A Wilderness Tamed:

The Story of Freeport, Grand Bahama

A Wilderness Tamed:

Part I - Grand Bahama Before Freeport

A Wilderness Tamed:

Part II - Wallace Groves and the Abaco Lumber Company

A Wilderness Tamed III – Freeport Begins 1955-1960

A Wilderness Tamed III – Freeport Begins 1955-1960

A Wilderness Tamed IV – Freeport The Developing Years 1960-1965

A Wilderness Tamed IV – Freeport The Developing Years 1960-1965

A Wilderness Tamed V – Freeport The Vintage Years 1965-1970

A Wilderness Tamed V – Freeport The Vintage Years 1965-1970

A Wilderness Tamed VI – Freeport Comes of Age 1970-1986

A Wilderness Tamed VI – Freeport Comes of Age 1970-1986

![]()

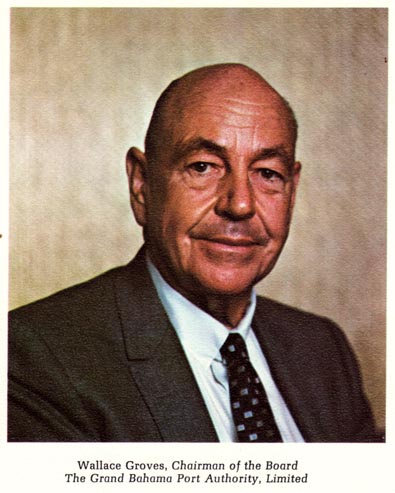

The 1960 Agreement broadened the focus of the Port Authority from Groves’ original concentration on industrial development to include development of a resort and residential sector on the newly-acquired property. New investment in infrastructure called for both massive additional funding and the recruitment of men and companies capable of realizing the potential of the Lucaya property. It was at this point that the Allens introduced a successful if notorious developer of communities in Florida, the Canadian promoter Louis A. Chesler. Chelser had made his fortune in Canadian uranium mining stocks before moving his operations to Florida where his General Development Company constructed developments at Port Charlotte, Port Malabar, and Port St. Lucie, in what could serve as a model for Grand Bahama. He was also heavily involved in the motion picture production and distribution business, being the chairman of Seven Arts, a company that bought the rights to various old movies and cartoons. Chesler and his partners had bought a controlling interest in Seven Arts and engineered the purchase of the Warner Brothers pre-1948 film library in 1956.

A new corporation, the Grand Bahama Development Company (or DEVCO), was created in the fall of 1961 to undertake the task of building new hotels and housing developments. Chesler brought $12 million to the table by pressing Seven Arts into investing $5 million in DEVCO, with another $5 million extracted from Loredo Mines, plus a loan secured through a New York bank (the actual cash coming indirectly from Seven Arts). Half of the DEVCO stock was issued to the Port Authority, with Seven Arts (Bahamas) and Loredo Uranium Mines receiving 20.75% each. Lou Chesler personally acquired 8.5%, and was appointed chairman of the company. For this investment, the new corporation received 102,305 acres of Port Authority land that in time became “Lucaya”.

Although such investment was essential for the development of “the New World Riviera”, Chesler was the very sort of investor that Groves had purposefully steered clear of earlier – a bombastic promoter “with suitcases full on money” who was more interested in speculation and land sales than in careful community growth. The two men did not hit it off – it being said at the time that their personalities met like oil and water. As Mrs. Groves noted, it had been her husband’s intent (once he accepted the necessity of furthering tourism and residential construction) “to build a creatively designed community which would be cosmopolitan, yet one which would reflect the pleasant, relaxed atmosphere characteristic of all of the Bahamas.” Chesler, on the other hand, wanted the big bucks that an elegant and enormous resort like Palm Springs, California could bring, and sought to sell property to opportunist speculators more than to the solid citizens who would have a long term interest in Freeport that Groves preferred. The first order of business, however, was the construction of the 200-plus room hotel required for the 1960 Supplementary Agreement by the end of 1963. This goal was pursued with vigor, in the construction of the $8 million Lucayan Beach Hotel – a project that would result in headaches for all involved.

