God

- ordinary spirits

- living dead

(a) Divinities and God Associates

These have been created by God in the ontological category of the spirits. These are in intimate contact with God and do His wishes

Some of these are national heroes who have been elevated and deified, but this is rare and when it does happen the heroes become associated with some function or form of nature, e.g. (a) the Ashanti’s have a pantheon of divinities known as “abosom.” (b) the Yoruba have one thousand and seven hundred divinities called “Orisa” associated with natural phenomena and objects as well as human activities and experiences. An example is "Ogun" the hunter, the owner of all iron and steel and the "chief" among the "divinities" and "Orunmila" the divinity who shows itself among men through the oracle of divination.

(b) Spirits

These are the common spiritual beings beneath the status of divinities and above the status of men. These are the 'common populace' of spiritual beings.

Spirits are invisible but may make themselves visible to human beings. They have no family or human ties with human beings, nor are they evil or good. Mbiti * states that with the spirits "death is a loss and the spirit mode of existence means the withering of the individual, so that his personality evaporates, his name disappears and he becomes less and not more of a person: a thing, a spirit and not a ma6 anymore. Spirits as a group have more power than men, just as in a physical sense the lions do, yet, in some ways men are better off, and the right human specialist can manipulate or control the spirit as they wish. Men paradoxically may fear, or dread' the spirits and yet they can drive the same spirits away or use them to human advantage.”

The majority of peoples believe that spirits dwell in the woods, bush forest, river, mountains or just around the villages. In the Bahamas the main abode is either the cemetery or the silk cotton tree.

* John S. Mibti "African Religion and Philosophy" Heinemann 1969 London page 79.

108

In Africa, spirits are very real to society, especially to those who have recently died. Various ceremonies are performed to maintain this contact, such as, placing food and other articles on the bier or by the gravesite, or offerings placed in spirit shrines. Such shrines belong to the community who share a common belief and are cared for by priests or the holymen.

(c) The Living Dead

These are the closest links that men have with the spirit world. The living-dead speak the language of men, and also the 'spirits' of God. They are people who have not yet become 'spirits’ or things when they appear to men or families, they know, have interest in what is going on in the family or community and may give advice or warn about tragedy in a family.

Thus the living dead appear to be partly 'human' and partly 'spirit.' They can either take direct directions from God or the human that they are in close contact with.

"*The Ashanti have spirits that imitate trees, rivers, animals, charms and the like and below these are family spirits thought to be ever present, and to act as guardians. Bambuti spirits are thought to serve God as 'game keepers,' and are described as small, dark skinned, bright eyed, white haired, bearded living in tree hollows and stinking. Those of the Ewe tribe are believed to have been created by God to act as intermediaries between Him and human beings. Although they are visible, people say they have human form, protect men, live in natural objects and phenomena and are capable of self propagation." The Fajulu believe that every person has two spirits ; one is good and the other evil".

No area of African-Euro Christian syncretisation is more evident in past and present day Bahamas as in the Bahamian way of death.

To the African, death and burial were a very important phase of man's life cycle.

"On the funeral depended not only the prestige of those kin of the deceased surviving him, but the safe journey and status of the deceased in his new abode in the spirit world." 12

* Ibid pg.87.

12. PATTERSON, O., "Sociology of Slavery", op. cit. Pg. 195-196.

109

"Man, we put him down good" is commonly used to express a good funeral. It is not surprising, then, that funeral rites of African slaves and their descendents in the Bahamas have survived more than most other cultural elements.

In Africa, burial is the commonest method of dealing with the corpse and different customs are followed. *

"Some societies bury the body inside the house where the person was living at the time of death, others bury it in the compound where the homestead is situated, others bury the body behind the compound, and some do so at the place where the person was born.

