Thanksgiving

The Biography of an American Holiday

James W. Baker

University of New Hampshire Press, 2009

Introduction: A Thanksgiving Detective Story

These historical myths grow up silently. Some of them reign for centuries. Modern research has exposed many of ancient lineage and long acceptance, has torn away the mask and revealed them in their true character. Yet the historical myth rarely dies. No exposure seems able to kill it. Expelled from every book of authority, from every dictionary and encyclopedia, it will still live on among the great mass of humanity. The reason for this tenacity of life is not far to seek. The myth, or the tradition, as it is sometimes called, has necessarily a touch of the imagination, and imagination is almost always more fascinating than truth. The historical myth, indeed, would not exist at all if it did not profess to tell something which people for one reason or another, like to believe, and which appeals strongly to some emotion or passion, and so to human nature.

Henry Cabot Lodge “An American Myth”1

Thanksgiving Day! What a wealth of sentiment is evoked by this all-American holiday. The multitude of familiar images that spring to mind would require an American Dickens to do them justice: Intrepid, be-buckled Pilgrims and their dignified Indian neighbors sit down to dinner in the serenity of an eternally golden autumn afternoon. Radiant white-painted New England churches welcome cheerful congregations from local neighborhoods and the rural farmsteads that have supplied the bounty of the harvest. Shocks of corn and heaps of pumpkins dot the fields and fill the barns as the strutting monarch of the farmyard, the fattened Thanksgiving turkey, marches unaware of his imminent fate. Generations converge on old family homesteads where wrinkled grandparents welcome their returning members of the clan. High school and college football teams defend their honor just as preceding generations did, under crisp blue fall skies sensuously spiced with a faint aroma of burning leaves. Pies are drawn steaming from ovens in stoves on which bubbling pots foretell the coming feast. All of these traditional scenes are recognized by generations of Americans as embodying the essence of Thanksgiving.

But above all, there is the celebrated origin of the holiday in that fabled outdoor feast to which the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony welcomed their Native American neighbors back when it all began in 1621.

Despite disagreements over details, such as whether the Pilgrims or the Wampanoag Indians deserve the greater honor for the event, or if turkey was on the original bill of fare, the universal consensus is that the mythical Plymouth event was the historical birth of the American Thanksgiving holiday. The accepted narrative incorporating that event (i. e., the “Pilgrim Story,” of which Thanksgiving is the denouement) goes something like this:

In the autumn of 1620, a tiny, crowded ship called the Mayflower left Plymouth, England. On board were 102 passengers—a mixed company of pious Separatists and profane “Strangers” thrown together by fate (and their troublesome financial backers) on a perilous voyage to find new homes in the wilderness of British North America, or “Virginia”, as the entire territory was then known. The Separatists (sometimes identified as “The Pilgrims” proper, although this word is more commonly used to indicate the entire group of passengers) were English religious dissidents who had fled their homeland years before in the face of royal persecution to live in the safety of the tolerant Netherlands. However, poverty, the threatened loss of their English identity and the possible resumption of war between Holland and Spain induced them to emigrate once again, this time to England’s American territory. There they hoped to find a place where they could live unmolested and worship as they chose. The “Strangers,” on the other hand, simply sought a better life in a new world where land ownership and prosperity were more achievable than in tradition- and class-bound England.

After a dangerous, frightening and thoroughly uncomfortable 66-day voyage cooped up in the dark, dank, and smelly bowels of the Mayflower, they were immeasurably relieved to sight land on November 9. Following a fruitless attempt to continue on to their original destination at the mouth of the Hudson River, they decided to stay where they had ended up, in present-day New England. They anchored in Cape Cod harbor (now Provincetown harbor) on November 11, 1620. As they were now outside of the legal boundaries of their charter, some of the Strangers asserted that they were no longer obliged to live under the dominion of the “Saints” (as the Separatists commonly referred to themselves) but could strike out on their own. Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed, and the men of the party signed a momentous document called the Mayflower Compact that not only saved the colony by requiring all to live together under a government of their own making, but also introduced democratic principles of government to America, and in time inspired the United States Constitution.

