Thanksgiving

The Biography of an American Holiday

James W. Baker

University of New Hampshire Press, 2009

Chapter 5 Nineteenth-Century Holiday Imagery in Literature and Art

The national adoption of Thanksgiving would not have occurred without the efforts of expatriate New England advocates such as Godey’s editor Mrs. Sarah Josepha Hale and all the anonymous Yankees who worked to introduce the holiday in their respective towns and states. Their efforts to “sell the holiday” to the American people were greatly enhanced by the explosion in popular periodicals after 1830. Earlier, the public’s impression of Thanksgiving—what it signified and what was appropriate to its celebration—derived largely from personal experience, hearsay, or a few references in texts or newspapers. The “serious” Thanksgiving publication was still the sermon, and its prominence continued unabated through the Civil War. In the 1830s and 1840s, however, a technological revolution in the publishing industry took place, powered by the rapid improvement in printing technology through steam presses, pulp paper, cloth binding, steel engraving, and cheap lithography. Spurred by cheap printing, writing became a profitable enterprise, whereas once only the independently wealthy or artistically determined could afford to toy with authorship. In very short order, the era of mass production opened up vast new markets, such as “domestic fiction,” for aspiring writers, many of them women: “The leading producers of domestic fiction (castigated as ‘a damned mob of scribbling women’ by an envious Hawthorne) were all making tidy profits. The Atlantic was paying poets fifty dollars a page, as opposed to the two dollars offered by the New England Magazine in 1835; compensation for literary journalism would triple between 1860 and 1880.”1 It was these “scribbling women” and their male counterparts who carried out the literary exposition of Thanksgiving, ensuring that even those unfortunates who had not grown up with the holiday in New England would understand the significance of the day and how it should be observed.

The social shift toward separate male and female domains (outside the home versus domestic), and the cultural shift toward the perspective of women and children (i.e., toward the domestic “feminine” sentiments described in the previous chapter), were reflected in popular literature of the time, which was dominated by women’s magazines and illustrated weeklies such as Frank Leslie's Illustrated or Harper’s Weekly. Godey’s Lady’s Book, followed by its imitators Graham’s and Peterson’s, far outdistanced all masculine rivals. When Godey’s was in decline in the 1860s, it could still claim 150,000 subscribers as opposed to Harper’s 110,000.”2 The feminine influence also produced a flood of best-selling “domestic novels” depicting the tribulations of pure-hearted but oppressed women struggling to defend home life against the cold, external world. The moral fortification of the home—under the aegis of the enlightened homemaker—against the rough-and-ready masculine world of business and politics became a dominant middle-class fixation in the antebellum period. As Ann Douglas has demonstrated, the middle-class women involved in this “domestic revolution” found ready allies among the liberal clergymen of the era, who had been deprived of the political and social clout of their established Puritan predecessors. Laying claim to the social conscience of their generation, they instituted a regime of “sentimental” values in place of the old Enlightenment rationality and the tough-minded, aggressive Calvinist theology of the previous era. Obliged to rely on diffused “influence” in place of political or economic power, this intelligent and dedicated alliance effectively manipulated the popular press to promulgate its agenda. Feeling and sensitivity were presented as morally superior replacements for worldly and economic seriousness.

As often where women were concerned, sentiment was wanted, not facts. Literally hundreds of nostalgic memoirs were penned in the Civil War period about vanished rural ways, old New England farmsteads, a once-abundant country Thanksgivings presided over by all-capable and generically hospitable housekeepers; such reminiscences, while valuable as a response to cultural change, hardly give a trustworthy account of it.3

It was through such efforts that women and clerical authors constructed the popular impression of the Victorian Thanksgiving holiday, with all its sentimental associations with domestic virtue.

The shift to sentimental values from “rational” or scientific ones had a tremendous influence on how Americans viewed and valued holidays. Holidays in general lost much of their earlier theological and political emphasis and were reworked under the influence of Victorian culture, in which emotionality was encouraged and individual sensibilities were played on to heighten domestic, patriotic, and pleasurably pathetic responses to the symbolic significance of each particular occasion. Evocation of emotional states and the manipulation of feelings by sentimental literature transformed Thanksgiving from a sober religious occasion followed by a decorous family dinner into an indulgent domestic-centered spectacle imbued with nostalgia, social sympathies, and narratives of melodramatic family predicaments. This emotive turn was enthusiastically endorsed by most Americans and indeed flourishes even today among the less sophisticated—despite the reaction against Victorian sentiment by intellectuals in the twentieth century—as can be seen in the mawkish holiday decorations and simplistic moral narratives that thrive in popular culture alongside the “social realism,” political concerns, and postmodern ironic detachment favored by the elite.

Public discussion about the behavior and significance appropriate to the holiday was presented in the popular literature of the day. It was through the flood of ephemeral stories and now-forgotten nineteenth-century novels that the contemporary construction of Thanksgiving took place. Most of these were published first in the popular journals of the time, and in early children’s books. There were no exceptional texts comparable in influence to Washington Irving’s Christmas scenes at Bracebridge Hall (1822) or Clement Moore’s ’Twas the Night Before Christmas (1823), but the Thanksgiving theme did attract a few well-known authors. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s descriptions of the day in Oldtown Folks (1869) and Louisa May Alcott's “An Old Fashioned Thanksgiving” (1881) are still read today (and found on the Internet), although their survival is due more to the celebrity of the authors than to long-term literary excellence. The pieces that had any staying power were excerpted for inclusion in the collections for schoolroom use that became popular at the end of the century, but most disappeared unnoticed. Interestingly, very few treatments of the holiday appear in the works of the major New England “local color” authors, despite the centrality in their work of maudlin Yankee themes such as poverty, enervated bloodlines, old maids, and the tyranny of custom. Perhaps the Thanksgiving story was already considered too much a regional stereotype by the time these stories appeared at the end of the century.