"The graves differ in shapes and in sizes, some are rectangular, others are circular, some have a cave-like shape at the bottom where the body is laid, and in some societies the corpse is buried in a big pot. In many areas it is the custom to bury food, weapons, stools, tobacco, clothing and formerly one's wife or wives so that they may 'accompany' the departed into the next world. Yet in other societies the dead body might be thrown into a river or bush where it is eaten by wild animals and birds of prey. In others, a special burial "hut" is used, in which the body is kept either indefinitely or for several months or years after which the remains are taken out and buried. In a number of societies the skull or the jaw or other part of the dead person is cut off and preserved by the family concerned, with the belief that the departed is 'present' in the skull or jaw; and in any case, this portion of the dead is a concrete reminder to the family that the person lives on in the hereafter. These methods of disposal apply mainly to those who are adults, or die 'normal' deaths. Children, unmarried people, those who die through suicide or through animal attack, and victims of diseases like leprosy, small pox or epilepsy, may not be given the same or full burial rites, but modem change tends to make burial procedures more even or similar for everybody.

"Again it is clear that people view death paradoxically: it is a separation but not annihilation, the dead person is suddenly cut off from the human society and yet the corporate group clings to him. This is shown through the elaborate funeral rites, as well as other methods of keeping in contact with the departed." Mbiti continues to summarise about the African way of death by stating that "death becomes then, a gradual process which is not completed until some years after the actual physical death. At the moment of physical death the person becomes a living-dead: he is neither alive physically, nor dead relative to the corporate group. His own sasa: ** period is over he enters fully into Zarnani + period, but as far as the living who know him are concerned, he is kept 'back' in the sasa period, from which he can disappear only gradually. Those who have nobody to keep them in the sasa period in reality 'die' immediately, which is a great tragedy that must be avoided at all costs."

The Bahamas Handbook gives a colourful description of Bahamian funerals: "Except for the band, which headed the procession, rendering 'Onward Christian Soldiers' with a particularly loud (but mournful) thump on the base drum, there wasn't a sound from the five hundred odd men, women and children in the funeral procession.

* Mbiti, John S. "African Religions and Philosophy

". Heinemann London 1969, page 158.

** Ibid page 150-152 .

+These are " time " periods as many African tribes conceptualizes

them. The 'Sasa' covers the now period and has the sense of immediacy

near-ness and now-ness. It is 'about to become', the process of realization

or recently expressed. Zamani is the period beyond which nothing can go.

It is the grave yard of time, the period of termination, the determination

in which everything finds its halting point.

13. Bahamas Handbook, "The Bahamian Way of Death", Etienne Dupuch,

Jr., Publications, 1970, Nassau, Bahamas.

110

"Walking solemnly in pairs; little girls in white with huge butterfly bows anchored to their pigtails and little boys in spanking clean shirts carried immense wreaths of plastic flowers. Following the women, in their white uniform dresses, marched a man carrying a lodge banner of one of the fraternal orders in the same bright colours as the men's sashes.

"Proudly, the banner-carrier, stepped out leading the lodge members who were making the last walk with their brother. A tightly-knit group of men in black, friends of the deceased and high in the ranks of the lodge, pushed the coffin.on a bier toward its final destination. The family—the widow and her small children—followed behind in isolation that nothing could touch.

"At the same time, coming up the hill on Cumberland Street, was another procession, also led by a band. But this band was jauntily playing 'When the Saints Go Marching In'. The people were dressed the same, but their lines weren't as orderly. In fact, there was a real strut to their step. And there was no bier. They had left that in the cemetery with the deceased, the anguish, the wailing and the family. The two processions passed on the hill of Cumberland Street just above the Sheraton British Colonial Hotel, one enveloped in a mood of heavy sorrow, the other on its way to a party.

"This familiar scene in Nassau is a ritualistic remnant of the original function of fraternal orders and burial societies in the Bahamas—the Elks, the Good Samaritans, the Masons, the Congo Society, the Volunteers,—the remnants of brotherly action in time of trouble forty or fifty years ago and earlier.

