- Grand Bahama in 1887 from L. D. Powle The Land of the Pink Pearl or Recollections of Life in the Bahamas.

- Grand Bahama in 1891 from Stark's History and Guide to the Bahama Islands.

- Grand Bahama in 1917 from Amelia Defries In a Forgotten Colony

- Grand Bahama in 1924 from The Tribune Handbook

- Grand Bahama in 1926 from Mary Mosley The Bahamas Handbook.

- Grand Bahama in 1931 from Nassau and the Treasure Islands of the Bahamas

- Grand Bahama in 1934 from Maj. H. M. Bell Bahamas: Isles of June

- The Bahamas in 1964 from Benedict Thielen The Bahamas-Golden Archipelago

- Grand Bahama in 1967 Moral Panic, Gambling. and the Good Life

An Informal History of the

Grand Bahama Port Authority,

1955-1985

The following article was written at the suggestion of Chris Lowe of the Grand Bahama Chamber of Commerce. He was concerned that there was no available history of Freeport's origins and development available online, and felt that this was something residents of the community ought to have access to. After reading the selections posted on this website, he got in touch with me and, by providing useful source material, convinced me that this was a worth-while project. It will be a while before it is complete, as the later years are as yet far less well documented than the earliest and more dramatic ones.

As in any historical reconstruction based on available but hardly complete (or unbiased) sources, the "Informal History" inevitably will contain errors and omissions. There may also be some facts and interpretations that are unwelcome. If you the reader can correct the former, by sending me an email (jimwbaker@comcast.net), I would greatly appreciate it. I do not however guarantee to accept or credit corrections unsupported by more than mere assertion, so please cite sources or detailed circumstances wherever possible.

Part Two: Freeport Begins

Daniel Ludwig

The first task that the Port Authority faced was the implementation of the stipulations set down in the Hawksbill Creek Agreement, and that required money. Wallace Groves sought out investors who would underwrite the construction of the harbor and support facilities within the required three year period. He was fortunate in being able to secure the cooperation of one of the world’s wealthiest men for the construction of the harbor facility, American shipping magnate Daniel K. Ludwig of National Bulk Carriers, Inc. D. K. Ludwig (1897-1992) became one of the world’s first billionaires through his development of the modern supertanker and in the refinement of coal, oil and mineral resources (as well as real estate, banking and Argentine cattle). In 1951, Ludwig leased the Imperial Japanese Navy shipyards at Kure, where the massive World War II fleet had been built, for a nominal sum, and began constructing his huge vessels. Apparently the Japanese became dissatisfied with the deal and were attempting to renegotiate the terms of the lease at the time Groves was looking for a way to build his harbor. Ludwig announced that he was considering moving his operations to Grand Bahama, and invested $2 million in preparing the Hawksbill Creek harbor in exchange for 2,000 acres of the Port Authority’s industrial land.

It seems in retrospect that Ludwig probably had no intention of moving his vast operations, but the threat worked and he was able to negotiate the continued use of the Kure Shipyard, whereupon he sold his interest in the Port Authority harbor to U.S. Steel. Ludwig not only recouped his investment but also acquired additional acreage and established the King’s Inn (later, the Bahama Princess, as one of his chain of Princess hotels and resorts). He also appears to have been involved with the development of the International Bazaar. The steel company established a subsidiary called Bahama Cement, Ltd., which got a 12-year monopoly on cement production in the Bahamas in 1962 and also undertook to dredge the harbor to 42 feet; deeper than New York harbor.

Another Port Authority success was the Freeport Bunkering Company. Built with a $1 million loan from Gulf Oil in 1958, the company opened its oil depot just before a fortuitous change in U. S. law in 1960 made it profitable to transport oil from Freeport to U.S. ports. Not all early enterprises succeeded, however. For example, Bahamas Seacraft built a huge warehouse only to abandoned it, while other concerns simply disappeared from the record. By 1960, there were only 30 or 40 licensed companies, some quite small. Groves was not going to be able to keep up with his commitments unless further investment could be found. Nothing daunted, Groves approached the Bahamian government in April, 1958 for yet another huge area of Grand Bahama under a ten-year conditional lease that required him to spend an additional £1 million in development. The second acquisition, approved by the government in May, was for 40,000 acres at the same £1 an acre. A survey showed that the acreage in question was actually 78,727 acres, but Groves received 88,402 at the agreed price, and eventually the entire property totaled 145,566 acres, almost 230 square miles of the island’s entire 530 square miles.