The predominant literary treatment of Thanksgiving before the colonial and Pilgrim themes became fashionable involved the holiday dinner, acts of charity, the gathering of the family in the ancestral mansion, and the return of distant or missing family members to the security and order of the home. These tropes might be presented as exemplary depictions of the holiday and the ethics that made it possible, or as cautionary tales that warned against the social forces outside the home that threatened this domestic idyll. The traditional meal itself remained a constant, and accounts differed only in the degree of descriptive detail and whether it was the feast of a prosperous farmer or city merchant, or a more modest meal enjoyed by representatives of the virtuous poor. Far more important in Thanksgiving domestic fiction was the interplay of character and motives among the guests assembled around the table, not unlike similar themes played out today in films and television shows dealing with the holiday.

Fictional use of Thanksgiving could be nothing more than an incidental inclusion of the holiday in a story of contemporary (and especially New England) life. Or it could exploit the domestic symbolism of holiday themes such as the family homestead and reunion to frame conflicts between the familial ideal and the perceived dangers of worldly temptation. In George Hill’s Dovecote (1854), for example, the melodramatic story of little Milly, who found a safe haven on the old New England farm of Dovecote, is interrupted by an affectionate description of a classic Thanksgiving that has no relevance to the story other than to reinforce the sunny picture of agrarian life. A good example of the full development of domestic subject matter is the 1850 novelette by Cornelius Mathews, Chanticleer: A Thanksgiving Story of the Peabody Family. The plot of the story is that Elbridge, grandson of old Sylvester Peabody, has been missing for a year, under suspicion of having murdered a Rev. Barbery before he fled. As the story begins, Peabody’s other grandson Charley hears the rooster Chanticleer crow for the first time since Elbridge left, and predicts his return. Sam’s grandfather, old Sylvester, who has the role of the wise and charitable rural patriarch, had declared Elbridge dead to their affections. As the Thanksgiving guests arrive, we see how each of them, having left the sanctuary of the family farm, has been seduced by the ways of the world. The eldest, William, is a successful merchant and landowner who has become obsessed with property, symbolized by an obscurely worded ancient deed hidden in the family house that might or might not give title to some local estate. Oliver has become a prosperous farmer in Ohio and married Jane, a Quaker (who may be guilty of a sort of reverse pride in her simplicity). His only interest is in crops, prices, and agrarian improvements. A very wealthy married daughter, Mrs. Carrack, has condescended to come this year after having avoided her humble parents for five years. She arrives in a grand coach with her two footmen and her supercilious dandy son, Tiffany. The widowed mother of Elbridge and a son-in-law, Captain Charley Saltonstall, who has retained a rough simplicity of manner and generosity, are contrasted to the Peabody siblings.

Amid the usual subplots—involving, in this narrative, good-hearted black servant Mopsy and her pumpkin, young grandson Charley, and the humorous misadventures of the unfortunate Tiffany—the holiday proceeds in classic fashion through the Thanksgiving meeting and the dinner until two strangers appear. They of course turn out to be Rev. Barbery (who had dropped everything to join the gold rush) and Elbridge. The latter, realizing that he was under suspicion, had gone after the luckless Barbery and brought him back to prove his innocence. On his lonely travels he pointedly avoided his uncharitable siblings, passing by Oliver’s home in Ohio and avoiding Tiffany in New Orleans. Sylvester is reconciled to his errant son but requires that he immediately marry his abandoned sweetheart, Miriam. She of course agrees, and this happy resolution redeems the others (barring Tiffany). William burns his old deeds, and Mrs. Carrack and Jane take part in a wool-spinning contest to show that neither has lost that fundamental domestic faculty.

In Chanticleer we have a full panoply of contemporary Thanksgiving symbols: the ancestral farmstead with its generous patriarchal master, the menace of worldly success and luxury in contrast to the homey virtue of old-fashioned, the embarrassment of the overrefined dandy out of his urban element, reunion with the prodigal child, true love and constancy rewarded, the classic Thanksgiving wedding, and even the symbolic virtue of the spinning wheel.

Another Thanksgiving story in which the virtue of the family home is didactically contrasted with the evil of the world is “Thanksgiving: A Home Scene,” which appeared in the Ladies’ Repository in December 1874. The story opens in the happy farm household of Kate and Edward Roberts and their four young children as they await the return of their eldest son from college for Thanksgiving. The themes of simplicity, self-sufficiency, and contentment are stressed: “[they were] just about to seat themselves at the tea-table, which was covered with the many delicacies that farm could supply, — golden butter from their own dairy, honey from their well-kept hives, baked apples, delicate biscuits, and dainty cake: all home comforts, which Mrs. Roberts took pride in seeing on the table.”4 Many years before, Fanny, one of Mrs. Roberts’ friends, who thought that bringing together a wealthy socialite and a shy, awkward countryman would be amusing, had introduced the Robertses to each other. However, the two unexpectedly hit it off, and Kate, much to the consternation of her fashionable circle, married Edward and went to live an old-fashioned life on the farm. Looking forward to Thanksgiving, Kate tells her husband that the elegant Fanny, who had married a wellborn, stylish young man, has not prospered: “the once beautiful, light-hearted Fanny Ludlow is but a faded wreck of her former self,” with an improvident husband who frequents gambling halls while she tries to support them with paid needlework—that Victorian woman’s curse. The Robertses therefore send a large hamper of Thanksgiving food to Fanny and her family, graphically demonstrating the superiority of rural simplicity to urban luxury and dissipation.

Thanksgiving fiction almost always involved middle-class families of English descent, although virtuous representatives of other groups such as poor or “decayed” Yankee families, honest Irish workers, or black servants were occasionally introduced as exemplary foils to unprincipled villains or ruined relations. Most stories were set in the present, or a generation or two earlier, and concerned with the usual tribulations of sentimental fiction such as saintly sisters or orphan children who die young, poverty brought about by deserting husbands or intemperance, or star-crossed lovers and hard-hearted fathers. The classic New England Thanksgiving described in Oldtown Folks (1869) by Harriet Beecher Stowe is set just after the Revolution. Oldtown Folks uses the Thanksgiving theme to show the contentment of the Badger clan in their rural homestead, but also as an occasion that introduces the cosmopolitan villain, Ellery Davenport, to his future wife, the innocent orphan Tina. Similarly, in Mary J. Holmes’ “The Thanksgiving Party” (1865), Thanksgiving is the setting in which wealthy and snobbish Lucy Dayton’s pursuit of Hugh St. Leon is thwarted when he marries the penniless Ada Harcourt—who turns out to be the well-bred daughter of a wealthy man who was ruined several years earlier. Also, Lucy’s beloved delicate sister, Lizzie, dies—which sends Lizzie’s lover out to be a missionary and starts Lucy on the path to moral recovery.

