PILGRIMS OF THE CARIBBEAN

Peggy M. Baker

A young singer, recently performing at one of Plymouth’s summertime waterfront festivals, began the set by telling of her recent tour of Europe. She thought it was a wonderful coincidence that she had just performed in Spain – the very place where Columbus had set sail in 1492 – and, now, here she was performing in Plymouth – the very place where Columbus had landed!

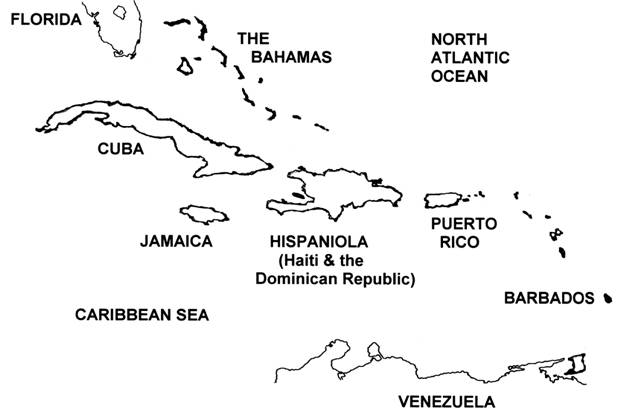

Columbus, of course, NEVER landed in Plymouth. He never even made it to mainland North America! He explored the Caribbean, claiming the islands of the West Indies for Spain, which established settlements on Hispaniola, Cuba, Jamaica and Puerto Rico. Soon, treasure fleets, carrying silver and gold from the New World, began to travel throughout these islands and, across the Atlantic, back to Spain.

Now, while Spain was colonizing (and profiting from) the Caribbean, what was England doing?

Not much! There were a few exploring ventures – but in the North Atlantic, not the Caribbean. England had neither the finances nor the political will to challenge Spain.

England’s Henry VII was looking for Spain’s approval. In an effort to validate his new Tudor dynasty, he married his eldest son Arthur to Katherine of Aragon, the daughter of Ferdinand & Isabella of Spain. The marriage ended (if it ever began) when Arthur died. Younger brother Henry became heir – and married his beautiful former sister-in-law, with the results that we all know from Masterpiece Theater if not from history books.

On Henry VIII’s death, his 9-year-old son Edward briefly reigned. England was distracted by internal political and religious controversies, and threatened by a French-Scottish alliance. The last thing England needed was conflict with Spain.

On Edward’s death at age 16, the throne went to his sister Mary. Mary was not only the daughter of Katherine of Spain (and, therefore, granddaughter of Ferdinand and Isabella), she also married the heir to the Spanish throne. There was no thought of challenging Spain while Mary was queen! The situation changed when Mary’s half-sister, the Protestant Elizabeth, came to the throne.

A shrewd politician who raised procrastination to an art form, Elizabeth tried to keep relations with Spain neutral. But the tremendous wealth pouring into Spain from the New World caused deep anxiety and deep jealousy.

In 1580, the English government declared that it would no longer recognize Spain’s claim to own the Caribbean islands. After that, hundreds of English ships cruised the Caribbean plundering Spanish settlements and capturing Spanish ships loaded with gold and silver. Some privateers, like Sir Francis Drake, raided on behalf of the Queen. Others were financed by London merchants (who put more money into piracy in the Caribbean between 1560 and 1630 than into any other overseas commercial venture). These English privateers plundered Spanish settlements and captured Spanish ships loaded with gold and silver.

Hostilities between England and Spain continued to mount. While the English depredations against the Spanish treasure fleets were not officially acts of war (the Caribbean was considered “beyond the line,” outside the territorial limits of European treaties), they certainly were a source of continuing and severe irritation. When the Spanish reprisal came, however, it was aimed at the very heart and soul of their enemy, with an attempted invasion of England itself. The great Spanish Armada sailed (and was defeated) in 1588.

The first actual English settlements in the West Indies did not begin until the NEXT monarch, James I. And the settlements happened in stages, starting with an island that is close - but not quite the Caribbean.

In 1609, a fleet bound for Virginia was caught in a storm. One ship went aground on Bermuda, an island discovered by the Spanish in 1503 but left unsettled. The 150 passengers on board all survived. One of them, Stephen Hopkins, went on to foment a mutiny on the grounds that the authority of the governor ceased when the ship was wrecked. This was probably the same Stephen who sailed on the Mayflower. The survivors lived off the land for 10 months before building several small boats and sailing to Jamestown.