Following a month of exploration on Cape Cod, which included a brief, bloodless foray with the Indian inhabitants themselves as well as the discovery of vacant Indian homes, providential corn supplies (which they took but later paid back with interest), and graves, an exploring party arrived at what is now Plymouth. It was a dark and stormy December night of wind and sleet as the little shallop (a coastal craft brought over in pieces on the Mayflower and reconstructed on Cape Cod) approached the entrance to Plymouth harbor. Although both sail and rudder were lost in the storm, the boat entered the harbor and safely anchored. Its passengers themselves on an island in the morning, and there they spent the weekend before crossing over to the mainland on Monday, December 11 (or December 21, by the New Style or Gregorian calendar), when they made the climactic landing on Plymouth Rock. The Mayflower crossed Massachusetts Bay a week later, and on Christmas Day (which the Separatists did not believe in), work began on the new village.

There followed the terrible “First Winter” during which all but a few persons suffered from exposure and disease, and half the Mayflower’s passengers and crew died. Nevertheless they persevered, and when spring came, planted their first crops and built homes and storehouses. On March 16, a lone Indian entered the settlement and astonished the colonists by greeting them in English. This was Samoset, a Native Sagamore from Maine, who had learned the language from English fishermen who made annual voyages to the Maine coast each year. On March 22, he introduced them to another Native man, Squanto, who had once lived at Patuxet, the site of the new Plymouth settlement, before being kidnapped by an English sea captain and sold into slavery in Spain. Remarkably, Squanto had escaped and made his way to London, from where he returned to America as a scout for the Newfoundland Company. When he finally reached his old home, he found it abandoned—the result of a plague that had decimated the coastal population of southeastern New England. He, too, spoke English, and became the little colony’s translator, as well as its instructor in planting corn and finding local resources. That same day, the “great Sagamore” Massasoit arrived with his retinue of sixty men and, with the help of the English-speaking Native men, entered into a treaty of peace with the colonists that would last more than fifty years.

The following autumn, the all-important corn harvest that would insure Plymouth Colony’s survival proved successful, although some of the English crops were a disappointment. In honor of this 1621 harvest, Edward Winslow noted that Governor William Bradford sent four men out to hunt wildfowl “so that we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors.” They brought back enough fowl to feed the community a week, including “many of the Indians [who came] amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men.” They hosted their guests for three days of feasting, to which the Indians contributed five deer. This ecumenical outdoor harvest feast and November celebration was America’s “First Thanksgiving; ” it was later adopted by other New England colonies in memory of that momentous event.

The holiday remaind a regional observance until 1789 when George Washington declared the first nation-wide Thanksgiving for the new United States (an earlier Thanksgiving for the thirteen colonies had been declared by the Continental Congress in 1777). The custom of national Thanksgivings lapsed after 1815, until Abraham Lincoln, urged on by Sarah Josepha Hale (editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book and a fervent advocate for a national Thanksgiving holiday), declared a traditional November Thanksgiving in 1863. Since that time, the holiday the Pilgrims established has been celebrated without fail each fall, and the memory of that First Thanksgiving has been indelibly colored by the famous images of colonists and Native neighbors sitting down to dine in autumnal splendor, surrounded with the bounty of the harvest.

This is the basic Thanksgiving story as most of us remember it from grade school. But although at least partially accurate, it only represents the tip of the iceberg when it comes to what Thanksgiving means to us today.

