Some Old Plymouth Ropewalks

By Fred A. Jenks

Plymouth Cordage Notes vol. 1, No. 3 June 15, 1925

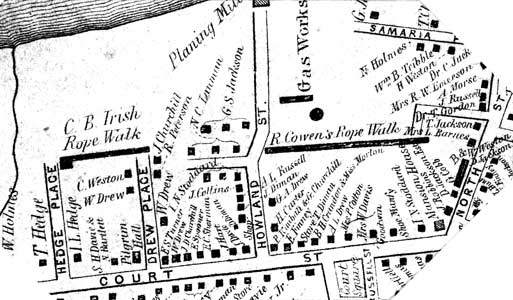

(Irish and Cowan Ropewalks, 1858)If, sixty years ago, you had passed thru the narrow way near the Mayflower Tea Room on North Street and thru their back yard, you would have been confronted with the open door of the head house of what was once Cowan’s Rope Walk. The writer can well remember the big wheel that stood right in front of the door. The Rope Walk was an old rope walk at that time and there was no large rope made, if, indeed, there was ever any rope of great size made there. If you had gone a little further down North Street and passed down Gordon Place, and turned to your left, you might have seen Capt. Luther Ripley and his old white horse, walking in a circle, producing the power for the Rope Walk. In those days, little was made there except clotheslines, fishing lines, spun yarn and other tarred fittings. But it was the Tar House that required the power furnished by Capt. Ripley’s horse.

The writer well remembers Deacon Faunce of Chiltonville, much younger than he is now, when he was an employee at the Rope Walk as well as his uncle. I think the family might have been classed as a rope making family. For in those days, families engaged in rope making as can well be illustrated by the Cowans, Faunces and Dimans of Plymouth, the Fredericks of Salem, the Maines of Marblehead, and the Walls of Hingham.

The business of this Rope Walk was, of course, mainly to equip the fishing fleet of Plymouth at that time, for in those days, fishing and coasting vessels were numerous in the harbor of the old Town, The Fall of the year showed what seemed to the boys, a perfect forest of masts, vessels laid up for the winter. Hundreds of vessels of New England engaged in the mackerel fishing made port here at night. Cowen’s Rope Walk extended through to Howland street.If you had cross Howland street you would have found the Head-house of another Rope Walk, owned by Chas. Irish, and this Rope Walk ran to the “right of way” which now runs between the Villa Maria and the new Town Hall. Brewster street, at that time, was not laid out, and Chilton street ran to a dead end at the Rope Walk. The house now occupied by Mr. John W. Churchill, being the last house on the street.

The principal work done in Irish’s Rope Walk was what the ropemaker in those days knew as “white work.” He made large quantities of cotton rope of small size for fishing lines, mackerel lines and other fine work, spun yarns and other tarred fittings, small hemp rope, 6, 9, and 12 thread as well as hand lead lines, deep sea lines and ordinary manila and cotton clotheslines which were put up in hanks by hand.If ever men worked amid pleasant surroundings, it was the Ropemakers at the old Irish Ropewalk. The long, low building, on the east side an unobstructed view of the inner harbor and beyond to the bay. On the west side the well cultivated gardens on the east side of Court Street and the large elms tempered the afternoon/

Continued on Page 3.sun. the whirring of the wheel was a pleasant sound mingled with the songs of the old spinners as they slowly worked away from the wheel, spinning their thread. An the boy who had been in swimming at the shore and had wandered up to the Ropewalk to perhaps visit his friend, experienced the dull and drowsy feeling of complete contentment.