The incident brought Bermuda to the attention of the Virginia Company and, probably, to the attention of William Shakespeare. The incident seems to have been the inspiration for Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest, written in 1611. Bermuda received an independent charter in 1615; one of the largest investors was the Earl of Warwick, a signer of Plymouth Colony’s Peirce Patent. Bermuda became a strategic post in the struggle with Spain.

Everything went along smoothly in Bermuda for several decades. Bermuda was established as a self-governing colony with the right of popular election and, in 1620, the first meeting of the Bermuda Parliament was held. In the 1640s, however, a serpent reared its head in Paradise. Given the priorities of the 17th century, it is no surprise to learn that the serpent was – RELIGION.

Several Bermuda ministers renounced the Church of England and formed an Independent church like those in New England. This caused considerable dissension in the community, dissension that was exacerbated by the stress of the English Civil War. (The Civil War, 1642-1653, was waged between the ultimately unsuccessful Royalist forces of Charles I and the more “Puritan” Parliamentarian forces of Oliver Cromwell.)

The Independents decided to leave Bermuda and establish their own settlement, 800 miles southwest of Bermuda on one of the islands of the Bahamas. The Bahamas had been known since Columbus’ time, but were thought of, in the words of the English geographer William Castell, as “so many, and of so little worth.”

Permission to create such a settlement had to be obtained from the English Parliament.

In 1646, Captain William Sayle set out from Bermuda for London. And he went – by way of Boston! That November, he attended a Thursday lecture given in Boston by the Reverend John Cotton, a fact noted by (Pilgrim) Edward Winslow. Sayle then sailed for London, where he received permission to establish the “Company of Adventurers for the Plantation of the Islands of Eleutheria.” Eleuthera is the Greek word for freedom; “freedom” meaning, in this context, freedom to worship in the approved Independent mode.

Sayle returned to Bermuda in October 1647 and, sometime in 1648, he and 70 prospective settlers headed south to the Bahamas. Among those 70, was a Mayflower passenger by the name of William Latham.

In 1620, Will Latham had been a young boy in the company of John Carver. He appeared infrequently in the records, he never married, and, according to Bradford’s Mayflower list, “after more than 20 years’ stay in the country, [he] went into England and from thence to the Bahamas Islands in the West Indies….”

Sometime soon after 1645, Latham sailed to England – undoubtedly by way of Boston and probably with William Sayle. Did Latham seek Sayle out in Boston and join forces with him then and there? Or did he learn about the Bahamas venture while on board ship and only then decide to throw his lot in with the adventurers? We will probably never know.

Chances are, however that the way Will Latham got to the Bahamas was by returning with Sayle to Bermuda and then setting out with him from Bermuda for the Bahamas in 1648.

That 1648 voyage did not go smoothly.

The ship (although not its shallop) was wrecked on the shores of the island of the Bahamas that is, today, still called Eleuthera. According to John Winthrop, who was keeping an eagle eye on the proceedings

all their provisions and goods were lost, so as they were forced … to lie in the open air, and to feed upon such fruits and wild creatures as the island afforded.

Which aren’t many - Eleuthera is mostly barren rock. Soon the settlers began to suffer. This is probably when Will Latham died. Bradford says: “there [in the Bahamas] with some others, [he] was starved for want of food.”In this desperate situation, Sayle and 8 men set out north into the Atlantic in the shallop to seek help. After 9 days, they arrived in Virginia. Help was sent to Eleuthera and the settlers (although not Will Latham) were saved. Eleuthera became the “birthplace of the Bahamas.” Sayle himself returned to Bermuda in 1657, serving as governor from 1658 to 1662 before being appointed, in 1663, the first governor of South Carolina.

The Eleutherans were not the only ones to leave Bermuda. Other malcontents sailed for Barbados, where a permanent and stable English colony had been formed in 1627. Barbados was one of the most successful and populous of the English settlements; by 1629, when there were about 300 English settlers living in Plymouth Colony, there were 1,800 in Barbados. Savvy New Englanders, such as Pilgrim Isaac Allerton, quickly established trade with the island, which became fabulously wealthy when the planters shifted from tobacco to sugar. By the middle of the 17th century, half of the English population of the Caribbean (60,000 in all) lived on Barbados and many were Royalists.