Where I come from, Thanksgiving is an unavoidable fact of life. Despite (or perhaps because of) growing up in Plymouth, Massachusetts, many young Plymoutheans such as me never gave the history of the Thanksgiving holiday much thought. Tradition asserted that the holiday originated there with the Pilgrims and their Indian neighbors, and that was that. We engaged in the same family gatherings and time-honored Thanksgiving turkey dinners as other Americans. The ubiquitous, mass-produced images of buckle-hatted Pilgrims, generic Indians, turkeys, pumpkins, and cornstalks that hung in Plymouth classrooms were the same as those found in schools and homes across the nation. Like school-children throughout America we accepted this as gospel, and besides, it lent the historically famous, declining industrial town we lived in a touch of glamour each autumn. The Pilgrims were, or had been, real enough—it was only later that this crowning glory was seen to be, like the town itself, more modest in reality.

Of course, there was considerable fuss made about the holiday each year in “the town where Thanksgiving began,” but it was more for the accommodation of holiday visitors than for us townsfolk. Older Plymoutheans have fond memories of the holiday morning circuit they made as youngsters to take advantage of the free cider and donuts provided by the town for distribution to the public at the historic houses. We participated in the annual Pilgrim Progress march to the windy eminence of Burial Hill on gray November afternoons, posed in tableaux illustrating the Pilgrim Story on the stage of Memorial Hall, and on occasion distributed free “Pilgrim hats” at Pilgrim Hall Museum when official Plymouth made an extra effort to gratify holiday guests. Yet most Plymoutheans were reluctant to interrupt their private holiday arrangements to attend to the needs of tourists, and avoided the downtown area on Thanksgiving, despite efforts to involve them in the new public interfaith service in First Church. While we had our dinner at home or with grandparents, a few specially designated local restaurants served endless turkey dinners to crowds of eager visitors, and the Town of Plymouth even hosted a Thanksgiving feast in Memorial Hall. Such holiday activities were a grudgingly acknowledged part of life in the Old Colony town.

After Plimoth Plantation opened the Pilgrim Village in 1958, its annual Thanksgiving observation became the central attraction for modern pilgrims seeking the “First Thanksgiving” spirit. Plimoth Plantation, the new, open-air re-creation of the original Pilgrim settlement, was the largest and most popular Pilgrim attraction in town. As Thanksgiving was the ultimate Pilgrim event, the holiday became the museum’s climactic close of the tourist season. Pilgrim Progresses were still put on each year, but the mulled cider, tableaux, free hats, and other public accommodations faded away. An “authoritative” version of the traditional story intended for schools was included in Plymouth Colony: The First Year, a film made at Plimoth Plantation in 1962. It faithfully re-created the standard scenes of outdoor cooking, the arrival of the “Indians” (high school boys in loincloths and body makeup, carrying a taxidermized deer), and the famous dinner after the manner of popular illustrations in children’s books with an odd, picturesque admixture of raw and cooked foods. I worked for the Plantation aboard the museum’s Mayflower II during undergraduate summers and off-season weekends from 1963 to 1966, but the ship was on the downtown Plymouth waterfront several miles away from the Pilgrim Village. I missed the gala Pilgrim Village celebrations, but the importance of the conventional Thanksgiving story for the museum was inescapable.

When I returned to Plimoth Plantation as its research librarian in 1975, I found that the institutional engagement with Thanksgiving had undergone a revolution. The years between my summer employment and my return wrought drastic changes throughout American society, and Plimoth Plantation had been deeply involved in the intellectual turbulence of the times. The old verities of the Pilgrim story had been attacked by a new cohort of museum professionals eager to debunk the cozy sentiments of the preceding generation. The museum’s earlier Thanksgiving observation had been arraigned on two counts—the false identification the 1621 celebration as a Puritan day of thanksgiving and praise, and its negative symbolic significance for modern Native Americans.

The Plantation had always recognized that the famous “First Thanksgiving” was not quite a true Calvinist Thanksgiving. An authentic New England Thanksgiving was an officially declared weekday event marked by a day of religious meetings and pious gratitude for God’s favorable providence (and celebratory dinners as well). The 1621 festivities, on the other hand, with their recreations, heathen guests, three-day duration, and no mention of church far more closely resembled a secular English harvest celebration. However, this anomaly had always been considered insignificant in the face of the 1621 event’s traditional identification as the fons et origo of our modern holiday.