There are other sentimental tales involving reunions and Thanksgiving Day marriages, tales of soldiers returning after rumors of death to the folks back home, of acts of seasonable charity rewarded and brittle selfishness defeated, of prodigals welcomed back to the genuine family life of the countryside or bemoaning their fate in urban poverty and degradation. The unexpected return of a soldier or western émigré who saves the farm for the old folks at home was a perennial favorite, as in the Harper’s Weekly story “Zenas Carey’s Reward” (1863). Old Zenas and Melinda Carey take in a homeless veteran on Thanksgiving, in memory of their son who died at Gettysburg, only to find that their guest is a missing heir of a local magnate. The guest then forgives their mortgage and becomes like another son to them. An alternative “return” in which no redemption takes place is in Hawthorne’s “John Inglefield’s Thanksgiving” (1840), which he published under the pseudonym “Rev. A. A. Royce.” Here the errant child is sixteen-year-old daughter Prudence, who briefly returns to her father’s fireside where her twin sister, her brother, and the former apprentice Robert sit following the day’s dinner. For a moment she becomes again a part of the family she left months before for some unnamed enormities, becoming an actress or something worse, but she does not repent, and flees the fireside unshriven.

It was now the hour for domestic worship. But while the family was making preparations for this duty, they suddenly perceived that Prudence had put on her cloak and hood, and was lifting the latch of the door.

“Prudence, Prudence! where are you going?” cried they all, with one voice.

As Prudence passed out of the door, she turned towards them, and flung back her hand with a gesture of farewell. But her face was so changed that they hardly recognized it. Sin and evil passions glowed through its comeliness, and wrought a horrible deformity; a smile gleamed in her eyes, as of triumphant mockery, at their surprise and grief.

“Daughter,” cried John Inglefield, between wrath and sorrow, “stay and be your father’s blessing, or take his curse with you!”

For an instant Prudence lingered and looked back into the fire-lighted room, while her countenance wore almost the expression as if she were struggling with a fiend, who had power to seize his victim even within the hallowed precincts of her father’s hearth. The fiend prevailed; and Prudence vanished into the outer darkness.5

Similar themes are worked with typical coincidental twists in the plot of J. G. Holland’s Yankee epic in free verse, Bittersweet (1858). Set in the requisite old red New England farmhouse on a stormy Thanksgiving Eve, the poem begins with the gathering of the clan: two sons with their wives and families who have little to do with the story, and the individuals who are central to the plot—old Israel, the patriarch, his daughters Ruth and Grace, Grace’s husband David, and their adopted sister Mary. They become involved in a discussion of theological problems of sin, temptation, and faith that were still of great interest to the New England reader (Bittersweet was a much-reprinted best seller in its day), prefiguring the troubles related in the rest of the book. The party then breaks up. David and Ruth go on a tour of the cellar stores of cider, apples, salt meat, and other staples, while Grace and Mary go off to talk. They exchange stories of the faithlessness and adultery that married life has dealt them. Grace begins by telling Mary that she discovered David had been unfaithful to her, and how she angrily responded to his transgression. Mary, however, tops this with the confession that not only did her lazy husband Edward cheat on her but when he sank into drink and debauchery, she began to sink with him until he went off with his frowsy mistress in a balloon on July 4. Once Mary had recovered from all this, she vengefully tried to seduce a married man who had hired her to make an embroidered purse for his wife. Fortunately he resisted and even helped her to repent, which was how she was able to return to the sanctity of her old home.

Later that evening, when the family has regathered, a boy’s telling of the Bluebeard tale moves Ruth to denounce the innate bloodthirsty nature of men and boys, while David makes the very sentimental observation that

The girl is nearest God, in fact;

The boy gives crime its due;

She blames the author of the act,

And pities too

The denouement occurs when a ragged stranger rescued from the storm turns out to be the wretched Edward, who asks Mary to forgive him. Mary, in so doing, reveals that the man whom she tried to seduce but who ended up helping her was none other than her sister’s husband, David. Grace realizes that the “affair” she had so bitterly resented was in fact David’s effort to redeem Mary, not actual adultery. All are reconciled, and Edward, having accomplished his purpose, appropriately dies.

Children played an important role in adult Thanksgiving fiction, both as characters and as narrators reflecting the voice of the author in recalling the wonderful holidays of yesteryear. Mrs. Stowe used the boy Horace to narrate Oldtown Folks, which was based in part on her husband Samuel’s memories of South Natick, Massachusetts, and her/Horace’s portrayal of Thanksgiving is very similar to recollected accounts of the old-time holiday in contemporary nonfiction. In Julia Mathews’ Uncle Joe’s Thanksgiving (1876), a group of children work together to raise funds to return a small cottage to its onetime owner, the superannuated Uncle Joe, and his granddaughter “Delight.” The story also involves a returned reprobate, who dies after reconciliation with his family, and a good-hearted Irish couple. The presentation of the deed to the house takes place following a Thanksgiving sleigh ride, and and this scene takes full advantage of the charitable associations with the day, while leaving the church service and dinner as understood.

The Thanksgiving theme was also a popular vehicle for the didactic purposes of children’s literature. A children’s story illustrating familiar ideals is Mary and Ellen; or, The Best Thanksgiving (1854), which contrasts the temperaments and holiday experiences of two classmates: selfish Mary, who plans to visit her grandparents along with prosperous relatives from Boston and California, and humble Ellen, who expects no celebration at home with her poor, sickly mother. As might be expected, Mary has the worst of the two Thanksgivings. Her uncooperativeness almost prevents her from going to her grandparents’ house. She then overeats, spending part of the day quite uncomfortably but still enjoying the stories and popcorn. Ellen’s holiday on the other hand is redeemed first by the effort of her mother’s genial black caretaker, Aunt Ceely, who arranges for a basket of food to be sent to the Fisher household, and then by Ellen’s missing seaman father, who turns up having made a fortune in the California goldfields.