In 1650 (by which time, in England, Oliver Cromwell was firmly in control and King Charles I had already been executed by order of Parliament), the Governor of Barbados proclaimed for the Royalist cause and drove the supporters of Cromwell’s Commonwealth into exile. An English (Commonwealth) fleet was sent to deal with the rebellion. The Royalists quickly surrendered, but there was concern that, upon the fleet’s departure, they might regain power. The Commonwealth supporters on Barbados petitioned Parliament to put the island under the control of an experienced administrator of “approved fidelity to this Commonwealth” who possessed these qualifications:

1. A man truly fearing God and of good report among all men.

2. A man endowed with large abilities to perform such an undertaking.

3. A man well experience in plantations.The man recommended? Pilgrim Edward Winslow!

As lovely as it is to imagine “our Edward” with a suntan, perhaps wearing a gold earring and a beaded braid and holding, instead of a letter, a pina colada in a coconut… Edward Winslow was NOT chosen as governor. Instead, the nod went to Daniel Searle, a wealthy Barbadian planter.

Five years later, however, Winslow DID make it to Barbados, thanks to Oliver Cromwell.

Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell was planning a secret attack on the Spanish territories in the West Indies. The plan was called the “Western Design.” The idea was to seize Spanish strongholds and threaten the treasure routes.

Oliver Cromwell relied for his information on a group of men who had begun their careers as privateers operating out of New Providence Island, off the coast of Nicaragua.

New Providence was a most peculiar operation. It was colonized in 1630 by English Puritans who had envisioned establishing a “godly” community - but their major activity was privateering, or licensed piracy. They were heavily backed by the Earl of Warwick, also a backer of Plymouth Colony and there were connections with Boston, as well. A Thomas Cromwell – no relation to Oliver Cromwell – had shown up in Boston in 1636. A sailor, he entered the service of a Captain William Jackson who then left Boston and headed to New Providence.

Piracy does not lend itself to the creation of an orderly society of law-abiding men. It was no real surprise when, in 1641, the settlement on New Providence was wiped out by the Spanish. The English dream of successful privateering in the Caribbean lived on in the “Western Design,” however, and these English privateers lived on as well – and even came to Plymouth.

In May of 1646, Thomas Cromwell – by now a captain – sailed into Plymouth harbor with two prize ships. He was heading to Boston but ran into a gale.

According to Bradford

“He had aboard his vessels about 80 lusty men, but very unruly, who after they came ashore, did so distemper themselves with drink as they became like madmen, and though some of them were punished and imprisoned, yet could they hardly be restrained. Yet in the end they became more moderate and orderly. They continued here about a month or six weeks, and then went to the Massachusetts, in which time they spent and scattered a great deal of money among the people, and yet more sin I fear than money, notwithstanding all the care and watchfulness that was used towards them to prevent what might be.”So, with the information gleaned from these first English privateers, Oliver Cromwell set about organizing his Western Design.

The command was divided into military and civilian. The military command was divided between General Robert Venables and Admiral William Penn (father of the Pennsylvania Penn). The three civilian commissioners included Daniel Searle (the lucky man appointed governor of Barbados) and Pilgrim Edward Winslow.

The force of 38 ships and 3000 men (including our Edward) sailed from England on Christmas 1654 and arrived in Barbados a month later. Landing in Barbados, Edward Winslow met an old neighbor and sparring partner – William Vassall of Scituate.

Vassall, a wealthy and educated man, had settled in Scituate in 1635. His daughter Judith married Resolved White, Edward Winslow’s stepson, in 1640. In 1643, the Vassalls moved to Marshfield, where William became a town officer and would have come into close contact with Edward Winslow, who also lived in Marshfield.

Vassall was an outspoken advocate of religious freedom who proposed that all members of the Church of England be admitted to communion in the New England church. In 1646, he took a petition to England claiming that he and his fellow dissenters, as freeborn subjects, were being denied their liberty. Vassall sailed on the same vessel as William Sayle and Will Latham.Edward Winslow and William Bradford were adamantly opposed to Vassall’s proposed freedom of religion policy and, thanks to Winslow’s efforts to counteract Vassall, the petition was unsuccessful. Vassall then left England and settled in Barbados, a colony with a very mixed population – Church of England, Puritans, Roman Catholics, even a congregation of Sephardic Jews with their own synagogue - that offered relative freedom of conscience to all persons. Vassall prospered, becoming one of the richest and most influential planters on Barbados.