Such equivocation became unacceptable in the late 1960s. Not only was the 1621 event determinedly redefined as a secular harvest festival, but also its public observance at the Plantation was shifted from November to Columbus Day weekend in 1973, closer to the Michaelmas (September 29) season when such events had been traditionally held in England. Special Thanksgiving Day activities were abolished and the day itself was given over to unexceptional seasonal work demonstrating November preparations for winter. It was in many ways a daring decision to reinterpret the history of the holiday, as it might well have had a drastic effect on the Plantation’s critical Thanksgiving Day attendance. The change did upset some traditionalists, but most visitors continued to flock to the Pilgrim Village on the holiday as they always had. In fact, the new Columbus Day “Harvest Festival” became a popular tradition in its own right, so that there were two revenue-maximizing events where before there had been only one.

Another influence on the Plantation’s reinterpretation of Thanksgiving was the Native American protests that came to surround the Thanksgiving holiday. Thanksgiving is the only American holiday in which the American Indian has been accorded a substantial if supporting role, but the image of the Plymouth colonists and their Wampanoag neighbors sitting down to a feast in irenic harmony on a golden autumn afternoon was not one some Native peoples felt comfortable with. This sentimental impression of the “First Thanksgiving” was protested in Boston and Plymouth on Thanksgiving in 1969 by a group of American Indian students, not so much for its historical inaccuracy—the events had actually occurred more or less in the manner commonly described—but in recognition that the pretty picture obscured later momentous conflicts between the Indians and the English colonists.

The following year, on the 350th anniversary of the landing at Plymouth, the committee in charge of the anniversary celebration withdrew an invitation to Frank James, a Wampanoag teacher from Cape Cod, who had planned to deliver a thoughtful but critical dissent to the general congratulatory tenor of the anniversary celebration. In response Mr. James organized a protest on Thanksgiving, 1970, which attracted sympathizers from numerous Native communities, including members of the radical American Indian Movement, freshly energized by the recent occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. In the spirit of the times, the protest included various melodramatic scenes such as an assault on Mayflower II during which the English flag was torn down, the manikin representing the Pilgrim ship’s master thrown into the harbor, and nearby Plymouth Rock “buried” with sand. Plimoth Plantation invited the Native Americans to a turkey dinner, but on arrival the protesters overturned the tables and bore away the cooked turkeys. The protest, called “the Day of Mourning,” was subsequently institutionalized by the United American Indians of New England as an annual event. A new Thanksgiving tradition was born.

The refusal of the protesters to accept the Plantation’s hospitality only heightened the museum’s desire to reach out to the Native community. A quasi-independent “Indian Program” was established in 1973 that employed Native individuals in the new “Summer Camp” exhibit, and respected local leaders in the Wampanoag community were asked to become advisers to the program. It was impossible in light of these changes to continue with the old Thanksgiving festivities, and the shift in interpretation to a “harvest festival” was accordingly instituted. A press release was issued to explain this change, outlining the historical justification for the radical revision of the program in 1973.

This press release was the one I was given so that I might answer public inquiries about the Thanksgiving holiday, a time-consuming responsibility that fell to the Research Department each autumn. The points made in the release seemed compelling, although I thought one or two small corrections might be made. For example, the release stated that the first national Thanksgiving had been declared by Washington in 1789, but this overlooked the Thanksgiving declared by the Continental Congress in 1777. Plimoth Plantation was ready to relinquish the title for 1621 (if not 1623), but it was opposed to other, even less-credible, “first thanksgiving” claims. It seemed a small point to us, but the question of “the true first Thanksgiving” seemed to loom large in the public mind, and there were a number of rival claimants to the title. The media were similarly fascinated and eagerly sought out these claims to earlier Thanksgivings in order to challenge Plymouth—whether or not any had any real historical significance.