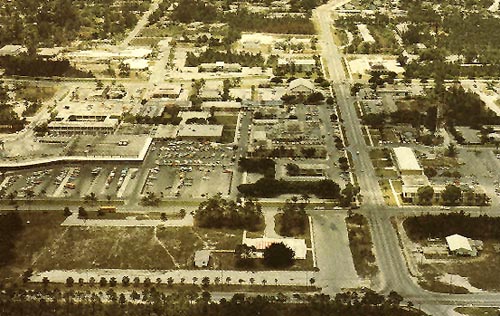

Downtown FreeportIn the meantime, Freeport continued to expand exponentially. As Mrs. Groves recalled, “almost overnight, Freeport took on the appearance of a gigantic construction camp”. In 1962, D. K. Ludwig resurfaced and began planning an immense project on land he owned south of downtown Freeport that included two new hotels (the King’s Inn and the Xanadu Beach Resort) with a 1,500-home housing development (Bahamia) and a championship golf course in between. He signed an agreement with the Port Authority in late 1963 to begin work on his grand project; with the 300-room King’s Inn opening on January 26, 1965 (the Xanadu was built in 1968). The concept of an international shopping center, proposed earlier as “Hong Kong West” but never begun, was revived as the “Crossroads of the World” – later becoming the International Bazaar, work on which began in 1965.

The cultural character of the community was enhanced by the founding of such amenities as the Freeport Players Guild by Jack Hayward, a Sports and Social Club for full-time employees (of all races) of the Port Authority licensees, and a Garden Club dedicated to making Freeport beautiful. Although the sight of society women digging in the dirt to plant decorative shrubs and flowers puzzled older inhabitants, the Garden Club was able to make considerable progress in making the bare limestone landscape blossom with plantings provided by Walter Rose at the Lucayan Nursery. Freeport residents organized local branches of the Rotary and Kiwanis service club, the former in January, 1962. A new Freeport High School was built and the old building turned over to the Methodist Church, and the Christ the King Anglican Church was consecrated.

Hayward was also responsible for adding another cultural feature to Freeport – a touch of Colonial Anglophilia that greatly appealed to upper class visitors visiting the island. He imported a classic red double-decker London Routemaster bus (and a black London cab that he drove around in), and a few standard British phone booths. Other English touches included the faux-Tudor Pub on the Mall, the Britannia Pub and the massive bronze head of Winston Churchill in Churchill Square. A police station was built and manned by 18 Bahamian officers. Although crime figures in Freeport were low, they had increased in the local Bahamian communities.

New businesses opened, including the Todhunter-Mitchell distillery and soft drink bottling company, the Freeport Trading Company that provisioned visiting ships and supplied local retailers with goods and in 1965, a Winn Dixie market. The $50,000,000 Bahama Cement Company was officially opened by Bahamian Premier Sir Roland Symonette on March 15, 1964. Other resort hotels included the downtown Freeport Inn, while construction began on the grand 614-room Holiday Inn in Lucaya and the 168-room Oceanus Inn on Bell Channel Cay.

Despite the best initial efforts of DEVCO, however, the development of Lucaya was still not happening quickly enough. Land sales remained sluggish and funding was running low. This resulted in the radical decision to secure capital through the in

troduction of casino gambling. Gambling had been illegal in the Bahamas since 1901, but a couple of small casinos on Cat Cay south of Bimini and in Nassau had been made legal in 1939 through an act (sponsored by Stafford Sands) that allowed the Bahamian Governor in Council to make exemptions to the law. A new company, Bahamas Amusements Ltd., was incorporated on March 20, 1963. Shares in the Amusements Company were divided between Chesler and Mrs. Groves, who each received 498 shares of 500 Class 1 shares and 498 Class 2 shares. The remaining Class 1 shares went to two of Chesler’s Canadian partners, while the two Class 2 shares went to Keith Gonsalves (future director of DEVCO and of Bahamian Amusements, Ltd.), and Sir Charles Hayward, another DEVCO director. That same day, the new company made an application, drafted by Stafford Sands, for a Certificate of Exemption to the Governor in Council, in great secrecy. The certificate was quietly granted without difficulty eleven day later on April 1, 1963, allowing the Amusements Company to operate an unlimited number of casinos on Grand Bahama for a period of ten years. Groves stipulated that all of the profits from Bahamas Amusements were to go to DEVCO to support the island’s hotels, as well as subsidizing land sale advertising, Bahamas Airways flights to Grand Bahama and the encouragement of cruise ships to visit Freeport.

As always, the Certificate of Exemption came with conditions. It would be cancelled if within three years the Port Authority had not added at least 300 hotel rooms in addition to those already existing or under construction, and another 400 rooms had to be added within five years. Also the management and control of all casinos had to be maintained by Bahamas Amusements, and not transferred to any other corporation or individual. It was further stipulated that no US citizens be allowed to work in the casino (through fear of mob involvement), and gambling was forbidden to Bahamian residents. It also allowed for the taxation of the casino profits.