Plymouth Cordage Notes Vol. 1 No. 5 Aug. 15, 1925

Old Plymouth Ropewalks

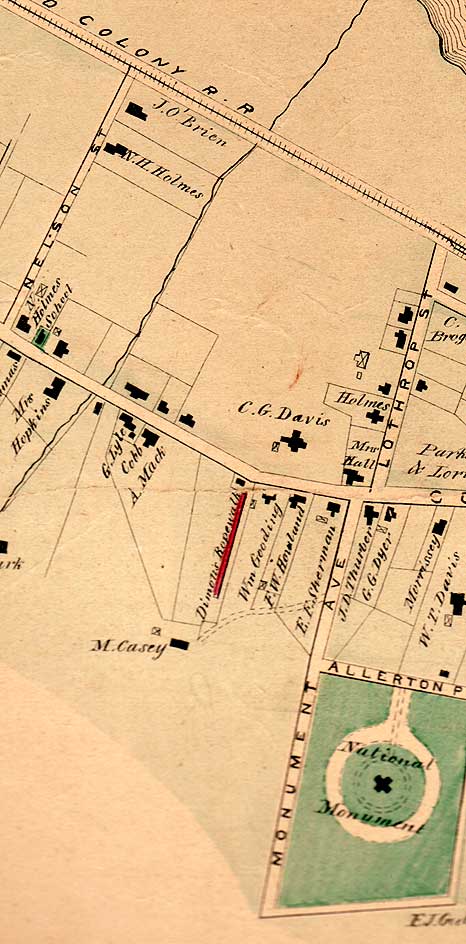

(Dimon's Ropewalk off Court St., shown in red, )Diman’s Ropewalk

Another ropewalk, once in active operation in Plymouth, was Dimans’s; very small, not more than 300 feet in length, equipped with hackles and spinning wheels, no power machinery of any kind.

If running full, ten or twelve men and three boys would be a full compliment of help. This walk was situated in the field on the west side of the road as you ascend the Cold Spring Hill, the westerly end near Wood Lane, now Alden Street, just about where the schoolhouse now stands. It was one of those small ropewalks found in almost every seaport of town in the early days, and provided work for the owner and a few of his neighbors, No rope larger than clotheslines, bed cords and twine were ever made, and much of this work might be classified as remade rope.

This writer had his first experience in ropemaking at Diman’s. Mr. Diman sometimes purchased old manila bale rope and would hire boys to carry this old rope to their homes, untwist the strands and then open up the yarn on a loper. It was also some job to carry these heavy bags of old bale rope and the opened hemp from the vicinity of the Training Green to Cold Spring Hill by wheel-barrow. Ropemaking might have been a simpler operation than at present, but transportation was more difficult.

It was good hemp, long and soft, a light yellow in color due to the whale oil used in the preparation of the manila fiber. The writer can well remember the caution given not to leave any bights in the fiber and to the careless boy who left a bight in the fiber which, when it got in the hackle, broke off the hackling pin, which, flying past the hackler’s head, stuck in the wall of the Ropewalk.

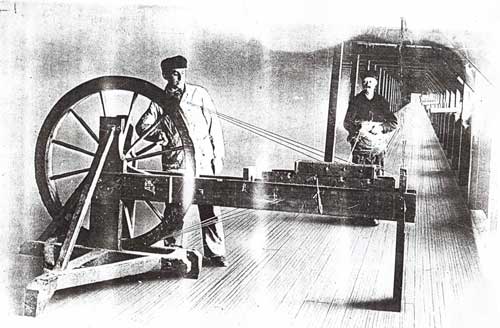

(Wheel boy and Spinner, Plymouth Cordage Co., 1904)Clotheslines and bed cords were not always of manila. Short pieces of old tarred ropeyarns were run in and covered by the hemp. The spinner not only had his hemp about his waist, but also carried tucked into his belt, the bundle of tarred yarns which he covered with fiber which were then made into a rope. It looked well, and was strong enough for the work demanded of it. It was a rope of such construction as this, shoddy work if you will, that many years later played a part in the breaking of a patent for the making of binder twine by covering a jute thread with manila fiber.

You would think that to spin a yarn by covering short pieces of tarred yarn with hemp would be busy work and require more than one pair of hands; but in addition to this, the spinner sometimes hove his own wheel. Spinners, usually two or three, with a wheel boy to furnish power constituted a gang for a spinning ground but in Diman’s Ropewalk they had what was called a tommy wheel. It was run by an endless band of rope passed around the spinning wheel, and then around the pulley with a counter-weight at the end of the ropewalk, and the spinner hitched this transmission rope to his belt and turned his own wheel as he walked down the ground, spinning his thread. When business was dull, he got along without a boy. And again, this capable old spinner, when he was spinning yarn with good, well prepared stock would spin two threads and still heave his own wheel.