There were, we found, numerous pretenders to the title of the “First Thanksgiving.” For example, Dr. Michael Gannon of the University of Florida cited a thanksgiving service held for Ponce de León’s expedition on April 3, 1513. The Texas Society of the Daughters of the American Colonies had erected a marker on the Palo Duro commemorating an alleged thanksgiving proclaimed by Fr. Juan de Padilla for Coronado’s troops on May 23, 1541. Similar examples had been extracted from historical records for 1564 (Florida), 1565 (Florida), 1578 (Newfoundland), 1598 (Texas), 1607 (Virginia), 1607 (Maine), 1610 (Virginia), and 1619 (Virginia). Each was technically a “thanksgiving,” and each occurred before Plymouth Colony was founded in 1620, but these claims were essentially irrelevant, as each was an isolated instance that had no connection with, or influence on, the future American holiday.

The alternative “firsts” were usually instances from the Catholic or Anglican liturgical tradition giving special thanks to God for some act of providence, during a Sunday mass or service rather than a separate day set aside in the Calvinist manner. They might also have been thanksgiving services celebrated on the day of a safe arrival, such as Adelantado Menéndez De Avilés’ arrival in Florida on Saturday, September 8, 1565, or Captain John Woodleaf’s arrival at the Berkeley Plantation on Saturday, December 4, 1619. Neither the Menéndez event, which even included a dinner for members of the local Seloy tribe, nor the Berkeley service, which was supposed to be held each anniversary of the arrival that day in Virginia, were Sabbath-day events. Moreover, the one-shot Florida service was of little interest to historians of early America, and the Berkeley tradition was stillborn due to the massacre of the colonists in 1622. The existence of this purported annual thanksgiving had been forgotten until rediscovered by Virginia partisan Lyon G. Tyler in 1931.2 In 1958, John J. Wicker, Jr., established the “Virginia Thanksgiving Festival” for the first Sunday in November.

Historically, none of these had any influence over the evolution of our modern holiday. The American holiday’s true origin was the New England Calvinist Thanksgiving. Never coupled with a Sabbath meeting, the Puritan observances were special days set aside during the week for thanksgiving and praise in response to God’s providence. Not surprisingly, the glamour of chronological precedence—evidence of a deep-rooted “Guinness Book of World Records” mind-set among the public—overshadowed the question of historical significance, and we were obliged to respond to such claims every year.

My associate Carolyn Freeman Travers and I revised the press release and incorporated it in The Thanksgiving Primer, a booklet that included more information on Thanksgiving, the Pilgrims, their church services, cuisine, dress and myths associated with their popular image. I supplied an analysis of the probable origins of the modern holiday, observing that it appeared to be a synthesis of three independent traditions: the Calvinist day of Thanksgiving, the customary harvest festival and Forefathers’ Day, an earlier holiday celebrating the Pilgrims’ landing on Plymouth Rock on December 22 whose observation had faded away when Thanksgiving monopolized the Pilgrim story after 1900.3

Despite our efforts, the conventional misconceptions and popular stereotypes associated with Thanksgiving continued unabated among the general public. Americans still learned about the Pilgrims and Thanksgiving in grade school where traditional images and stories were uncritically accepted—or if they were questioned, it was often only to favor the Indians over the Pilgrims, with the basic 1621 narrative modified to suit. Most adults felt that Thanksgiving history was for kids, and not worth serious consideration. Consequently, almost all available books on the subject were— (and still are—) aimed at children. When they concentrated on the colorful 1621 event, some authors conscientiously adopted the Plantation’s strictures on period costume, foodways, activities and Native involvement, always with the popular conviction that Thanksgiving began with the Plymouth harvest festival. The few scholarly works on the subject such as William De Loss Love’s Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England (1895), the Lintons’ We Gather Together (1949), and Appelbaum’s Thanksgiving (1984) accepted the modern importance accorded Plymouth and harvest observances, although De Loss Love did so somewhat diffidently in the face of his own evidence.4

