F. Jane Baker, 1986 (Part Two)

THE GENERAL STORE: 19th Century.

Harvey Bartlett married Nancy Holmes in 1828. They began their married life in the old 17th century house built by Giles Rickard on the west side of Sandwich Street. My aunt Mary Cooper, their granddaughter, told me a little about the house although she had never seen it. It was a typical for this area, one and one half story with a gambrel roof and a great central chimney. People traveled on foot in those days heading towards Boston or the Cape, settlers, strangers and Indians. Harvey never refused anyone shelter for the night. In cold weather, they would sleep in front of the wide kitchen hearth.

There were children born to the Bartletts. The little house was crowded and one summer the family lived in the barn, tore down the old house and built a more spacious home. In 1837, Harvey bought the lot south of his from Jabez Churchill, Jr., and built a general store. It is possible he used Churchill's old shop for a time before he replaced it with his new one.

I have Harvey Bartlett's ledger for 1844 - 45 with a list of 68 customers on the front page. Here are names of some of the families of the neighborhood taken from a ledger book of Harvey Bartlett's General Store for 1844 - 45: Bartlett, Holmes, Churchill, Whiting, Wadsworth, Sears, Burgess, Paty, Morton, Cornish, Cole, Lewis, Cobb, Robinson, Perkins, Leach, Blackmer, Allen, Manter, Harlow and Hoxie. The ledger shows us a different culture than our modern supermarkets. Simple raw materials bought in bulk made up the local diet and standard of living. Prices of April, 1845: eggs 6c a dozen, butter 20c a pound, coffee 19c a pound, tea 20c a pound, a quart of beans, 7c, saleratus 8c, sugar 10c a pound, molasses 33c a gallon, and five pounds of pork for 45c. Quantities unlisted were herrings @ 6c, or herrings 24c, clams 10c, coots 25c. One could buy 2 hats for 32c and two apples for a penny.

Dry goods included yarn, cambric, drilling, sheeting, calico (4 yards for 15c), cashmere and flannel. Suspenders were 10c, a pair of stockings 50c. One order rather more expensive listed: Mo. Shawl $5.00, spoons $5.50 and a wash stand $1.00. The store also acted as a bank where a customer could draw out money against his account if he needed cash. Son Harvey made and mended shoes. I think his shop was above the store. His accounts were listed in the ledger. Shoes cost 90c to $1.25, and for mending boots, the charge was 25c to 60c.

In the 1960's when visiting "Aunt" Amy Carnes Smith at Newfield House, I was told some of her memories of the Bartletts. Amy and her parents, Capt. William and Lucy Carnes lived next door to Harvey and Nancy, at 229 and 231 Sandwich St. As a small child Amy would "tag along" after Harvey when he went to the pasture for his cows, or when he was mending his fences. One day Amy fell and cut a gash in her head and Lucy, alone in the house with the child, cried out to Harvey to stop the bleeding. "He went up in the barn," said Aunt Amy,"and came back with some dirty, dusty old cobwebs and laid them over the cut and, do you know, it healed perfectly!

Harvey's grandchildren came from Boston to spend their summer vacations. They were Jennie, Mary, Guy, and Gertie Cooper. Said Gertie, the youngest, to Amy "Why do you always follow him around? He's MY grandfather!"

Amy and Harvey entered the Bartlett kitchen one day where his wife Nancy was busy with household tasks. Harvey went into the next room, and Nancy could hear him opening a drawer in the bureau. "Harvey, what are you after?" "I just thought I'd like to give Amy a nickel." Such generosity did not meet with Nancy's approval. She was manager of the household. One can sense it in her profile if you look closely at the silhouettes of this couple made at about the time of they were married.

She

was an expert needlewoman as exemplified by her beautiful sampler made

in 1823 when she was fifteen. Her instructor was probably Maria de Verdier

Turner, an accomplished European woman who became the wife of Captain

Lothrop Turner of Plymouth. (See Mary M. Davidson's book of Plymouth Colony

Samplers). There is a scene of Mount Vernon worked below the alphabet

and a handsome border of roses and other flowers. The verse is from Alexander

Pope: "T'is education forms the common mind. Just as the twig is

bent the tree's inclin'd."