The gang of spinners with the wheel boy and the roundabout, which was a wheel at each end of the walk where the spinners spun the thread back and forth. Was not found at the Diman’s Ropewalk, and the old spinners’ song:

“I’ve been to France, and I’ve been to Dover,

And now I’m on the roundabout along with Daddy Grover.”was never heard.

The writer has heard stories of another small ropewalk that used to be in the south part of the town. You will find old advertisements in the Plymouth Memorial where Mr. Coleman Chandler had fishing lines, cod lines, and such small work to sell. He probably at one time was engaged in ropemaking business somewhere up South Street, but the writer has not as yet been able to find any records. It was reported that Mr. Samuel Sampson, who for many years of his life had charge of the hackling and the spinning ground in the old Plymouth Ropewalk used to work there; in fact, at one time he ran it. Small ropewalks in the early days were very common. In fact, it needed nothing than the spinner’s wheel, a few good stake heeds, a solid fence and good weather to make a ropewalk of sufficient size to make codlines, mackerel lines and small stuff. It is probable that the South Street Ropewalk was something along this line.

Plymouth Cordage Notes Vol. 1, No. 7, Oct. 15, 1925

Some Old Plymouth Rope Walks

(Robbins' Ropewalk, the long line along Town Brook, 1858)

In our review of the old Ropewalks of Plymouth, Robbins' Ropewalk surely merits our attention. First, it was one of the first built in Plymouth and the only one that in size and importance approached the Plymouth Cordage Company during the first quarter of its industrial life. Less fortunate than the Plymouth Cordage Company, it lasted but a few years beyond that time.

Founded by Deacon Josiah Robbins and built along the lower reaches of Town Brook makes its location of historical interest. The waters of the Brook turned three wheels before they reached the harbor.

The records of the Town show that in 1821 Josiah Robbins was granted leave to dam the Town Brook and put in a mill gate at its mouth. Before this time the banks of the brook were sedge flats and the mouth of the brook a tidal basin. The mill gate shut out the waters of the harbor and developed the power for the Ropewalk.

In 1838, by purchase from the different claimants, Josiah Robbins acquired all rights in the Grist Mill and water privilege at the point in Town Brook at what is now Spring Street and thus the power to drive the wheels of the Jenny House was secured, Mr. Robbins later transferring this property to the Robbins Cordage Company.

This Ropewalk was unique in structure. Built for its whole length over the brook, the headhouse of the Ropewalk was on Water Street, west side, just north of the bridge. The walk ran up to and under the arch at the foot of Spring Hill. At the arch, the building began to gradually incline upward at an angle that would carry the building over the dam at the site now occupied by the Grain Mill of I. Morton & Company, one of the water privileges early developed by the first comers, and which furnished power, in the memory of the writer, for Grain Mill, Hammer Shop, Wheelwright Shop, and at the time that the Ropewalk was in operation, for a shop occupied by Mr. Ellis Barnes, later of the firm of E. & J. C Barnes. In this shop the bobbins were made for the Ropewalk.

After reaching the level of the stream above the dam, the two-storied portion of the walk began, running to the factory or Jenny House, now occupied by the business of Wm. S. Kyle.

The conditions at the time this Ropewalk was built were favorable.It had a greater and better water privilege that that furnished by Nathan’s Brook where the prosperity of the Plymouth Cordage Company had its beginning, and the power of the brook, as has been before stated, could be utilized three times. Mr. Robbins was a public spirited man of good business ability and of that kindly nature that makes for good citizenship through love for his fellow man.

From the standpoint of transportation of that time, the Ropewalk was well situated. There was ample water at the wharf across the road for brigs, schooners, and sloop-rigged packets of that day, and a vessel could haul over to the dock for her cordage and a fisherman could take her cable aboard and coil it down. It was not even necessary to reel it into a coil. It could be carried from the ground on the shoulders of the ropemakers and the vessel’s crew.