"In the days before there were morticians in the islands, the lodges and societies took charge of the funerals of members as a fraternal duty. In their poverty, the people banded together to help one another, not only in time of death, but also to lend a helping hand in time of sickness.

"When a member was mortally ill, the president appointed a couple of members to sit by the bedside with the family through the night, to give comfort and solace to the dying. After death (or "the passing"), two men, handy with hammer, nails and saw, were despatched to the lodge hall to build a coffin. A supply of lumber was always on hand.

"In the meantime, three men would be getting the grave ready, which on New Providence and on some of the other Bahamian islands is hard work, even today. A thin layer of topsoil covering limestone makes grave-digging a back-breaking labour of love and sorrow.

"Two or three women would be at the home of the deceased preparing the body for burial, which, due to the climate and lack of embalming methods, had to take place within twenty-four hours. Often, in those twenty-four hours, a wake was held, for with the small population of the islands, a lodge member would go to only four or five funerals a year. A funeral was—and, of course, still is—a meeting ground for old friends and a highlight in the social life. Everyone came to the funeral because it was a closely-knit inter-dependent community of people who shared the family's loss of a father, wife or child. There was no indifference at the time of bereavement. Even the children participated, as they do today, carrying, with solemn and innocent dignity, the wreaths of flowers to be laid on the grave side. No effort was made to soften the hard facts they were to face as they grew older.

"After motor vehicles came to Nassau, hearses were usually used—except in military funerals. But, today, there is a return to the old ways of rolling the bier.

111

"At Bahamian funerals, cars or not, people still walk in the funeral procession out of respect for the dead. Of course, another factor is that most churches are within walking distance of a cemetery if the interment isn't in the church yard."

Many of these lodges and societies began as African tribal self-help and self-identity institutions. Initially, there were the Congo Society, the Ibo Society, the Fulani Society and the Yoruba Society. Only the Congo and the Yoruba, at present, have adherents. but these are old people and, unless they are reactivated, they will die a natural death.

At the turn of the century, when British colonialism was making its presence known, there was almost an anti-African/native attitude that was subtly encouraged by the colonial administrators, Bahamian whites and the Afro-Saxon Bahamian. The prevailing attitudes and status symbols were white-orientated and local-native cultural symbols were regarded as "quaint", but "primitive", and something that no respectable-educated Bahamian would want to indulge in. British names, manners, music and customs were the aspiring goals, and so many of the "burial societies" or "tribal societies" went into American-orientated or Euro-orientated organisations that were most acceptable. For example, the Hauser Society reorganised and changed its name to the "Knights of King George Society." Another society, "The Bahamas Friendly Society" received its charter from William IV (who ruled the British Empire between 1830 and 1837). It also owned, for many years, a mace, a gift of William IV, which was an exact duplicate of the one used in the Bahamian House of Assembly.

Then came the Free Masons, a Euro-American institution that had "white" members who recognised their black Bahamian counterpart in handshakes and often gave help to their brothers, but would not allow their black brothers to join their particular group or meetings.

The General Grand Accepted Order of Brothers and Sisters of Love and Charity was founded in the United States in 1874, when a group of people gathered in Washington, D.C., and decided to form an organisation to take care of the sick and infirm, bury the dead, and help distressed members. This was before emancipation came to the United States.

In 1897, the Mother Lodge of Love and Charity in the Bahamas called "Pride of India" was organised.

Then, there is the "Scottish Rites of the Masonic Order" and, perhaps one of the largest organisations, "The Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks of the World". This organisation was founded in the United States in 1898 and caught on rapidly in the Bahamas.

"The regalia denoting the office of Elkdom consists of a gold chain worn around the neck with a golden medallion of an elk resting on his breast, and a special fez worked in gold thread." 14

There are many lesser organisations—Eureka Lodge, the Grand Lodge of the Independent Order of Good Samaritans; the Daughters of Samaria in the Bahamas, the Daughters of Ruth, ad infinitum.