The American Sunday School Union found Thanksgiving a suitable subject for their tiny tracts to catechize children, such as thoughtless young Annie in Thanksgiving-Day (ca. 1866), in the proper Christian attitude of thankfulness:

M[other]: What is the reason we keep thanksgiving-day?

A[nnie]: O, I suppose for a holiday, like Christmas, and new-year’s day, or like my birth-day. Is it not, mother?

M[other]: It is for a better purpose than this, Annie. . . .

A standard depiction of the classic holiday, with patriarchal widower, gathered grown children, and two vacant chairs (for departed mother and daughter) can be found in The Family Gathering; or, Thanksgiving-Day (n.d.). Another family inquisition from Dotty Dimple at Play (1868), in Sophie May’s popular children’s series, provides a glimpse of the popular appreciation of Thanksgiving:

After the silent blessing, Mr. Parlin turned to the youngest daughter, and said,

“Alice, do you know what Thanksgiving Day is for?”

“Yes, sir; for turkey.”

“Is that all?”

“No, sir; for plum pudding.”

“What do you think about it, Prudy?”

“I think the same as Dotty does, sir.” Replied Prudy, with a wistful glance at her father’s right hand, which held the carving knife.

“What do you say, Susy?”

“It comes in the almanac, just like Christmas, sir; and it’s something about the Pilgrim Fathers and the Mayflower.”

“No, Susy; it does not come in the almanac; the Governor appoints it. We have so many blessings that he sets apart one day in the year in which we are to think them over, and be thankful for them.”

“Yes, sir; yes, indeed,” said Susy. “I always knew that.”6

Many people did feel that Thanksgiving was primarily “for” turkey and plum pudding, or perhaps pumpkin pie and cranberry sauce, and that like the modern Christmas it was primarily a time of indulgence, not piety. Educated adults appreciated its religious nature, although the religious element was far weaker by the mid- to late nineteenth century than it had been. In all the children’s books examined here examined for this study, only the two Sunday School Union titles assume attendance at church on Thanksgiving Day. In the others, the only individual who is described as having attended church is Aunt Ceely in Mary and Ellen.

Few of these stories, whether written for children or adults, had accompanying illustrations. They relied almost completely on literary means to describe (and prescribe) the holiday’s characteristics, echoing perhaps New England’s aniconic culture of sermons, essays, and verse. However, texts were only one of the ways in which the Victorians constructed the meaning of their evolving Thanksgiving holiday. From the 1830s on, an ever-increasing torrent of mass-produced graphics brought about a revolution in popular perception. Inexpensive prints and woodcut illustrations had long been popular in chapbooks and on broadsides, providing a rough visual complement to the text or captioning. Such images may or may not be considered as “art,” but their central importance in this instance is as an alternative “language” that created and provided meaning sometimes quite independent of any verbal expression. As W.J.T. Mitchell observes,

[L]anguage and imagery are no longer what they promised to be for critics and philosophers of the Enlightenment—perfect, transparent media through which reality may be represented to the understanding. For modern criticism, language and imagery have become enigmas, problems to be explained, prison-houses which lock the understanding away from the world. The commonplace of modern studies of images, in fact, is that they must be understood as a kind of language; instead of providing a transparent window on the world, images are now regarded as the sort of sign that presents a deceptive appearance of naturalness and transparence concealing an opaque, distorting, arbitrary mechanism of representation, a process of ideological mystification.7

Popular mid-nineteenth-century illustrated serials such as Gleason’s (later Ballou’s) Pictorial, Harper’s Weekly (and Harper’s Monthly and Harper’s Bazar, to a lesser extent), Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, or, for the family market, Every Saturday, the Youth’s Companion, the Child at Home, and Hearth and Home published both Thanksgiving stories and impressive holiday-themed engravings each year, but seldom in conjunction. The stories were usually unrelated to the pictures, which had their own short textual explanations. The often elaborate engravings, however, are a valuable source in themselves as a medium through which to view the Victorian Thanksgiving. Until the technological revolution in print took place, there had been few visual representations of Thanksgiving. Popular perceptions of the holiday were shaped entirely through personal experience or by hearing and reading about it. Texts would continue to be the most important means by which the American Thanksgiving was defined and bounded, but images grew to become another essential method through which popular culture determined what Thanksgiving was all about.

The first pictorial representations of Thanksgiving, such as those by John W. Barber (1828) or Charles Goodrich (1836), depict simple families assembled around a Thanksgiving table (see figure 5). These quaint, rather primitive images would soon be superseded by much more dynamic and realistic representations.8 Popular prints proved to be an effective vehicle for increasing public appreciation of Thanksgiving and for communicating its association with the themes that remain recognizably “Thanksgiving” today, such as New England, turkey dinner, and family reunions. The most famous such image is Connecticut artist George H. Durrie’s painting Home for Thanksgiving, which was published by Currier and Ives in 1869. Durrie specialized in winter scenes in New England, and Home for Thanksgiving shows a young man who has arrived at a Yankee farmhouse with his wife and child in a sleigh being welcomed by the old father and mother (see figure 6). No other nineteenth-century picture achieved the dissemination of Durrie’s image in later years, but scenes of reunions in family homesteads and crowded dinner tables presided over by the aged head of the family were repeated again and again in the illustrated papers.