The first doubts I had about the common assumption that there was an unbroken linear tradition between the Pilgrims’ harvest festival and the modern Thanksgiving holiday occurred in 1985 during Plimoth Plantation’s mounting of Aye, Call It Holy Ground, an exhibit on the popular Victorian images of the Pilgrims. We had no trouble finding Victorian visual representations of the voyage of the Mayflower, the landing on Plymouth Rock, the “courtship of Miles Standish” and similar tropes, but we were unable to locate a suitable nineteenth-century painting, or even a big Harper’s Weekly engraving illustrating the famous “First Thanksgiving” in all its familiar outdoor autumnal splendor. The best-known depictions by Jennie Brownescombe (figure 1), J. L. G. Ferris, and Percy Moran all dated to after 1900. The closest we got at the time was a Harper’s engraving from 1870 depicting the Pilgrims gathered indoors around a table with Indian guests standing grimly behind them, which was not quite the depiction we had in mind. There was another early “Pilgrim and Indian” Thanksgiving image in addition to the Harper’s print that we did not discover until much later. Plimoth Plantation curator Karin Goldstein located The First Thanksgiving, a painting by Edwin White (1817 – 1877) that appears to be earlier than the Harper’s engraving, but it does not seem to ever have been published or reproduced and therefore had no particular cultural influence. The White Thanksgiving has a Pilgrim family seated indoors with a single Indian standing behind them, more like a silent butler than a guest.

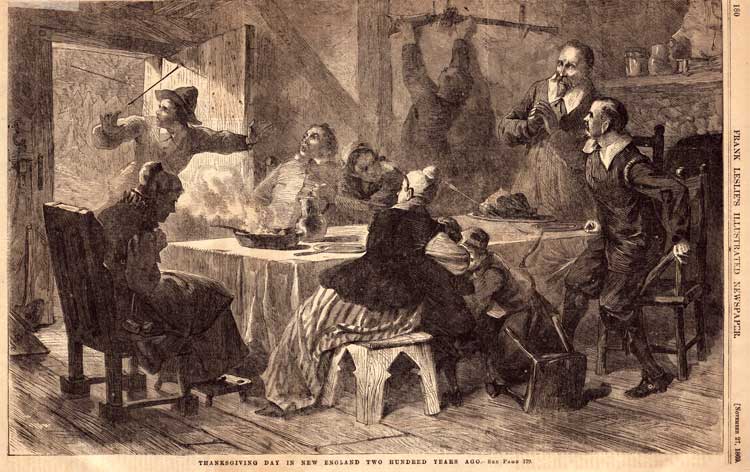

I was surprised, not only by the absence of the very famous outdoor autumn scene in Victorian art, but also by an unexpectedly popular trope of violence between the colonists and the Indians, which appeared to be a common theme in nineteenth-century depictions of colonial Thanksgivings—quite in contrast to irenic representations of the 1621 dinner. An early example of these violent images, which appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated (1869), was entitled Thanksgiving Day in New England Two Hundred Years Ago. It showed a Puritan family’s Thanksgiving dinner interrupted by a hail of arrows from an unseen enemy. Other examples involving generic Puritan-era colonists and hostile Indians ranged in quality from full-page engravings in Harper’s and Leslie’s to humorous and irreverent cartoons in the old Life magazine (1883 – 1936). The hail of arrows from an invisible adversary was a recurrent theme, there even being examples by Norman Rockwell showing a fleeing boy carrying a turkey or a bewildered Pilgrim huntsman amid arrows from off-stage. This convention of colonial violence appeared to have been far more resonant in the nineteenth century than the peaceful Thanksgiving gatherings of the Brownescombe variety. Presumably the contemporary frontier wars following the Civil War had made it difficult for Victorian artists and their audience to relate to any historical image of peaceful relations between the colonists and their Indian neighbors. The now-familiar outdoor dinners significantly appeared only after the overt violence out west was over. Also, few images specifically referenced the 1621 Plymouth event at all, which seemed odd. One of the few identifiable “Pilgrim” (as opposed to generic colonial) representations from this period presented a contest between a Pilgrim musketeer and an Indian bowman in Harper’s Weekly (1894). They were shooting at a target made up of a stuffed scarecrow with colonial shirt and breeches, hardly the peaceful aspect celebrated in later art.