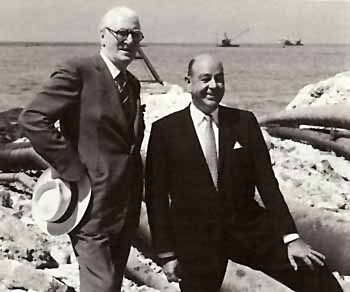

Sir Charles Hayward & Wallace Groves

Two significant investors that came on board in July, 1959 with the permission of the Bahamian government were Sir Charles Hayward (1892-1983), whose “Variant Industries. Ltd.” acquired a 25 percent share in the Port Authority for £1 million (then $2,800,000), and Charles Allen of Allen & Company of New York, who introduced a consortium that bought another 25 percent share for slightly more than £1 million. Sir Charles Haywood began his career as a engineer before World War I who undertook the manufacture of motorcycle sidecars for the A. J. Stevens (Motorcycle) Company in 1913, but left the business to become a stockbroker in 1928. He eventually became a millionaire and founder of the Firth-Cleveland Group of industries, which he sold in 1970. With Sir Charles came his son Jack, who would devote his life to Freeport and the Port Authority project. Charles Allen (1903-1994), on the other hand, was an American financier with the small “boutique investment bank” of Allen & Company, founded by him and his brother Herbert in 1922. As an advisor to the Duke of Windsor, Mr. Allen presumably had earlier Bahamian connections. Allen & Co. at the time had controlling interests in steel, shipbuilding, chemicals, drugs, insurance and other industries, but it was also becoming heavily involved in the media and entertainment business. Their biggest success in the early 1960s was the pharmaceutical company Syntex, which Allen & Co. acquired in 1956, a Mexican-based pharmaceutical firm that specialized in making synthetic hormones from yams. Syntex opened a branch in Freeport in 1967, and became the third substantial corporation to locate in the Port Authority area. Allen & Co. sold Syntex in 1994 to Roche Holding Ltd. for $5.3 billion, and the former 102 acre Syntex site on Grand Bahama was acquired by the South African PharmaChem Technologies in September 2003. The shareholders as of 1 December, 1959 were [Block 1998:53]:

Shareholders |

Shares |

Description |

Wallace Groves |

96 |

Dir. & Chair of Board |

Georgette Groves |

35,001 |

|

Abaco Lumber Co. |

964,900 |

A Groves company |

Variant Industries, Ltd. |

505,000 |

A Hayward company |

Charles Allen |

252,500 |

|

Athur Rubloff |

71,428 |

A Chicago-based real estate agent |

C. Gerald Goldsmith |

85,822 |

An officer in the New York Cosmos Bank |

Evelyn J. Lubin, Trustee for Barbara Lubin Goldsmith |

31,750 |

|

Evelyn J. Lubin, Trustee for Ann Lubin Goldsmith |

31,750 |

|

Alfred R. Goldstein |

31,750 |

Engineer |

Groves now only held a 50 percent stake in the enterprise, but he remained the man in charge. The partners also agreed to the government’s request to underwrite a thorough scientific survey of Freeport’s potential economic, social and topographical possibilities. They commissioned the Department of City and Regional Planning at the College of Architecture, Cornell University, to do this. The study was published in the fall of 1960. In their historical overview, the report recognized a problematic precedent to the Freeport venture:

Bahamian merchants had long indulged in the little known sport of trapping foreign investors, deluding them by the lure of a perfect climate and tax-free business possibilities, into dropping thousands of dollars into various operations only to coyly ensnare them with the net of legal red-tape, thereby forcing them to sell out at substantial losses. The islands have, historically, been a closed corporation and islanders have, traditionally, done business only with fellow islanders. On the small islands and cays which are privately owned, guests come only by invitation and for an outsider it was, and still is today, virtually impossible to capitalize on the vast opportunities that await the enlightened investor without the cooperation of the islanders themselves. After the war, with growing concern as to what the islands should do to revitalize their economy, the climate from the business point of view, became right for foreign investors for the first time in Bahamian history. [Cornell 1960:11]

This shift was due in large part to Stafford Sands and like-minded individuals among the Bay Street Boys, who, despite a well-deserved reputation as the Bahamian equivalent of the Bermudan oligarchy known as “The Forty Thieves”, concluded that it was in their best interests, as well as those of the colony, to encourage long-term investments that could only come from confident foreign investors rather than jump for the quick buck as they had in the past. Still, short-sighted island insularity (often masquerading as Bahamian patriotism or racial loyalty) was far from dead, as future events demonstrated.

As the development of the huge tract of land was not progressing quickly enough, a significant shift of emphasis was initiated—tourism and private residential development were added to the package. Sands, who headed the very effective Development Board for tourism from 1949 (before he became the Bahamas Minister of Finance and Tourism in 1964 when the Bahamas became internally self-governing) suggested a tourism initiative early on but was vetoed by Groves. As Sands explained, “Mr. Groves was not interested in the tourist trade. He did not consider it stable. I was a tourism man, and he was an industry man.” [Messick, 1969:53] The desperate need for growth convinced Groves that the development of leisure facilities and tourist attractions were in fact necessary, and led to the first important amendment of the Hawksbill Creek agreement in 1960. This realization very well may have been the impetus for the additional 1958 acquisition of land, to provide a venue for the new intiatives apart from the original industrial zone.

Whatever the sequence, Groves began negotiations with the Bahamas government on an amendment to the original agreement that was approved on 11 July 1960. It should be noted that, as the 1960 amendment required the approval of all of the licensees, the GBPA spent a considerable sum “buying” these votes, and even more on the subsequent 1966 amendment that only required four-fifths of them to agree. The amendment began by recognizing that the conditional specifications in the 1955 Agreement had been met, and then agreed that “other businesses and enterprises” should be added to the industrial objectives.

One of the first decisions that had to be made was whether or not it would be feasible to plan an industrial complex and whether such a complex would negate the possibility of creating a resort area on the island. [Cornell 1960: 29]

The new boundaries of the Port Authority territory were specified as from three and a half miles west of the west bank of Hawksbill Creek to 500 feet east of the east bank of the mouth of Gold Rock Creek, and various details concerning education, medical services and building standards were clarified. One particular addition was the construction of a first-class, deluxe resort hotel of not less than 200 rooms. The acceptable enterprises now included the Port Authority “owning, constructing, operating, and maintaining hotels, boarding houses, clubs (resident or otherwise), apartment houses, restaurants, marinas, yacht basins, and places of entertainment (other than cinemas), sport, amusement or cultural activity.” [Hawksbill Report II 1971:38]. A significant and obviously necessary change was making it necessary to have only four-fifths of the licensees agree to future changes, or to transfer “rights, powers or obligations” from the Port Authority to a future “local authority”.

The immensely increased level of development was made possible by the contribution of yet another new investor, the flamboyant Canadian financier, Louis Chesler. Up until this point, the Port Authority, while aggressively ambitious on paper, had been relatively conservative in its leadership. Groves, despite his checquered past that would be brought up whenever things seemed questionable, worked hard to establish a permanent and stable community with a secure future. Freeport was no fly-by-night scheme or stock manipulation swindle. Hayward and Allen, while willing to assume high levels of speculative risk, were both reputable and sound business men. Chesler, on the other hand, was quite a different sort of personality. His contribution, which proved both crucial and perilous to the project, led to the disputes that have overshadowed Freeport ever since. We will consider “Uncle Lou’s” casino initiative and its fallout later on, and focus first on the $12 million infusion of cash Chesler was able to bring to the table in 1960 (officially in 1961).