Most popular Thanksgiving illustrations in the 1850s were images of contemporary celebrations. Each November or early December, journals such as Gleason’s, Harper’s, and Frank Leslie’s offered seasonal cover and story illustrations of the Thanksgiving holiday. These include the return to the old homestead, preparations for the feast (including pictures of turkeys being hunted, bought, slaughtered, and served), family and friends assembled at the dinner table, and after-dinner entertainments. A typical example that appeared in Gleason’s Pictorial for December 6, 1851, has a festive Thanksgiving dinner attended by men, women, and children with their aged hosts; the grandfather cutting a turkey; and a servant bearing a huge plum pudding. For November 11, 1854, Gleason’s depicted a turkey hunt. Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion for November 28, 1857, features a selection of images, including a family at dinner and the same people playing fox and goose and blindman’s buff with some abandon after the meal (see figure 11). There is also a wintry “coasting” or sledding picture and a “husking party” in the issue. The Harper’s Weekly issue of December 5 for the same year has an analogous picture of a large New England family at table (with the youngest children at a separate table) and two servants, and a lively image of blindman’s buff played in the kitchen. The Harper’s Weekly Thanksgiving issue for the following year has the standard dinner and a Thanksgiving ball. An American turkey shoot was published in the London Illustrated News in 1859, while the New York Illustrated News offered yet another New England homestead dinner—with a strong emphasis on the cider barrel—in Thanksgiving Dinner—Ephraim’s Speech (November 26, 1859). Off to the right are two lovers hidden in an adjoining room (see figure 13).

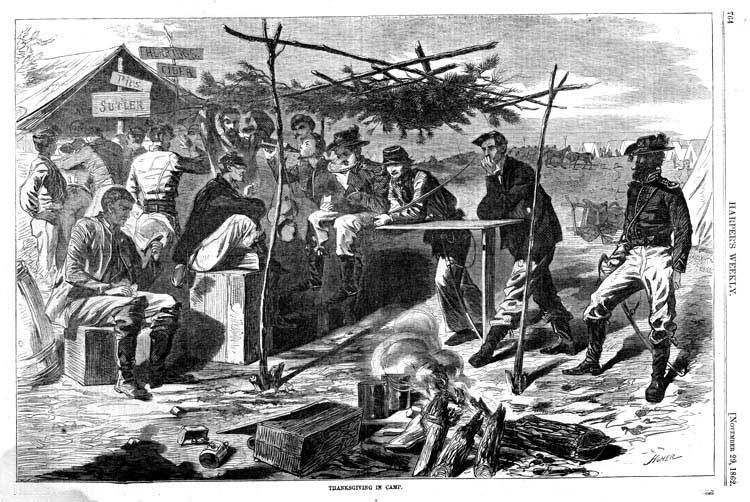

During the Civil War, Winslow Homer and other illustrators contributed scenes of Thanksgiving in the field where soldiers were doing their best to observe the holiday. In 1862, Homer published Thanksgiving in Camp in Harper’s Weekly, which depicts a sutler’s tent and brush arbor in which men are receiving pies and drink for the holiday (figure 17). In 1864, the organization of the Union Club collection of food for the troops at Delmonico’s and the Trinity Place depot was reported in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, while Thomas Nast chronicled the results of those same efforts among the soldiers and sailors. In Thanksgiving-day in the Army, Homer presents a sentimental print in Harper’s (December 3, 1864) in which two battle-hardened veterans are seen pulling a wishbone. When conditions allowed, the military encouraged Thanksgiving activities as a temporary anodyne to the rigors of the battlefield, as shown in Lossing’s Civil War in America (1866, vol. 1, p. 168). A full folio page by artist W. T. Crane is devoted to the “Thanksgiving festivities at Fort Pulaski, Georgia,” on November 27, 1862, including blindfolded wheelbarrow races, greased pigs and poles, a sack race, the dress parade, a Thanksgiving ball, and other activities.9 Illustrators also depicted Thanksgiving on the home front. The war’s close was duly celebrated in 1865 by Winslow Homer in a pair of prints in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated: Thanksgiving Day—the Church Porch, showing veterans, some with missing limbs, attending Thanksgiving Day services with their families (see figure 7), and Thanksgiving Day—Hanging Up the Musket, where the returning soldier hangs a musket marked “1861” beneath the remains of an old gun labeled “1776.”

After the war, Thanksgiving prints appeared regularly in Harper’s Weekly, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, and other periodicals. These images varied over a limited range, from Thomas Nast’s humorous cartoons of turkey-haunted nightmares suffered by overindulgent small boys to allegorical harvest compositions. Predictably, turkeys in the various stages of their role as principal entrée appeared regularly, as in the prewar Thanksgiving—Way and Means published in the November 27, 1858, issue of Harper’s Weekly, but pictures of New England farms and dinners declined in frequency as the other regions of the country developed their own traditions. Images of the classic New England family gathering so popular in the 1850s and 1860s were replaced by representations of colonial Thanksgivings. These as a rule retained the wintry character of the earlier contemporary Yankee images until the Pilgrims and their autumnal harvest festival shifted the seasonal focus to the milder days of early fall or November’s hazy, warm “Indian summer.”10 The decorations surrounding the text of President Andrew Johnson’s 1869 November proclamation in Harper’s Illustrated (November 30, 1869, p. 744) emphasize the peaceful harvest theme—including blacks picking cotton!—but include manufacturing and shipping as well.

When topics such as the return to the old homestead were revisited, they might be handled frivolously, as in the Frank Leslie’s Illustrated 1883 drawing Thanksgiving in New England—Returning Home from School, in which a fashionable urban matron and her three idle daughters (and their cats) await the coach bringing their son and brother from college, or in The Small-Breeds Thanksgiving—Return of the First-born from College (Harper’s, 1877), which depicts with the typical cynical condescension of the time an impoverished black family and the arrival of their son for the holiday dinner. As Franklin Hough observed in 1858, the Thanksgiving reunion was less often observed outside New England, and that theme may have seemed a bit threadbare to many Americans by this time.11 A new perennial favorite, the depiction of women in the kitchen preparing the feast, is represented by Etyinge’s Mixing the Thanksgiving Pudding (Harper’s Weekly, December 6, 1879).