She

was an expert needlewoman as exemplified by her beautiful sampler made

in 1823 when she was fifteen. Her instructor was probably Maria de Verdier

Turner, an accomplished European woman who became the wife of Captain

Lothrop Turner of Plymouth. (See Mary M. Davidson's book of Plymouth Colony

Samplers). There is a scene of Mount Vernon worked below the alphabet

and a handsome border of roses and other flowers. The verse is from Alexander

Pope: "T'is education forms the common mind. Just as the twig is

bent the tree's inclin'd."

Nancy's "twig" was bent to tell the truth. When her grand-daughter Mary invited a little girl in to play, Nancy greeted her with "Who be ye?" then she added "Dreadful homely child, an't ye?!" It was an embarrassment which Mary never forgot.

Mary

said that she always had to wear old clothes through the summer as grandmother

Nancy put away the best ones in "the front clothes press". This

was a small room over the front stairs that served as a general closet

for the household. Mary loved clothes but there was little occasion to

wear them other than at a church sociable. One summer evening Mary and

another girl in the neighborhood planned to attend one of these. The young

girl came running into the yard calling excitedly, "Mary, they're

going to serve a collation." At this point she stumbled and fell.

She picked herself up quickly and ran almost breathless up to Mary and

said, "They're going to serve a col- col- a collision!"

Mary

said that she always had to wear old clothes through the summer as grandmother

Nancy put away the best ones in "the front clothes press". This

was a small room over the front stairs that served as a general closet

for the household. Mary loved clothes but there was little occasion to

wear them other than at a church sociable. One summer evening Mary and

another girl in the neighborhood planned to attend one of these. The young

girl came running into the yard calling excitedly, "Mary, they're

going to serve a collation." At this point she stumbled and fell.

She picked herself up quickly and ran almost breathless up to Mary and

said, "They're going to serve a col- col- a collision!"

The daughter of Harvey and Nancy who inherited their house was Almira, who married George Cooper of Plymouth. Their early married life was spent in South Boston where George worked as a mason for his brother Isaac, who was a contractor. Among certain well known buildings they erected were Franklin Square House, The old Natural History Museum (Bonwit Teller's, 1980) on Berkeley St. and the New Old South Church in Copley Square. George learned to speak Gaelic from his Irish co-workers and both he and his son Guy (my father) never failed to celebrate St. Patrick's Day by singing songs and wearing "of the green". Perhaps George absorbed a bit of Irish fantasy for when he was working at the very top of the afore-mentioned church tower, he was visited by a butterfly that hovered near him for so long a time that he believed it to be his mother's spirit come to protect him in that precarious place.

Harvey Bartlett, Sr. died in 1885. His second son, Ansel, took over the general Store at Jabez Corner. Ansel had served as a mariner during the Civil War. He never married. Some of his books were in the Bartlett family house when my father inherited it in the 1920s, two of them being a large leather bound volume, the Complete Works of William Shakespeare illustrated with steel engravings and Ancient Landmarks of Plymouth by Wm. T. Davis.

In his ledger of 1898-99 I find very little change in the stock or prices of the store. The list of customers had changed. There were twice as many women as listed by Harvey. Her had two, Mary Bartlett and Mary Perkins. Ansel had four; Ester Bartlett (his sister-in-law), Mrs. Harrison, Mrs. Sarah Manter and Miss Maggie Morton.

Ansel sold imported fruit; oranges, lemons and bananas. One lobster, 25c; overalls, 50c; stockings 60c, up 10c from Harvey's day.

When someone in the neighborhood was stricken by unusual illness or other misfortune, Ansel would post a paper in his store with the name of the unfortunate person and the circumstances. Beneath this he would write his own name and the amount of money he was giving to the cause. Customers who came to the store were expected to do likewise. Ansel collected the funds and saw that they were used for the proper purpose. This was probably an ancient custom passed down through the generations.