Louis Chesler

Louis A. Chesler, born in Belleville, Ontario in 1913, made his first million through Canadian mining stocks such as Loredo Uranium Mines between 1942 and 1946, before shifting his base of operations to Miami, Florida. Using the same sort of “corporate shell” financial shenanigans that had brought Wallace Groves low, he parlayed his way to control of several corporations. The General Development Company, for example, was involved in the infamous “Florida land deals” of the time, but it also constructed actual developments at Port Charlotte, Port Malabar, and Port St. Lucie, and was perhaps a model for what was to follow in Grand Bahama. However, it was the theatrical corporation that Chesler controlled, Seven Arts, that would play the primary role in the history of Freeport.

Seven Arts, founded in 1958, was a motion picture production and distribution firm that bought the rights to various old movies and cartoons. Chesler and his partners, who had engineered the purchase of the Warner Brothers pre-1948 film library in 1956, bought a controlling interest in Seven Arts. Chesler became chairman of the board of Seven Arts and its largest stockholder, and acting in this role, pressured the company into investing $5 million in a quite different venture, the Grand Bahama Development Corporation (Devco). Another $5 million was extracted from Loredo Mines, and to complete the needed $12 million, Chesler secured a loan through a New York bank (the actual cash came indirectly from Seven Arts). For this investment, the new Grand Bahama Development Corporation received 102,305 acres of Port Authority land in 1961, which in time became “Lucaya”. Half of Devco stock was issued to the Port Authority, with Seven Arts (Bahamas) and Loredo Uranium Mines receiving 20.75% each and Lou Chesler personally acquiring 8.5%. The whole thing was observed to be rather irregular at the time, but “counsel for the Port Authority”, i. e., Stafford Sands, ruled that everything was on the up-and-up, and so the matter rested.

It is unclear exactly how and when Lou Chesler arrived on the scene. According to Sands, Chesler “appeared out of the blue” one day in Nassau, and Sands forwarded him to Freeport. With his Florida development connections, Chesler certainly was aware of the Freeport project. However, there was also a curious link with Charles Allen, who with his partner Serge Semenenko, had bought a lot of stock in Warner Brothers and reorganized the company in 1956 just before the sale of the studio’s backlist films to Seven Arts.

The design for the new and expanded Freeport community was worked out in principle in the Cornell University study, which became the basic plan for the future. Although some of the details appear to contradict each other (especially in the rather fuzzy diagrams and pictures of models), the general layout of the community is what exists today:

Because of the port facilities, the industrial area was logically placed at Hawksbill Creek and the west side of the creek was preferable because the prevailing south-easterly winds would blow away the noxious odors, noises, etc. We decided to center the resort activities around a marina which could be dredged from the low-lying areas near the middle of the Freeport holdings. The City of Freeport was located midway between these two areas, where it would be most convenient to both, as well as to the airport. [Cornell 1960:30]

Once the tourism initiative was approved, work began on the new plan and on the hotel, which had to be completed by the end of 1963 (the Lucayan Beach hotel, which opened New Year’s Eve, 1963).

The first step was to install the infrastructure for the new Lucayan development made possible by the Chesler investment in Devco. In 1960, tourism was almost entirely limited to the very rich with their freedom of movement and self-contained resources on yachts, as had been the case for many years throughout the islands (that Groves’s Regardless voyages demonstrated). The Cornell researchers noted this, and also the need to attract another level of customer:

Although Freeport is fast becoming a major tourist attraction in the Bahamas – second only to Nassau, it is said – still the variety of types of tourists who go there is somewhat restricted. Although an increasing number of “Upper-middle” and “Lower-upper” economic class Americans spend from two days to three weeks enjoying Freeport’s hotel accommodations, the main bulk of tourists still are very, very wealthy – usually men who come from Florida or New York or Pennsylvania on their private yachts, alone except for a skipper and crew to cater to their wishes, and who stay on their yachts, using Grand Bahama’s fertile waters for game fishing and none of her other facilities.It will certainly be necessary to encourage a larger volume of tourist traffic to the island to develop its full potential and this essentially will mean tapping the supply of lower-income tourists who are becoming increasingly mobile and will provide the major proportion of any boost in visitors’ numbers. [Cornell 1960:27]

New hotels and private estates required roads, harbor facilities and other amenities, all of which needed to be made ready in record time. For the yacht-less, there was only the Caravel Club, an eight-unit guest house later expanded to 25, which had a small restaurant attached. It is unclear what the report was referring to in the matter of the upper-middle and lower-upper visitors, as there weren’t many facilities for them to stay for their “two days to three weeks”, but presumably they knew of what they spoke.