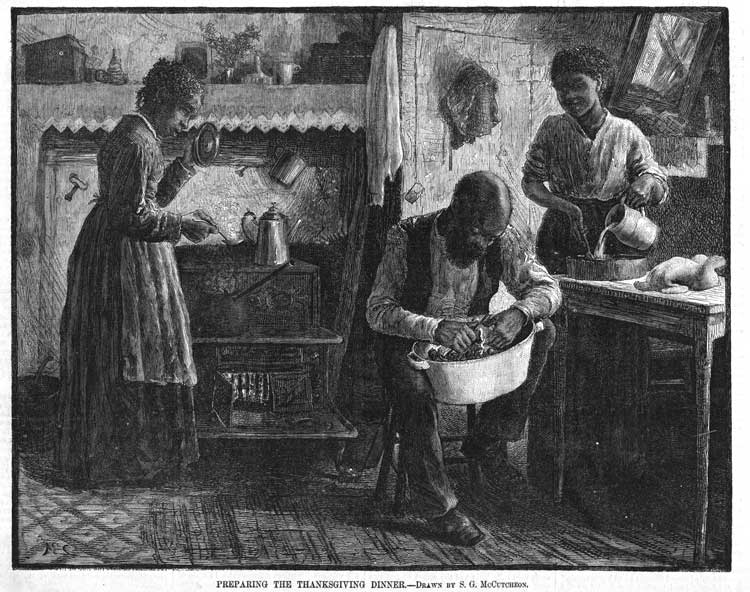

The use of blacks as representatives of Thanksgiving is interesting, as they are the only minority—except for Indians in historical images—to so appear on a regular basis. Except for Thomas Nast’s impressively “multicultural” prints (see below), Thanksgiving drawings and cartoons are almost entirely populated with old-generation Americans. Almost no Irish, Germans, Jews, or other ethnic groups regularly depicted in the popular press turn up in Thanksgiving pictures, yet blacks do so on a regular basis. Many of the images are of black cooks and servants whose role is to serve the holiday dinner, but the African Americans’ own Thanksgivings are common as well. Some examples are Thanksgiving Day—the Dinner (Harper’s Weekly, November 27, 1858); W.S.L. Jewett’s Thanksgiving—a Thanksgiving among Their Descendants” (Harper’s Weekly, November 30, 1867); E. A. Abbey’s Thanksgiving Turkey (Harper’s Weekly, December 9, 1879); J. W. Alexander’s Done Brown, Sho’s Yo’ Bo’n (Harper’s Weekly, November 26, 1881). There is a predictable seasonal variant on the stereotypical black chicken thief (an attribution shared by the white tramp), as can be seen in a cartoon in the Harper’s Weekly “Thanksgiving Number” for 1887. As Jan Pieterse notes, blacks were often caricatured as poseurs in the process of middle-class assimilation, and after 1890 also gradually assumed the burden of stereotypical poverty, replacing the dim-witted Irish, indolent Germans, and wily Jews.12 However, there are also dignified representations of black ministers, as in What the Colored Race Has to Be Thankful For” (Harper’s Weekly, November 27, 1886) or American Sketches: A Negro Congregation in Washington (Illustrated London News, November 18, 1876). Preparing the Thanksgiving Dinner by S. B. McCutcheon (Harper’s Weekly, December 4, 1880) depicts a black family getting ready for their dinner in the same respectable and sentimental fashion as is found in the many Yankee images over the years (figure 18). Even P. S. Newell’s After the Thanksgiving Service—Taking the New Minister Home to Dinner (Harper’s Weekly, November 27, 1897), while uncomfortably racist to modern eyes, exhibits what passed for well-intentioned humor in contemporary ethnic illustration. There appears to have been a strong impulse to associate blacks with the holiday in illustration, although I have been unable to find any text explaining why this was so. Perhaps it assumed a reciprocal sympathy with New England and the abolitionist tradition, or reflects some association with the alliances that marked the Reconstruction period. The African American Thanksgiving was so well established by the end of the century that it could be parodied in Judge in 1896 to show a table of Republican politicians in blackface, hosted by a black President McKinley, gathered to eat a scrawny turkey labeled “offices” (referring to partisan patronage). This connection persisted into the early twentieth century, especially on Thanksgiving postcards.

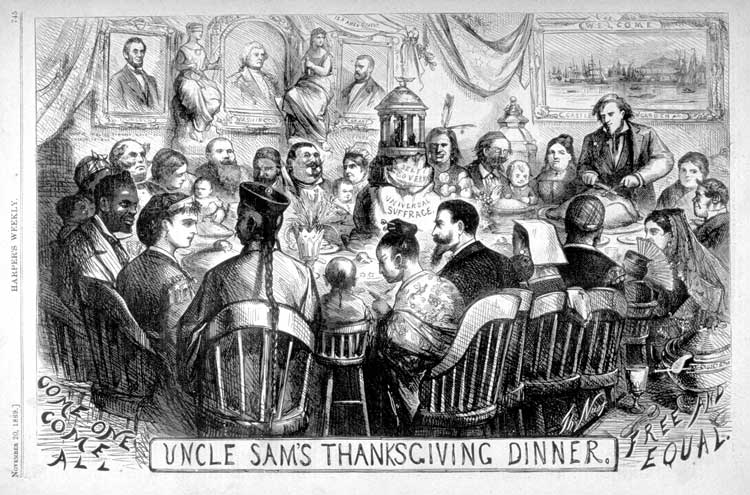

Thomas Nast, to whom we are indebted for so much of our national iconography including the Republican elephant, Democratic donkey, and jolly Santa Claus, deserves credit for attempting to recast Thanksgiving as America’s inclusionary holiday. As an immigrant himself, Nast apparently found in the Thanksgiving holiday a promise of national assimilation and/or ethnic equality. For example, in Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner, his November 20, 1869, drawing for Harper’s Weekly, Nast presents a dinner table presided over by Uncle Sam and Columbia around which are seated representatives of all the nationalities of the world waiting to break bread, or rather turkey, together (figure 19). On the wall behind are pictures of Washington, Lincoln, and Grant (the current president), and the lumpy centerpiece is labeled “Self Governance Universal Suffrage.” In The Annual Sacrifice That Gladdens Many Hearts (Harper’s Weekly, November 28, 1885), Nast offers a similar image, as representatives of various nationalities—American Indians, Africans, Irish, Germans, Scots, and others—line up for a piece of turkey carved on the “Union Altar” by Uncle Sam in colonial costume. Partisans of the Progressive movement would eagerly adopt this conceptualization of Thanksgiving as a celebration of national unity and toleration rather than nativist tradition in their efforts to stir the immigrant melting pot. Nast never developed an icon for the holiday as he did with Santa Claus for Christmas or the Republican elephant and Democratic donkey; there was not much that could be added to the reigning turkey in that line. By the time the Pilgrims arrived on the iconographic scene, he had left Harper’s and was no longer involved in crafting cultural caricatures.