Once on Barbados, Penn and Venables were able to recruit an additional 600 troops, untrained and badly disciplined, from among the colonists. Supplies ran low, Venables and Penn began squabbling, morale sank.

Venables and Penn finally agreed to attack the main city on the Spanish-held island of Hispaniola. The first attempt was a futile exercise in mismanagement. The English never even got near the Spanish. The second attack was routed. Edward Winslow urged a third attempt but the troops refused to attack again. The attempt on Hispaniola was abandoned.

A council was held to decide what to do next. Return to England in defeat? Or find an easier Spanish island to attack (even if just to raise morale)?

The decision was to attack the small and almost-undefended Spanish settlement on Jamaica. All the expedition leaders agreed – except one. Edward Winslow did not believe that the troops would so easily forget their defeat at Hispaniola. Winslow, however, was overruled and the fleet sailed for Jamaica on May 4, 1655.

The next day Edward Winslow’s health began to fail. According to his manservant, the disgrace of the English army on Hispaniola had broken his heart.

On May 8, 1655, Edward Winslow died. The next day, he was buried at sea where

our ship gave him 20 guns, and our Vice-Admiral gave him 12, and our Rear Admiral 10, and so we bid him adieu, having a fresh gale of wind…The fresh wind took the English fleet to Jamaica, where 7000 English forces confronted 200 Spanish soldiers. Venables and Penn offered the vastly outnumbered Spanish an entire week to surrender. The Spanish took the opportunity to escape either to Cuba or the mountains, taking all their valuables with them.

The only result of the enormously expensive Western Design? One thinly-populated island and no plunder.

Penn and Venables knew that Oliver Cromwell would not be happy. Leaving most of their troops behind, they scooted back to England in a desperate futile attempt to save face and explain away their failure. Both officers were charged with deserting their posts and, after a brief imprisonment in the Tower, were relieved of their commands.

Thanks to the men they left behind, Jamaica became a notorious center for buccaneering as bands of English pirates roved and plundered and terrorized Spanish communities. One of these pirates, originally brought to the West Indies by Penn and Venables (and Winslow!) and then left behind, became so wealthy and famous that he was eventually knighted by King Charles II. Sir Henry Morgan then retired from privateering for a safer occupation, the production of rum. Today, the rum named after him - Captain Morgan Rum - is the fourth largest brand of spirits in the United States and the eleventh largest in the world.

So - Ahoy, maties! And – Yo! Ho! Ho! Next time you raise a glass - even if it’s not filled with rum – give a toast to the memory of Pilgrim Edward Winslow, the Western Design and the Pilgrims of the Caribbean!

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Bangs, Jeremy Dupertuis. Pilgrim Edward Winslow: New England’s first international diplomat. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2004.

Bridenbaugh, Carl & Roberta. No peace beyond the line: the English in the Caribbean, 1624-1690. New York: Oxford University Press, 1972.

Calder, Angus. Revolutionary empire: the rise of the English-speaking empires from the fifteenth century to the 1780s. London: Jonathan Cape, 1981.

Dunn, Richard S. Sugar and slaves: the rise of the planter class in the English West Indies. Williamsburg, Va.: Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1972.

Hassam, John T. “The Bahama Islands: notes on an early attempt at colonization.” In the Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Second Series. Vol. XIII. Boston: The Society, 1890. Pages 4-58.

Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. Providence Island, 1630-1641: The other Puritan colony. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Miller, Hubert W. "The Colonization of the Bahamas, 1647-1670," The William and Mary Quarterly Vol. 2 no.1 (Jan 1945): 33-46.

Rabb. Theodore K. Enterprise & empire: merchant and gentry investment in the expansion of England, 1575-1630, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967

Taylor, S.A.G. The Western Design: an account of Cromwell’s expedition to the Caribbean. Kingston, Jamaica: Institute of Jamaica, 1965.

Williams, Neville. The sea dogs: privateers, plunder & piracy in the Elizabethan age. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1975.