The Robbins Cordage Company did have a period of successful business. Mr. Samuel Robbins was a good ropemaker, although it has been said by men who learned their trade under him that “He would cover the head of a bobbin with figures to see how many yarns to put into a stay.”

Statistics of the manufacture of cordage in Massachusetts for the year 1842 show nineteen ropewalks; we assume by the tonnage produced, using other than hand power. We find that the Robbins Cordage Company had a capital of $60,000. Tons of tarred cordage manufactured, 370; untarred, 150; total, 520 tons. Barrels of tar used, 925; men employed, 75.

The burning of the Jenny House in 1847 was a severe loss to the Robbins Cordage Company and this, with the legal complications in the rebuilding, was the beginning of the end.

The water privilege used to develop power for the Jenny House was the second in Plymouth Colony, the first being at Bill Holmes’ Dam, so-called by boys of half a century ago. Situated near the entrance of Morton Park, in 1633, by the order of the Court of the Colony, one Stephen Dean, one of the company who came in the Fortune in 1621, “Have a water wheel set up at the charge of the Colony”, the power from this wheel to be used for the grinding or beating of corn. The mill was run continuously until 1838 when the claims of the different owners were finally acquired by Josiah Robbins who sold it to the Robbins Cordage Co., which thus came into the possession of the mill and privilege.In 1847 the mill burned together with the Jenny House, and when the Robbins Cordage Company rebuilt, the jenny House was enlarged to cover both sites. Action was taken by the Town, for by a grant given in 1633, the condition required the continuance of the Grist Mill forever. At a meeting of the Town a vote was passed referring to the matter to the Selectmen for a full investigation as to the right of the Town. At an adjourned meeting, the Selectmen made a lengthy report. Based on the opinion of eminent counsel, adverse to the Town up to that time, for two hundred thirteen years a grist mill had stood on that spot, had ground the corn for the inhabitants of Colony and Town.

Just when manufacturing was discontinued we do not know. In 1858 the Jenny House passed into the hands of Nehemiah Boynton of Boston, who later sold it to Samuel Loring and for years it was used as a tack and rivet factory. A portion of the old Ropewalk was utilized as a carpenter shop and for scaling of wire and general storage. The remainder of the two-story portion as far as the arch bridge was taken down by Mr. William Weston and Mr. Henry Weston, Plymouth carpenters, and set up again in Roxbury, Mass., a suburb of the City of Boston, where it became a part of the Sewell and Day Cordage Company. The East Headhouse and a long section over the brook became the property of E. & J. C. Barnes and was used for storage of lumber and cooper shops where was made mackerel barrels and cranberry barrels. Later, sections were moved and used for different purposes; on portion near the present Brewster Gardens and used for a storehouse for tools, was burned in the fall of 1924. All that is left today of what was once the Robbin’s Cordage Company is in the factory on Spring Street, now occupied by the Bradford Kyle Co.

Many of the old ropemakers of the Plymouth Cordage Company began their ropemaking experience in the /

Continued on Page 2, Col 1Robbins Cordage Company. Mr. Eben S. Griffin, who for many years was foreman of the big or west ground, was one of the graduates of the Robbins’ Ropewalk. He often told of heaving wheel when the moonlight was the only light furnished the spinners and of walking into darkness under the arch to emerge into light on the other side.

Much of the equipment used by the Robbins Company was purchased by the Plymouth Cordage Company, and forty-five years ago, bobbins would oftimes be recognized. They were more difficult to put into the tarred frame, and were found most frequently on mornings when the glass was below 10 degrees, a banyan day.

In 1842 there were nineteen ropewalks in Massachusetts. Thirty-five years ago there were six large manufacturers of cordage within a radius of twenty miles of the State House. Today there are but two manufacturers of hard fiber cordage in our State.

The other plants abandoned, the business of the Plymouth Cordage Company has increased. The great number of spindles at Plymouth make it necessary fro us to go out beyond the boundaries of state and nation for a market and makes it imperative that, as a corporation and as individual workers, we maintain a standard that the world knows and trusts.

Loper. A swivel upon which yarns are hooked at one end while being twisted into cordage.