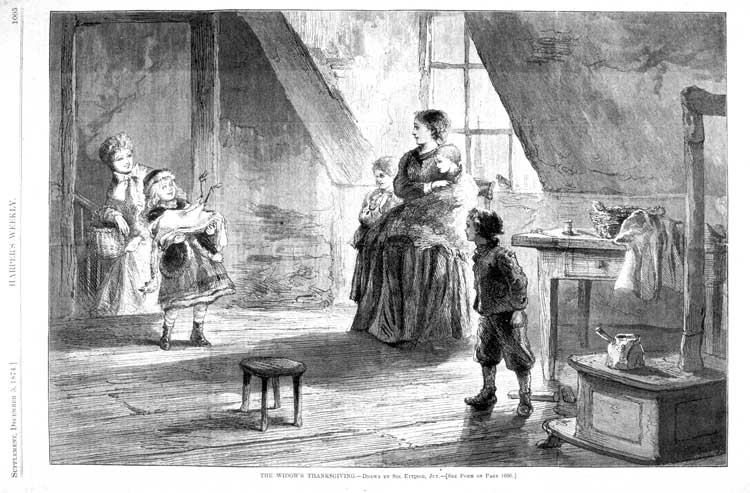

Traditional Thanksgiving charity was another popular topic for illustration. The charitable impulse might be presented in a sentimental manner as in the delivery of a basket of food to a widow and her children (figure 20) in a dreary city garret (Sol Etyinge’s Widow’s Thanksgiving in Harper’s Weekly, December 5, 1874) or in W.S.L. Jewett’s First Thanksgiving (Harper’s Weekly, November 28, 1868), where a small street-girl is given a meal of leftovers and, incidentally, a glimpse of bourgeois holiday spirit. Alternately, it might be presented by straightforward reporting, as in Thanksgiving Dinner at the Five Points’ Ladies Home Mission (Harper’s Weekly, December 23, 1865), or as a critical contrast between the excesses of the Gilded Age and grinding urban poverty. An evocation of the failure of the tradition of Thanksgiving charity in the anonymity of the city is provided by Winslow Homer in Thanksgiving Day—1860: The Two Great Classes (Harper’s Weekly, December 4, 1860), which contrasts the luxurious leisure of the wealthy with the desperate plight of the poor in scenes of someone stealing chickens or a lonely seamstress trying to earn a crust. The absence of charity is also evident in the humorous Frank Leslie’s Illustrated 1864 cartoon “So Near and Yet So Far.” Here a small boy is overcome just by imagining what the dinner might be like in a saloon to which enormous supplies of game and food are being delivered, reinforcing the certainty of deprivation amid holiday indulgence.

Thanksgiving illustrations sometimes showed people attempting to honor the holiday under conditions quite unlike the cozy scenes of domestic harmony. The loneliness of a failure’s shabby room (see figure 14) in A Thanksgiving Dream of Home (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, December 5, 1868) or the plight of men without family to turn to in Thanksgiving among the Homeless—in a City Restaurant (Harper’s Weekly, November 30, 1872) were especially poignant to period sensibilities. Similarly, the Wild West, like the battlefield, was a place where a little Thanksgiving spirit was a heartfelt need. Even during the rigors of the gold rush, treasure-seeking Yankees felt the need to recognize their traditional holiday, as shown in Thanksgiving in a Miner’s Cabin in Gleason’s (May 3, 1851). Pioneer life had its risks, as a pictorial sequence titled Thanksgiving in Michigan on the cover of Hearth and Home (November 30, 1871) makes clear: a family’s log house burns down, and they are forced to find refuge in a rough hut, but even if their Thanksgiving dinner is nothing more than bread and potatoes, they are still grateful for their lives and for supplies sent by the “Relief Association,” which will allow them to start anew. In Frederick Remington’s Thanksgiving Dinner for the Ranch (Harper’s, November 24, 1888) two rough cowboys are seen riding home with some rabbits and an antelope for the boys back at the ranch, while his White Man’s Big Sunday (Harper’s, November 26, 1896), perhaps a reference to the “First Thanksgiving,” shows a frontier housewife offering holiday food to several Indians who benefit from the charitable nature of the day.

The most significant new illustrative theme was the representation of Thanksgiving in colonial times. Historical paintings and drawings were exceedingly popular in late-Victorian America, even if such nineteenth-century historical art usually seems melodramatic and inauthentic to us today. It should be remembered that it was only recently that people had begun to be concerned with what the past actually looked like. For centuries, representations of the past had mirrored the fashions and styles of the time in which the illustrations were made rather than those of the period being depicted. The discovery of classical artifacts and the dissemination of their images in engravings had made it possible to approximate a generalized style of costume to represent biblical or ancient events even while the faces, landscapes, and furnishings depicted in the same images remained recognizably those of early modern Europe. As Roy Strong observes, it was the “wildly inaccurate” illustrated histories that appeared after 1770 that accustomed the public to the idea of “seeing” the past.13 It was not until the end of the eighteenth century that a conscious attempt to represent history accurately emerged, and it was at least another century before artists became familiar enough with historic costumes and artifacts to approach historical exactness.