The initiation ceremonies of most of these organisations are "top secret" and the various "signs"—the hand clasp, the placing of the feet, etc.,—may denote "friendship", "trouble", "asking for help," "identification", etc.

14. Bahamas Handbook. ibid.

112

The official uniform (or perhaps we should use the word "costume") consists of men with top hats, black suits, sashes or apron-like waistbands, bowties and, for the higher ranking "brothers" (or bills) or "daughters" (or sisters), emblems around the neck. No wonder that many members (especially men) fortify themselves with alcoholic drinks (mostly rum) to withstand the intense heat generated by their black bodies and black clothing.

The ceremonies around the grave, after the normal "Christian" or "official ceremony", are colourful by their singing, various "signals" with their hands and arms, e.g., in unison they would outstretch their arms, clasp them to their breasts three to four times, then in unison, they would respond to some readings, either from the Bible or their manual book; then they would grasp the green leaf or foliage that had been pinned to their lapels (or pinned to their hats) and, in one last gesture, throw it in the grave of the deceased.

These organisations, with their dress, marching and ceremony, add to the colour and tradition of Bahamian blacks. They take their "lodges" very seriously, and keep up the payments of dues so that when they die, they can be "put away in style"!

Thus, Bahamians of African descent, with the elaborate funeral imbedded in their psyche, have made colourful adaptation of Christian burial where no psychological conflicts exist, as they combine solemnity with "festival”.

Many Obeah practitioners are lodge members, and belong to organised religion. Their healing powers are in keeping with the legitimate church where "faith" healing and prayers for the sick cause no conflicts.

The "speaking in tongues" based on what happened in ancient times on the "Day of Pentecost" is legitimized in the incantation or the gibberish-type language that the Obeah practitioner may utilise.

Casting out demons of those possessed, cause no Obeah-theological conflicts. After all, the Christian church recognises the spirit world 6f good and evil—so does the Obeah practitioner.

The Bible relates the story of Jesus casting out demons and healing the sick. The Obeah practitioner is in command of the spirit world, and healing the sick is his forte.

To the Bahamian Pentecostals, the supernatural world resembles the natural one. There are rivers, lakes, mountains—"Jordan river is chilly and cold" is the theme of a favourite spiritual, and "crossing the River Jordan" is passing through to a place of rest "on the other side.”

Thus, Obeah and religion are integral forms and are unified in magico - religious behaviour, and have deep psycho-social and psycho-physiological implications.

The phenomenon of "getting the spirit" is the religious term

for being imbued with the power

of God.

The phenomenon of being "possessed" has the connotation of being under the influence of the Devil or evil forces. The individual who is possessed can either be an evil person who has "sold his soul to the Devil" or an individual who has been fixed by Obeah. Only the Obeah practitioner, or a religious man (priest, pastor, etc.) utilising the power of God through "Exorcism" can release the individual from these powers.

113

On the other hand, "getting the spirit" is a condition that every Pentecostal Christian strives towards. his is a sign of having the "Grace of God" within you, letting the Holy Ghost (Spirit) rule (temporarily) your mind and body. Being saved, baptized and filled with the Holy Spirit ("Sanctified") is the prime goal of Protestant Christians.

A more descriptive account on "possession", "exorcism" and "having the spirit" will be given in the following section on Obeah and Medicine.

One of the most popular manuals used by the Obeah practitioner is "King Solomon's Guide to Success and Power". On its cover is found the following quotation from the Bible (Mark 11,22-24):

"And Jesus answered, 'Have faith in God. For verily I say unto you, that whosoever shall say unto this mountain, be thou removed, and thou cast in the sea, and shall not doubt in his heart, but shall believe that those things which he saith shall come to pass, he shall have whatsoever he saith.' "

We can see, then, faith (the song popularised by the late, great Nat King Cole, "Faith Can Move Mountains") as a legitimate belief, finds its credence in the Bible, by which the religious specialist and the Obeah specialist both get their "directions" and "power" by which they interpret, advise, edify and heal.

114 (to end of section)