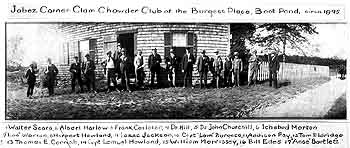

This was the era (1880s - 1890s) of the Jabez Corner Chowder Club. They met in rooms over the store for dinners and sociability and to play cards, checkers and cribbage.

Some

members of this Club were photographed in 1899 at the Burgess Place at

Boot Pond (now the house of Carroll Daley). Among them were Walter Sears,

Albert Harlow, Dr. Hill, Dr. Churchill, I. Morton, F. Churchill, H. Howland,

H. Morrissey, W. Edes and Ansel Bartlett. "Anse" is holding

up the cane or broomstick as though to lead a parade. This picture is

ours with the compliments of Nathaniel Morton so it is stated on the back.

It was taken with a wide angle lens.

Some

members of this Club were photographed in 1899 at the Burgess Place at

Boot Pond (now the house of Carroll Daley). Among them were Walter Sears,

Albert Harlow, Dr. Hill, Dr. Churchill, I. Morton, F. Churchill, H. Howland,

H. Morrissey, W. Edes and Ansel Bartlett. "Anse" is holding

up the cane or broomstick as though to lead a parade. This picture is

ours with the compliments of Nathaniel Morton so it is stated on the back.

It was taken with a wide angle lens.

At Jabez Corner, there was always a Clam Bake to which everyone in the neighborhood was invited. It was held in a field at the foot of Howes Lane which overlooked the harbor. Tables were set up under the "Balm of Gilead" trees. Besides the clams, lobsters and vegetables of the Bake, there were homemade pies, cakes and cookies and lemonade. At high tide, there was a sailboat race and there were probably games.

Croquet was very popular at this time. One warm summer afternoon Anse and his friends were playing this game on a strip of lawn just outside the store. A smart looking stranger drove up, hitched his horse to the post and entered the store. No one was there. The stranger came out intensely irritated and expressed himself in no uncertain manner but all eyes were centered on the game. As his voice and indignation rose the stranger was approached by "Sam B" Holmes purse in hand, saying quietly, "If any of these gentlemen owes you money, I will be glad to cash it."

Some who read this may be familiar with the picture of "Anse" Bartlett's store which appears in a booklet issued by the Plymouth Bank and the Plymouth National Bank on their 125th year. Ranged along the wide front step of the store are Captain Ben Sears, Captain Wellington Lamberton, Captain Lionel Churchill, (in the doorway) Guy Cooper (Ansel's nephew and later owner of the store), Lemuel Howland, Ansel Bartlett and Sam B. Holmes.

Lionel (pronounced li o' nel) had bought some lamb one morning for his wife to make a stew. "How was the stew?" someone asked him that afternoon. "We--ll," he spoke as always with a drawl," We--all - I'd as soon step outside and let the northwest wind blow through me." Lionel owned a ship, the Jennie Cushman. His daughter Mary, when she was a very old lady, gave the framed picture of the ship to my father. It is a drawing of the "Jennie Cushman Entering the straits of Gibraltar."

After Lionel retired from the sea he took various other short jobs. One day he was laying tarpaper over a new roof. The chimney of the house had not yet been built but a space had been cut for it in the roof. Lionel, busy with the hammering, didn't notice when his helper, Billy Sherman, suddenly disappeared. Onlookers saw and yelled "Lionel! Lionel! Billy's fallen through the chimney hole!" Lionel continued to hammer until the nail was properly positioned, the he turned toward his informers on the ground below, and drawled, "He always does that."

Billy's last mishap was fatal. He was in a dory with friends. It was getting dark and the winds and waves were rising. The friends sang cheerfully for they had all imbibed a fair amount of what my father called "Oh be joyful." Billy believed he had better get home. He mentioned something about walking on the water, recalling hearing that this had been done. With this prospect Billy left the boat.

Introduction

Part One: Wellingsley

Part Two: The General Store