The late-Victorian fascination with America’s colonial past was immeasurably advanced by the excitement surrounding the national Centennial and the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. Interest in the relics and customs of the colonial era had been increasing for some time, resulting in the restoration of Mount Vernon—America’s first “historic house”—and the “olde tyme” kitchens created and exhibited during the Civil War for the U.S. Sanitary Commission Fair (a forerunner of the Red Cross that assisted in the medical care of Union soldiers). There were at least six of these colonial kitchen fairs held in 1864 as charitable fund-raisers, in Brooklyn, New York City, Saint Louis, Indianapolis, and Philadelphia—all cities with New England societies. Although New York focused on the Dutch and Philadelphia on the German colonists, the other three were “New England Kitchens,” and it was the New England model that became the standard. Organized by local women, the kitchen exhibits were pioneering attempts to represent the spirit of the colonial past to the general public, which led to the institution of the historic house museum. Each exhibit was equipped with a large fireplace where antique cooking utensils were used to serve homey New England fare to visitors at long tables under festoons of dried apples. Costumed matrons operated spinning wheels and made quilts to demonstrate outmoded homemaking skills, surrounded by antiques such as “grandfather” clocks, candlesticks, teapots, Bibles, and pewter ware. All this domestic activity was fascinating to a generation that had grown up with iron stoves, chinaware, canned goods, and oil lamps. Like the classic Thanksgiving dinner, the New England Kitchen was a tangible evocation of the simple domestic virtues of the Revolutionary era.14

A direct descendant of the Sanitary Commission’s New England Kitchens was the New England Log-House and Kitchen exhibit at the Philadelphia Exposition in 1876. Like the earlier exhibits, the Log-House and Kitchen evoked the virtues of the Era of Homespun and the industry of the colonial housewife, even while it celebrated the very masculine War for Independence. Marling notes that “the relentless domesticity with which Washington and his era were presented at the Centennial Exposition suggests that conventional political and military history were matters of indifference to fairgoers and exhibitors alike.”15 The furnishings in the 1876 Log-House and Kitchen were not limited to Revolutionary-era antiques, however, but included a wooden cradle alleged to be Peregrine White’s and “John Alden’s” writing desk. A reproduction of “Elder Brewster’s tea service” (not that the elder ever served tea) was offered for sale. None of these were actual Mayflower relics, but like the spinning wheels and other objects they satisfied the avid curiosity about the antiques that animated the visiting public. Illustrations of the Sanitary Fair “kitchens” and the relics on display were widely distributed by Harper’s Weekly, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, and Centennial guidebooks, inspiring Americans to begin collecting indigenous antiques and making everyone familiar with a selective imagery of “old colonial days.”

The Log-House itself was perhaps the most blatant anachronism of them all. There had never been log cabins of this sort in colonial New England, but the log cabin’s symbolic role in contemporary American culture dictated the necessity of its representation. The pioneer/patriot/Pilgrim archetype celebrated at the exposition was therefore not only culturally compelling but also enthusiastically muddled. “Most of those who recorded in print their reactions to the Log-House displayed a remarkably elastic sense of history; the Revolutionary epoch stretched backward at will, for instance, to take in John Alden and Peregrine White and oozed forward again to accommodate a frontiersman’s log cabin of nineteenth-century design.”16 It is not surprising then that the attempt to represent Puritan Thanksgivings resulted in scenes full of inconsistencies apparent to the educated modern observer if not to her predecessors. The popularity of the colonial past and the Pilgrims led to a whole new way of looking at Thanksgiving history.

Like the sentimentality found in the literature of the time, this nostalgic evocation of the “good old days” in tangible form followed the contemporary preference for an emotional rather than a cognitive appreciation of the past, and paved the way for the eventual association of Thanksgiving with its ultimate historic association, the Plymouth “First Thanksgiving” of 1621. All these relics of the country’s preindustrial past would in time become icons and symbols endlessly reproduced in illustration and decoration to allow Americans to indulgently contemplate their emotive ties to Pilgrims and pioneers, and the ostensible significance of their autumnal holiday inheritance.

1 Lawrence Buell. New England Literary Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986, p. 57.

2 Ann Douglas. The Feminization of American Culture. New York: Anchor Press, 1988, p. 229.

3 Douglas, Feminization, p. 49.

4 Josie Keen. “Thanksgiving: A Home Scene”, The Ladies’ Repository, 2nd series, vol. 14, no, 6, Dec. 1874, pp. 426-430.

5 “John Inglefield’s Thanksgiving,”The United States Democratic Review. vol. 7, no. 27, March, 1840, pp. 209-213.

6 “Sophie May” (Rebecca S. Clarke). Dotty Dimple at Play. Boston: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co., 1910, p. 144-145.

7 W. J. T. Mitchell. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1986, p. 8.

8 John W. Barber, American Scenes: A Selection of the Most Interesting Incidents in American History. Springfield: D. E. Fisk, 1868, p. 106 (original edition, 1828); Charles Goodrich. The Universal Traveler. Hartford: Canfield and Robbins, 1837, opposite p. 36 (original edition. 1836).

9 Benson J. Lossing. Pictorial History of the Civil War in the United States of America. Philadelphia: George Childs, 1866, p. 168

10 An interesting parallel in late Victorian painting, where cloudy or overcast (wintry) scenes denoting seriousness and pre-industrial authenticity were superceded by sunny images of leisure and frivolity has been analyzed by Nina Lübbren, “North to South: Paradigm Shifts in European Art and Tourism”, Visual Culture and Tourism, David Crouch and Nina Lübbren, eds., Oxford: Berg, 2003, pp. 125-146.

11 Franklin B. Hough. Proclamations For Thanksgiving. Albany: Munsell & Rowland, 1858, p. xvi.

12 Jan Nederveen Pieterse. White on Black: Images of Africans and Blacks in Western Popular Culture. New Haven: Yale, 1992, p. 134, 170.

13 Roy Strong. Recreating the Past. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978, p. 20.

14 Rodris Roth. “The New England, or ‘Olde Tyme,’ Kitchen Exhibit at Nineteenth-Century Fairs”, in Alan Axelrod, ed. The Colonial Revival in America. New York: W. W. Norton, 1985, pp. 159-183.

15 Karal Ann Marling. George Washington Slept Here: Colonial Revivals and American Culture 1876 – 1986. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988, p. 34

16 Marling, George Washington, p. 40.