The idea of a casino had been under consideration for some time, presumably at the suggestion of Louis Chesler and Stafford Sands. Wallace Groves only came to grudgingly agree to in 1961 when there seemed to be no other solution to the development crisis. Chesler was personally not only a financial speculator but also an enthusiastic gambler. He had long been involved with casinos (and the inevitable organized crime figures), being instrumental in financing the purchase of the 450-room Hotel Nacional casino in Havana for Mike McLaney in 1958 before the latter moved to the Bahamas to manage the Cat Cay Club.

Sands had decided that it was wiser to wait until after the 1962 Bahamian election to make a bid for exemption. The plans for the Lucayan Beach Hotel included an area designated as a “handball court”. Once the Certificate of Exemption had been issued, it became the Monte Carlo Room, a 76 x 120-foot opulent casino with an enormous crystal chandelier and a carpet with three-inch pile. It was separate from the rest of the hotel (both physically and legally), which was equally sumptuous, having cost Chesler’s construction firm $25,000 per room. The Monte Carlo casino opened on January 11, 1964.

The costly luxurious appointments of the hotel and casino were not in themselves an extravagance – they were calculated as appropriate for attracting the wealthy “high-roller” gamblers whose losses could make or break the operation. These people were carefully recruited in the US and elsewhere and flown to Freeport on all-expense-paid “junkets” that cost the casino a great deal, but also guaranteed its profitability. As Life Magazine reported in February, 1967, “In 1965, its first full year of operation, the Lucayan Beach Hotel casino on Grand Bahama spent $494,552 on chartered flights, just to bring in freeloading planeloads of ‘high-rollers’— big-spending gamblers with blue-chip credit ratings-who had been invited from all over the U.S. Another $935,268 was allocated to provide hotel and ship accommodations for such pampered guests.” The junkets were very successful, as DEVCO officer Keith Gonsalves noted, bringing in two-thirds of the casino’s profit.

The Monte Carlo’s success proved to be the turning point in DEVCO’s financial situation. Funds from Bahamas Amusements were able to underwrite the Lucayan development for several years. Unfortunately, the Lucayan Beach Hotel, which had been sold to Allen S. Manus, a Canadian rival of Chesler’s, was not equally successful, going into receivership in 1966 and eventually leading to the bankruptcy of the Canadian holding company of the Atlantic Acceptance Corporation. Ltd. It also resulted in the embarrassing scandal of Bahamian government corruption and Mafia influence that would erupt in the media in 1966 and 1967.

(An Interview with Wallace Groves, 1980)In the meantime, the financial shenanigans and intemperate behavior of Louis Chesler brought the tension between him and Wallace Groves to a breaking point. Chesler first offered to buy out the Groves’ interest, but Groves was able to acquire enough stock to gain full control of DEVCO and Chesler found himself replaced as director by banker Keith Gonsalves in May, 1964, and was cut out of Bahamas Amusements as well. Freeport/Lucaya was now poised to enter in what would prove to be its hey-day of growth and prosperity. The 1965 Bahamas Handbook reported that:

1965 was a miracle year in Freeport. Everything increased or expanded over 1963: roads from 103 to 137 miles; shops and stores from 27 to 113; Freeport School from 160 to 375 pupils; motor vehicles from 1,646 to 4,221; and gasoline consumption from 111,382 (U.S.) gallons in December of 1963 to 234,273 in December, 1964. The overall population of Grand Bahama, 8,454 in the census of 1963 (compared with the 4,095 of 1953), was estimated at the end of 1964 to total 13,000. Of these, 4,700 were residents of Freeport/Lucaya – an increase not of twice but almost thrice over the previous year … The total of business licences granted by the Port Authority rose to 401 by the end of 1964, compared with 244 in 1963. (p. 326)

As Mrs. Groves later recalled, “Suddenly, the city was viewed as a get rich quick place, rather than a ‘go broke place’ as had been thought by many islanders in past years … It was considered a vacationer’s and a businessman’s utopia. Tourists flocked in droves to the isalnd anxious to hobnob with the celebities who had made the Lucayan Beach their playgorund. Proposals of every sort of business imaginable flooded the Port Authority’s desks. Land sales skyrocketed!”.

The construction of new hotels couldn’t keep up with the demand for rooms, so the cruise ship Italia was brought to Freeport Harbor to serve as a floating hotel under its new name, the Imperial Bahama. The airport quadrupled in size and a jet landing strip was made available. The Underwater Explorers’ Club was formed on the Bell Channel and attracted serious divers from around the world who wished to take advantage of Grand Bahama’s crystal clear sediment-free waters. The Holiday Inn opened for business, construction began of its new towering fourteen-story Ocean House neighbor on the Lucayan Beach, as did work on the International Bazaar and the El Casino complex near to Ludwig’s King’s Inn. Groves’ dream had finally come to fruition!