The airport opened in October, 1961, and was soon enlarged. The East Mall, Freeport’s first “highway”, was built in 1962 and the harbor at Lucaya dredged out of a marshy area on the south coast in 1962/63. Sixty miles of roads were built between 1955 and 1963. Considerable progress was made on downtown Freeport, including the first supermarket (now defunct), police stations, post office, the Freeport Hospital, the Mercantile Bank building (which later housed the Port Authority offices – the first Port Authority headquarters became first the Magistrates’ Courts, and then a police station. It was subsequently demolished, although Edward St George had hoped it could become a “Freeport Museum”), and the Anglican Church as well as schools such as Mary, Star of the Sea. There were 175 licensees by 1963, and a number of smaller businesses and shops. The Coo-Koo-Roo restaurant opened in 1962, and movies were shown at the Sports and Social Club. Plans for “Hong Kong West” (the future International Bazaar) were announced in 1963. The Queen’s Cove development (recently overcome by a series of hurricanes) was the first independent subdivision, followed closely by Caravel Beach (near Ranfurly Circle and not to be confused with the beach of the same name near where the Xanadu is today), Royal Bahama Estates west of Coral Road, and Bahama Terrace, whose canals were dredged in 1964. Peter Barratt, who wrote the authorative history of Grand Bahama, was hired as Freeport’s urban planner in February 1965.

Freeport—billed as “The New World Riviera” by Devco—was new, exciting and slightly exotic, with promise of great things to come. The company’s plan for land sales and settlement (sometimes overlooked in the emphasis on ephemeral tourism) was laid out in a 1964 publicity flier, which is worth quoting at length, as it was to have lasting repercussions. After a number of pretty photos (almost entirely of white residents) and descriptions of amenities, the flier closes with:

To take full advantage of Lucaya’s dynamic potential…for yourself and your family…the time to act is now! The key to the entire concept of Lucaya is the emphasis and dedication to careful and professional planning by a firm whose experience in the field is vast and whose energy and sincere efforts are resourceful. Everything that has already been done and is planned for Lucaya is designed to make it inviting to come to, desirable to live in, and interesting to invest in.

Land has permanence…solidity. The value placed on a good piece of land increases as demand increases and supply decreases. Land is scarce where climate and accessibility can afford you comfortable, easy living the year ‘round, and an opportunity to “live abroad”—yet be so physically close to the U.S. mainland.

By 1980, seventy nine million more Americans than there were in 1960 will be looking for their share of man’s greatest possession.

Lucaya is an area which may grow at an even faster rate than Florida’s real estate explosion. 1961 drew 368,211 visitors to the Bahamas; 1962 had 444,870 tourists and 1963 counted a total of 546,404 persons—an increase of 67% over the last two years!

Many of these visitors are looking for land investment, retirement land and permanent residence land.

It is a well-known fact that desirable and accessible resort residential real estate is diminishing. Now is the time to take advantage of the opportunities offered in Lucaya…where there is still room for capital growth…expansion…gracious living.

“Island Living” in Lucaya, Grand Bahama, opens to a new chapter in human endeavor…combining the vitality of growth with the casualness of semi-tropical living. To build a way of life while enjoying nature’s and man-made advantages. To enjoy uncrowded living with the ease of travel to populated areas. To invest in the first major island you reach after leaving Florida’s shores. To invest in an area where millions of dollars have already been spent for its growth and expansion.

We urge you not to be one of those who may regret and say, “Why did I wait so long!”

“The New World Riviera” LUCAYA

However, even as Devco was successfully promoting its properties, another venture was in the works that would overshadow all the other elements in the Port Authority-Devco folder—casino gambling.