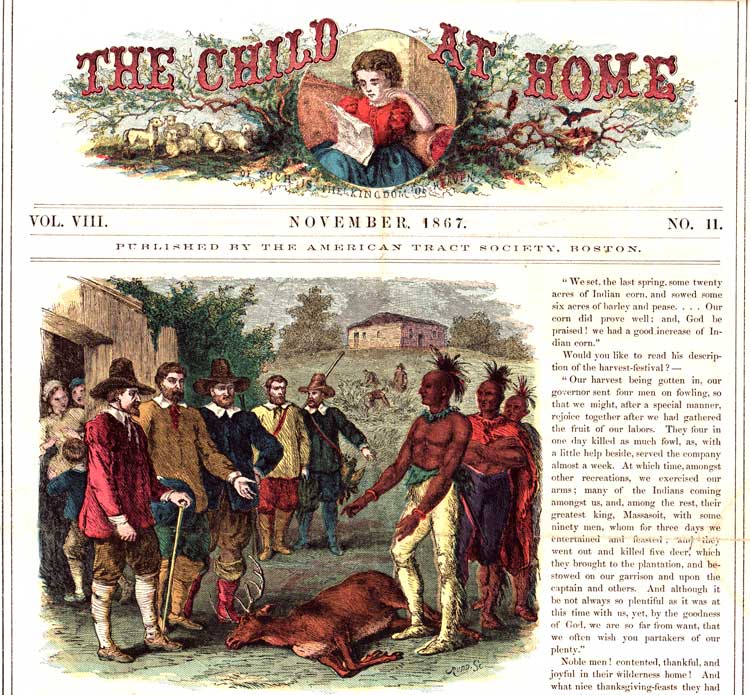

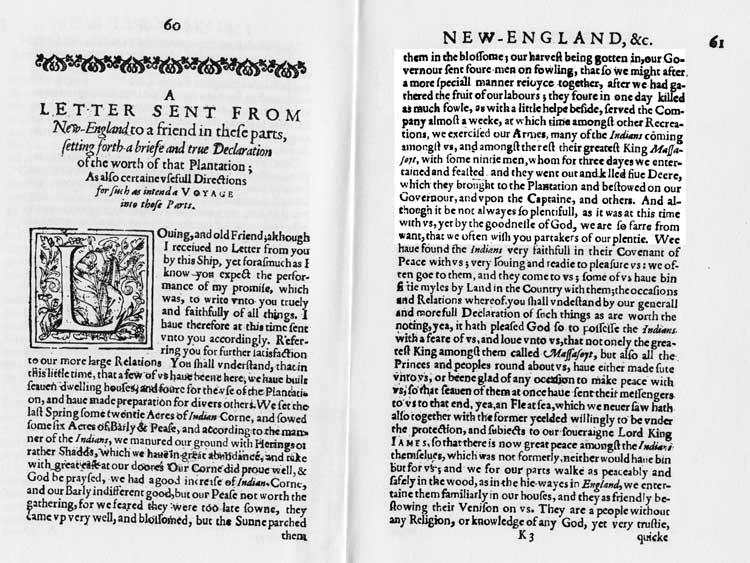

Since the description of the famous 1621 harvest by Edward Winslow in Mourt’s Relation—from which the modern conception of the holiday is drawn—was first published in 1622, it was surprising that the nineteenth-century artists would ignore the peaceful implications of the passage that so impressed their successors:

Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors. They four in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the company almost a week. At which time, among other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed upon our governor, and upon the captain, and others. And although it be not always so plentiful as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.5

I undertook a search in early sources to see just when the current emphasis had begun, and found that no account of the Pilgrims published before the 1840s made any reference to either a Thanksgiving or a harvest celebration in 1621. Eventually I discovered why this was the case. Although Mourt’s Relation had been published in 1622, the original booklet had, not surprisingly, become rare, so that by the eighteenth century there were apparently no surviving copies in New England. Scholars relied on an abridged version included in Samuel Purchas’ Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes (1625), which was reprinted by the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1802.6 The Purchas version omitted the Winslow letter, so the 1621 event had been entirely forgotten! It was not until a copy of the original pamphlet was discovered in Philadelphia in 1820 that the famous harvest account was rediscovered. The previously missing information had no immediate effect, presumably because the Massachusetts Historical Society, rather than printing the text in full in 1822, extracted the missing phrases and paragraphs and arranged them with directions as to where they could be inserted into the abridged Purchas version, a singularly awkward manner of proceeding.

The first republication of the full text of Mourt’s Relation appeared in 1841 in Rev. Alexander Young’s Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers.7 Significantly, Young added a footnote to the description of the 1621 event stating, “This was the first Thanksgiving, the harvest festival of New England.” This is the earliest identification of the 1621 event as a Thanksgiving. The 1621 festival may have been nothing like a Puritan Thanksgiving, but by the time Young wrote, the New England holiday had lost much of its old Puritan providential significance. Apparently the 1621 event looked very much like a contemporary Thanksgiving to the liberal Unitarian clergyman, hence the identification. Young’s judgment that the Pilgrim celebration and harvest was the “first Thanksgiving … of New England” was slow to attract public attention, despite the support of Dr. George B. Cheever in his edition of the Mourt’s Relation text published in 1848. After all, the Thanksgiving holiday had developed a substantial historical tradition quite independent of the Pilgrims, emphasizing contemporary New England family reunions, dinners, balls, pumpkins, and turkeys. Early winter scenes rather than harvest motifs dominated Thanksgiving imagery, as in the sleigh ride “over the river and through the wood” in Lydia Maria Child’s poem (1844) or the popular Currier and Ives lithographic winter scene of George Durrie’s Home for Thanksgiving (1867). In fact, rather than being the autumnal icons they are today, the Pilgrims themselves were most often depicted in snowy landscapes because of their arrival in Plymouth Harbor in the winter of 1620, which was associated with the then widely-observed holiday of Forefathers’ Day commemorating the annual anniversary of the landing at Plymouth Rock on December 22. Having solved the mystery of the “missing link” between the 1621 event and the modern holiday, the challenge was to discover how the American Thanksgiving holiday actually evolved over the intervening centuries. What was the true history of America’s Thanksgiving Day?

1. Henry Cabot Lodge. The Democracy of the Constitution and Other Addresses and Essays. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1915, pp. 208-209.

2. Michael Kammen. Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture. New York: Knopf, 1991, p. 386.

3. I wish now I had never done so. After I concluded that Forefathers’ Day was historically unrelated to the evolution of Thanksgiving, I was never able to convince some of my colleagues of the fact, and my initial assumption kept coming back to haunt me. People tend to absorb information once and are loath to change their familiar views.

4. There have been recent exceptions to this assumption, in particular Elizabeth Pleck’s excellent chapter “Family, Feast and Football” in Celebrating the Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000, pp. 21-42, and Janet Siskind, “The Invention of Thanksgiving: A Ritual of American Nationality,” Critique of Anthropology 12 (1992). I should mention that I talked to Ms Siskind at length about my discovery and its ramifications while she was researching the article.

5. A Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth. Dwight B. Heath, ed. New York: Corinth Books, 1963, p. 60-61